Spurred on by Editor Kat’s ruminations about “ethical true crime” last year, I finally worked up the courage to talk about “my” favorite true crime story…from 1922. Well, it’s actually my grandmother’s story: when she was a little girl living on a dairy farm in Somerset, NJ, a stranger came by their farmhouse one day urgently in search of a telephone. Something awful had happened a few hundred yards away. Gram followed her older brother to a crabapple tree where a crowd was forming and saw for herself the lifeless bodies of the married Reverend Hall and his paramour Mrs. Mills, a singer in his parish choir. Gram always said, “I couldn’t understand why that lady was lying in the dirt in a pretty polka dotted dress, but when I saw the angle of her shoes I somehow knew she was dead.” Supposedly Gram’s bare footprints and her brother’s were in the first crime scene photos.

Fast forward a lot of years, and - still here in New Jersey — Audible’s Doug Stumpf mentioned the story to Bryan Burrough, one of my nonfiction-author heroes. Reader, I pitched him. And he took up the story of the famous, unsolved, hometown Hall-Mills Murder case. Sometimes even true crime has a happy ending!

Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly. PLUS: Bonus content at the end of the bottom of the text.

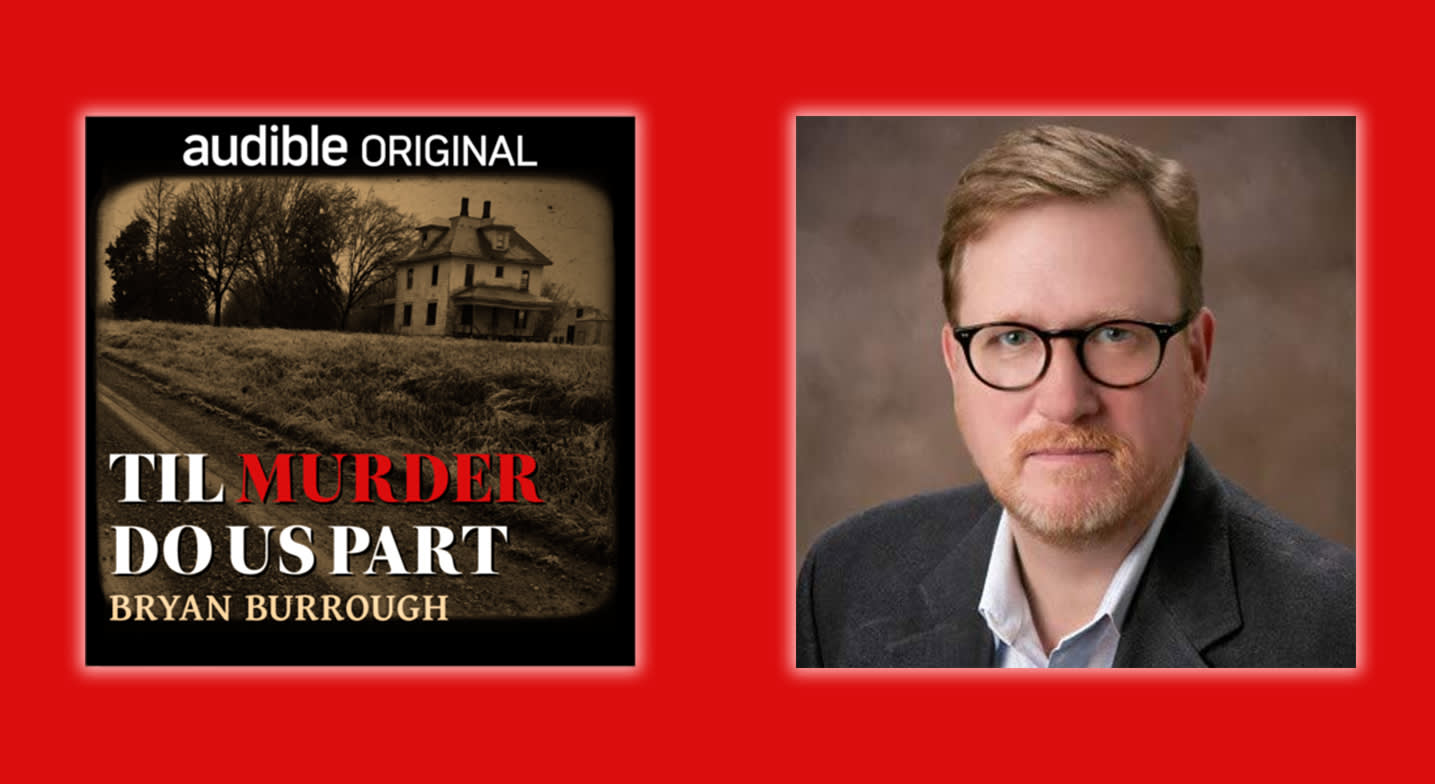

CH: Hello! I’m Christina Harcar, and I work at Audible. I have the pleasure today to be in the studio with the author and narrator and journalist, Bryan Burrough. Bryan, I’d like to welcome you to Audible and to settle in for a chat about your upcoming title, Til Murder Do Us Part: The Story of the Hall-Mills Murder Case.

BB: Well, thank you for having me. Every author, as you know, loves talking about his latest story. So, anything you’ve got, fire away.

CH: All right. Well, let’s start at the top then. Can you tell me a little bit about the Hall-Mills murder case, and what drew you to it as a subject?

BB: This is such a great story, because it is so rare to find actual cases that feel like an Agatha Christie novel. Actual cases that feel like a real life game of Clue. You know, actual cases where one suspect is advanced, but there’s equal evidence suggesting that that suspect is not involved. You know, it could have been Colonel Mustard, but his alibi is pretty good. And you’ve got that time and time again, in Hall-Mills. It’s like this beautiful little Rubik’s Cube from 100 years ago, that is still as perfect today as it was back then. It was a case that I had not heard of until you brought it to my attention. And I got lost in it quickly.

CH: Oh, that’s great to hear. Okay, so let’s talk about 100 years ago. 1922, almost 100 years ago, and the place, my hometown of New Brunswick, New Jersey, which I invite everyone to visit at some point in their lives. Could you please put the events of this case into context? I mean specifically, it was a media circus.

BB: Yeah.

CH: So, can you talk about that, and also maybe let me know which modern trial you would compare Hall-Mills to?

BB: Well, the first thing you have to realize is 1922 seems like an awful long time ago, because there are so few people who were alive then who are alive now. But frankly, the way America worked was pretty much the same. People drove cars. They went to school. They went to church. They read newspapers. Okay, they didn’t have the internet. They didn’t have missiles and men on the moon, but by and large, society as we knew it then, it’s pretty much the way society works now. And that goes especially for the media. You could say that there was a lot more media then. So, for every website today, there was a little newspaper. I mean, places like New Brunswick, you know, population 20- or 30,000, had two and three newspapers.

So there was an awful lot of local and regional coverage. And this also came at a time where you’re really seeing the rise of the first national newspapers, the New York Times, which wrote hundreds of thousands of lines about this. The Times really owned this case. You know, it had, what, another eight competitors in New York, plus papers in Chicago, all of whom sent in their own people to cover this. The New Yorker sent in people. There were radio stations in New York that were broadcasting portions of the trial live. They were expecting so much interest that they packaged up this thing for telephone operators specially made for the Gene Tunney heavyweight fight the year before — a machine where a 125 of them could sit around — and they put it in the basement of the courthouse in this little town of New Jersey, because of the expectation, soon realized, that the world was watching. And the world wanted to hear about this.

And the Hall-Mills case does not stand alone. It was not a unicorn for its day. You have to look at it as among a small series of trials that happened almost annually during the twenties. There was Sacco and Vanzetti. There was Leopold and Loeb. There was the Scopes Monkey Trial. There was the Fatty Arbuckle trial. It was almost like every year, somewhat like the nineties, it seemed like every year the press got together and anointed one new trial of the century. And, and in this particular year of 1926, Hall-Mills was that. It reminds me, in that regard especially, of the Menendez case from the nineties, because it’s so Labyrinthine. Because there’s so much to debate. There’s so much to talk about. And it was clearly a crime of passion, set within a wealthy family. So in that regard, it’s always, for some reason, held echoes of the Menendez case, for me.

CH: I definitely agree with you. Thank you for that. So which Hall-Mills participant, if you could pick, victims, suspects, law enforcement, witnesses… you have full panoply… which one would you pick to question directly? And you can assume they would tell the truth. And what would you ask?

BB: Oh, no question. I would want Willie Stevens. Willie is the oddball brother who lived with the wealthy couple in the mansion. And he was a strange bird. Some thought that he was mentally challenged. Clearly he had some behavioral issues. But he, you know at times, he summered by himself. He lived by himself from time to time. But he didn’t work for a living. He spent most of his days at a local firehouse, polishing things, and helping the firemen. And when he wasn’t doing that, he was walking around the Hungarian neighborhoods of New Brunswick, running errands for the local merchants. And this was a man who was easily worth in the millions. I think that if you talked to 10 people knowledgeable today about Hall-Mills, I think seven or eight would list Willie among the smallest group of prime suspects.

So if I could do one thing, it would be to meet Willie as he came down to breakfast in the mansion, have breakfast with him, go with him to the firehouse, walk around the neighborhoods, and just spend the day talking with him in an unguarded way. I think we’d have the truth.

CH: So these [next questions] are guilty pleasure questions. They’re just all about true crime. We have so many listeners who love true crime. And at least half of the Audible editorial staff loves true crime. We spend a lot of time thinking and talking about it. So please tell me, what in your background, or in your perspective, [inaudible] what drew you to true crime, in general?

BB: All right. You know, we could do this for a long time, because true crime has been kind of a backbone of my identity as a writer. If anybody out there knows me, they may know me largely because I’ve written about business, and Wall Street, for the better part of 30 years. Some of my most recent books have been about 20th century history. One of the frustrations I always had about writing in the conventional magazine world, at Vanity Fair, and other places, is they always want me to write about big money, and big business, that type of thing, when my first love, and greatest love, has always been true crime.

I cannot tell you how many times I’ve gone to magazine editors and wanted to write about this fabulous little murder in Iowa, or four girls found dead in Austin, Texas or something, and it just wasn’t right. Or you know, they never wanted it. When I came to Audible, I said, “Wow, you know, my first love is true crime. That’s what I want to write.” And Audible was like, “You go. We love that.” I can’t tell you what the first book I read was. But the first adult book I read, that stayed with me, was In Cold Blood. Truman Capote, 1965, obviously.

And that changed the genre. In some ways, it introduced the genre. I probably didn’t get around to reading it until I was 14 or 15. So ten years later, in the mid-seventies. But at that point, I pretty much ate up every piece of true crime that I could find. For those listeners who read a lot of it today, but may not be aware of older books that are so fantastic, I would recommend the second and third most important books to me, by the Texas-born writer Tommy Thompson, from both… I would say from early to mid-1970s.

The first was called Blood and Money. A famous story of a strange couple of murders, or deaths in the wealthiest part of Houston. That was fairly well-known. Less well-known is his follow-up book, which had an even greater influence on me. It was called Serpentine. It was about an Asian serial killer, Charles Sobhraj, if I’m not mispronouncing his name. Born in Vietnam, was accused of a wild string of jewelry thefts and murders throughout southeast Asia, and India. And you know, it’s conventional true crime. But what Thompson did was… bring in the sights, smells, and sounds of a foreign, exotic to me, world that showed me, at an early age—and I’ve gone back to this book several times while writing other books— the importance of taking a reader to the moment, to the extent that you’re able to accurately report sights, sounds, and smells. To really bring a reader to the place.

So I’ve always loved that book. I’ve recommended it to so many people. When I finally got around to writing, books myself, my first book, co-authored with my great friend John Helyar in 1990, was called Barbarians at the Gate. It was the story of the largest ever takeover fight in Wall Street history. Which would seem to have very little in common with In Cold Blood, and Blood Money, and Serpentine. But I went and wrote Barbarians at the Gate, very clearly with all the conventions of true crime.

You know, Henry Kravis, the billionaire who won, I wrote about him as if he’s walking across that boardroom, not with a contract in his hand, but a bloody ax. I used all the conventions that I learned in true crime, and took them to business journalism. Barbarians, let’s just say, did have some influence on the way business books are done. It popularized the idea of business narratives, if nothing else. And a large part of that, were the conventions of true crime. And you know, I continue to read it to this day. It is my first great love. And thanks to Audible, I now get to plunge back into it.

CH: Oh, that’s great. And I feel like somewhere in there you may have given us a hint of what your next work is.

BB: [Laughs]

CH: I won’t pry, but I can’t wait. And my final question is, since you’re so well-versed in true crime, would you feel like sharing, which crime, current or historical, any one of them, do you think you might, in another universe, be guilty of participating in? And alternatively, which one never?

BB: Well, I’ve thought about this.

CH: [Laughs]I know you have.

BB: We all, in our lives, whether committing a crime, or just doing something we’re not supposed to… I have the worst sense of guilt. I forever worry that I’m going to get caught doing something, and somebody’s going to come get me and take me away. So I would never do a crime, and if I were really never going to do a crime, I could never do anything like murder. I could never dispose of a body. You know, it’s one thing to kill somebody with a gun, and turn your head. But you know, if you’re going to get away with it, you have to dispose of the body.

And having written about this many times, about how to do it, and suitcases and tubs, and all that, I just know I could never do it. That would never be me. If I was going to do a crime… if I was going to be ever guilty of anything, it would be white-collar crime. I would be an insider trader on Wall Street. I would leak to Michael Milken, or Ivan Boesky, or some of those guys from the ’80s, make 10, 15 million dollars, buy a Park Avenue apartment, maybe a place in the Hamptons. I would be that crook.

CH: Okay. Well, that’s good to know. And you know, the fact that you’re still an honest writer lets me know you haven’t gone down that path. [Laughs]

BB: [Laughs]No, I don’t want people coming after me.

CH: No, I know. But I really appreciate your candor on that question. I really enjoyed hearing your answer. It’s not just authors and audio producers, book lovers sit around all the time and think about where am I in this true crime? So that was a really wonderful response. And I thank you for your time today, and for all of these responses.

BB: It’s my pleasure. I wish all interviewers had such fun questions.

SPOILER: Bryan Burrough

shares what he really thinks happened with the Hall-Mills case.