One of the first things you learn as a child of immigrants is that your life and your story are never really your own. Your existence is tied to generations of sacrifice and suffering that have brought you here, to the present day, and your duty as a descendant of these generations of sacrifice is to exist as one part of a whole. The success of your family is predicated on how well you contribute to this nexus of identities, and to ask for any sort of exemption is laughable at best, selfish at worst.

Being part of a bigger community is a truth I've internalized since before memory, but I struggled with it a lot at an early age. My favorite question as a kid was, "But why?"--a question my parents didn't always have a ready answer to. "One of you kids will have to be pre-med." But why? "It's not seemly for a girl to play the drums." But why? "Yes, you have to wear a dress to the recital." But why?

Independence was considered an American value, and my parents, immigrants from Taiwan, were more concerned about the ripple effect of our actions on the extended family than about encouraging their daughter to go her own way. (Years later, I would come to understand that their decisions were driven by equal parts self-preservation and fear.) Carving out an identity independent of my parents and my culture, then, often felt like an impossibility. Those cultural roots run deep.

[Claudia's] just like me! I'd think. Only, like the secret me I keep hidden on the inside.

My first language was Mandarin, spoken at home by my parents; English entered my repertoire around the time I started preschool and soon became my primary language, the one in which I began to nurture my burgeoning love for plot, character, and narrative.

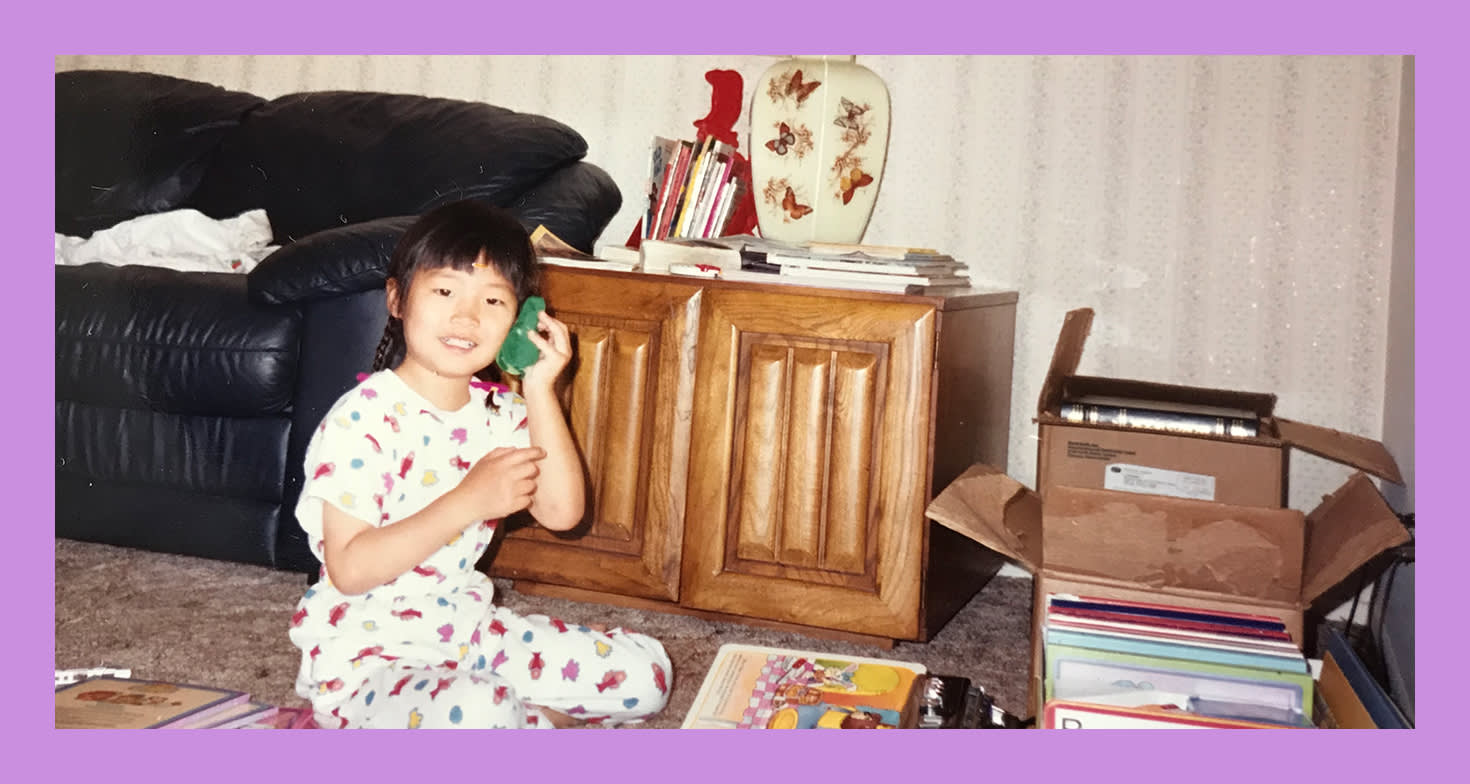

I fell in love with it all. The words, the stories, the ways that I could access new worlds and perspectives through books. By the time I was a seven year old in thick lenses, I saw reading as an escape, a declaration of agency; books helped me step outside of my everyday experiences and into entire worlds of imagination that felt, at the time, like they were uniquely my own.

Books were how I began to understand independence.

And so was writing. I started writing and illustrating at a young age, convinced a life of literary greatness awaited me. I remember writing a story about a family of mice who lived in the walls of a human home, eavesdropping on their drama and fashioning tiny furniture from their scraps. My dream job was to be an author with a capital "A," the sort who was called upon to read their own books aloud during elementary school story time. Roald Dahl was my hero. This was my ambition.

I remember the first time I felt like this lofty goal was actually a possibility. I'd started reading The Baby-Sitters Club books in the second grade, because all the popular girls in class were reading them and I desperately wanted to fit in. As a naturally shy second grader, I wanted to show that I was hip and with it, too, and part of that was keeping up with what the cool kids were doing so I could participate in their loud conversations at lunchtime.

"Even as a kid, I just remember being like, Claudia's different because she's not a nerd." --Ali Ahn

It helped that Claudia Kishi, the only Asian American character in the books, was cool and hip in ways that I wasn't, but that I imagined I could be just by association. She had a mean sense of style, loved art, and hid loads of junk food from her parents. Her devil-may-care attitude was so unlike how I'd been brought up--anxious about homework assignments, practicing piano daily, catering to my parents' wishes--that reading about her felt like a kind of catharsis. She's just like me! I'd think. Only, like the secret me I keep hidden on the inside.

On the surface, I was quiet, shy, and obedient; my teachers often told my parents I was great at following directions, but terrible about speaking up in class. But I knew the truth, and Claudia's character helped me realize it: I wasn't actually shy, just an artist who was misunderstood. Overlooked. It was my superpower, this creative streak, and I held onto it like a secret folded note in my pocket, a shield of invincibility that I would wield whenever teachers told me that I had so much potential, if only I weren't so shy. Ha, I'd think. If only they knew.

~

Ali Ahn, who voices the Claudia Kishi stories in the new Baby-Sitters Club audiobook series, had a similar experience growing up in Los Angeles, raised by her Korean immigrant parents. She, too, understood early on that her story was not wholly her own. For instance, though she discovered a love for acting in elementary school, Ahn remembers viewing the performing arts as a hobby rather than an actual profession--a way of seeing she now attributes to her parents.

"I think my parents' immigrant experience, coupled with a lack of representation, really did something," she tells me. "When your parents don't see any examples of people who look like you pursuing the careers you want to, it makes sense why they don't want you to pursue the arts. And you start to assume [the possibility] doesn't exist because you don't see any role models doing what you want to do."

Ahn found that reading The Baby-Sitters Club series as a kid became a small but significant act of rebellion; in the same way that Claudia hides her beloved Nancy Drew mysteries from her strict immigrant parents, Ahn would speed-read Baby-Sitters Club books at the library when her parents weren't around. It was in these stolen library sessions that she finally recognized a different way of seeing.

"Even as a kid, I just remember being like, Claudia's different because she's not a nerd," Ahn says. "She was artistic and cool and popular, and that was exciting because at the time there weren't really Asians in any kind of movie or media, and if there were, all of them were nerds."

That little bit of representation went a long way: today, Ahn is an accomplished actor who makes her living through the arts, an achievement she doesn't take lightly. "When you don't have role models, everybody--including you--is going to discourage you for obvious reasons," she says. "But when Asian parents actually see a road for their kids to [pursue the arts], it alleviates some of that fear."

~

As I grew older, I supplemented my ongoing literary education with a healthy diet of American pop culture; through the screen, I learned about first crushes, frenemies, and the sort of emotion-driven family dynamics that just didn't exist in my stoic four-person household. I saw white families on TV talk about their feelings at the dinner table, problem-solve together, tease each other, and exchange "I love you"s without a second thought.

I very rarely saw myself or my family on those screens. I remember how it felt to be "othered," to feel like I was always on the outside looking in. I had no true gauge of what was "normal" for my Taiwanese-American family because I had no point of pop culture reference, and the few Asian Americans that cropped up in the media were always used as devices, sidekicks, or a joke. Claudia still stuck out as the one exception, an example I could reference whenever I tried to make the point that Asian Americans weren't two-dimensional, could carry their own stories.

Then I stopped trying to prove the point; instead, as the late and great Toni Morrison encouraged, I started writing my own story. Our story.

~

For YA novelists Marie Myung-Ok Lee and Kat Cho, opting to write the stories they wish they'd had growing up, ones in which Asian Americans are the protagonists and the heroes, was sparked by a desire to regain agency following a lifetime of misrepresentation--or none at all. Lee, who penned what is widely recognized as the first Asian American YA novel, Finding My Voice, in 1992, says that she initially tried to write the story with white characters, but something felt off.

"As a narrative experiment, I said, 'Why don't I make the protagonist Asian American?' and 'Why don't I add details from my family?'" she tells me. "Later, I would hear from other Asian Americans who had similar experiences [of discrimination] and could relate to it. That was very satisfying."

"Growing up, I knew that I wanted to be a writer, but I had no idea that you could be a writer or that Asian American people could do things like that," she continues. "It was one of those secret things where I just told myself I would be a doctor but also a writer, and that I was going to somehow figure it out."

Lee would go on to help start the Asian American Writers Workshop in NYC, initially founded to assist Asian Americans who wanted to carve out space in their professional lives to write. As the organization grew, however, so did the strength of the community. And the more diverse perspectives were represented, the more layered and nuanced Asian American writers began to recognize their own experiences to be.

"Sometimes it's hard working for change because everyone has a different idea of what change looks like," Cho, the author of the YA fantasy romance Wicked Fox, says. "But what I've learned is that everyone's experience is valid and vital. And the issue isn't about what's the 'correct' experience to represent but how to present the most experiences we can."

Cho, whose debut novel incorporates Korean dramas into its storyline--something Lee calls "exciting"--credits characters like Claudia Kishi for making her present reality feel like a possibility way back when. "I loved Claudia because she was an Asian who wasn't just the stereotype of a good Asian girl who got good grades and was quiet and obedient," she says. "It was important to see that she was an artist."

~

As a child of immigrants, one of the things you eventually learn is that while your life and your story are never really your own, this is, in fact, a gift. Because when you write your own experiences, you are helping others to write and define their experiences, and the act of writing, of bearing witness to your own life in the context of your community, is a lifelong process.

Being part of a bigger whole means responsibility, yes, but it also means having a community and a chorus of voices to cheer you on. It means recognizing that you are not the only one who aspired to be Claudia Kishi, who clung to her character as a beacon of hope, and that your secret desire to be an artist, your creative superpower, was never just yours to keep.