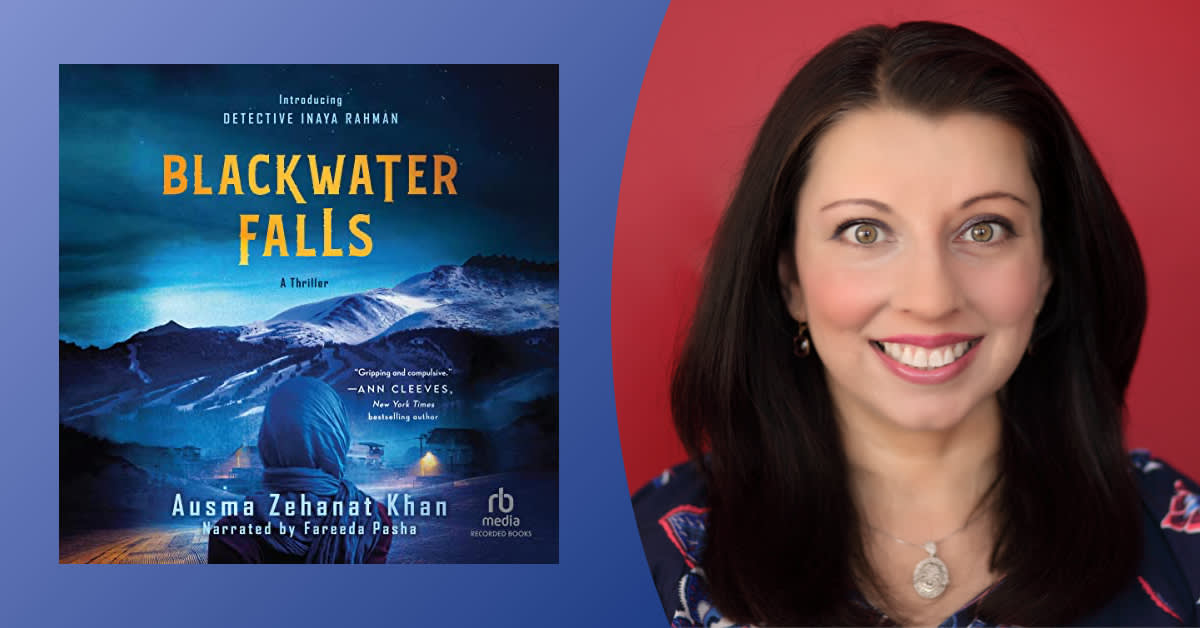

Since 2008, critically acclaimed author Ausma Zehanat Khan has made Colorado her home. As a South Asian and Muslim woman who had previously lived in large multicultural cities, Khan is well aware of the irony of a place with spectacular vistas but a social landscape that doesn’t bode well for many, specifically minority communities.

Detective Rahan, the star of a new mystery series that launches with Blackwater Falls, gives Khan an ideal vehicle to poignantly and effectively channel her own experiences without entering the world of make-believe. She supplies the character all the fuel and the determination she needs to look after the underserved, especially missing girls of color whose lives continue to be undervalued. All the while, we gain insight and peek into a place we think we know, with its splendid natural beauty and the other side that lags behind.

We asked the creator of Blackwater Falls to tell us more about why her new title and character are so significant.

What inspired you to write a crime series following a female American Muslim detective who investigates the cases of missing girls of color?

Crime fiction is possibly my favorite genre to read and write, but you don’t often see characters like Detective Inaya Rahman. I wanted to write a character who was intimately familiar to me from a background like my own—South Asian and Muslim. And I thought a detective of color would be able to empathize with and investigate the disappearance of girls of color, in ways we don’t often see in crime fiction.

You don’t see many American Muslims’ stories set in the middle of the country. What made you pick Colorado as the backdrop of the series, and why is it so important to tell American Muslim stories set here?

I’ve been living in Colorado since 2008 and it’s such an interesting state to me—highly conservative in rural and poorer areas, strongly liberal in the university towns. It makes for some interesting politics and a fascinating backdrop to set a crime novel against. Most of my life, I’ve lived mainly in large, multicultural cities. Now I live in a small, rather homogeneous suburb—it’s such a contrast to everything I’ve known. It’s an absolutely fascinating microcosm of American culture and society. I was interested in the question of whether minority communities are able to thrive in places where it’s easy to be singled out and harder to find common ground.

Is Blackwater Falls based on any particular part of Colorado? How did you integrate the unique history of the state and its relatively small but powerful Muslim community into the story?

The areas I had in mind are the suburbs and small mountain towns south of Denver—Castle Pines, Evergreen, Littleton, the Chatfield reservoir. I’ve explored a lot of Colorado since I’ve been here—the Rocky Mountains, the backcountry, the parks, the reservoirs. Of course there are issues such as wildfires, droughts, and race. Once, I accidentally drove up to the highly secure, no-entry gates of Lockheed Martin; another time I got lost and ended up at a military base up near Leadville—these are places where brown people are automatically deemed suspicious. I wanted to put all of those experiences into my story—the sense of Colorado’s relative newness along with the great disparity between wealthy and poor communities populated with migrant workers. And of course, I wanted Colorado’s magnificent scenery for the backdrop of the story.

How would you define Detective Rahman’s definition of justice and empowerment? Does it reflect your own experiences as an American Muslim woman living in Colorado?

Detective Inaya Rahman tries to do the right thing in very difficult circumstances: working for law enforcement, as a woman of color and a Muslim. Because she’s experienced discrimination she knows the imbalance of power between law enforcement and minority communities. She understands what it’s like not to hold power in your hands and to be at the mercy of people who refuse to understand you or who treat you as less than human. To deliver justice to these communities, she has to overcompensate to make up for the shortcomings of others. Yet the question is whether she can serve minority communities adequately while working for a system that is designed to work against them. She has internal contradictions to resolve—where she belongs and what she stands for. She’s guided by her faith, has to accept the simple fact that no system is perfect, and sees the necessity of keeping an open mind.

Unlike Inaya, I don’t wear a headscarf and no one can tell I’m Muslim, unless I identify myself that way. But I’m plugged into a large community of family and friends across the country and in Canada. I also study hate crimes against Muslims, so Inaya’s experiences are reflective of the poisonous current of anti-Muslim racism that many Americans aren’t even aware exists. It’s like living in two separate realities and trying to make them make sense.

What are some other stories by and about Muslim women that inspire you?

I love Uzma Jalaluddin’s romcoms, like Ayesha at Last and Hana Khan Carries On. They speak very clearly and poignantly about how our communities deal with Islamophobia, while remaining lively, heartwarming and wonderfully empowering. Sahar Mustafah’s The Beauty of Your Face was an exquisite novel about a Palestinian-American woman who finds her way back to faith, only to face a school shooting at her Islamic school. Nafiza Azad’s fantasy novels feature female protagonists whose faith empowers and guides them: The Candle and The Flame and The Wild Ones are sensitive and beautifully told stories. Laury Silvers’ historical Sufi mystery series (The Jealous, The Lover, The Unseen) is some of the best historical fiction I’ve read, her books have a deep spiritual resonance. But the Muslim woman whose work has most inspired me is probably the great Moroccan feminist, Fatima Mernissi. Her books The Veil and the Male Elite, The Forgotten Queens of Islam, and her memoir Dreams of Trespass have all been hugely influential in my life.