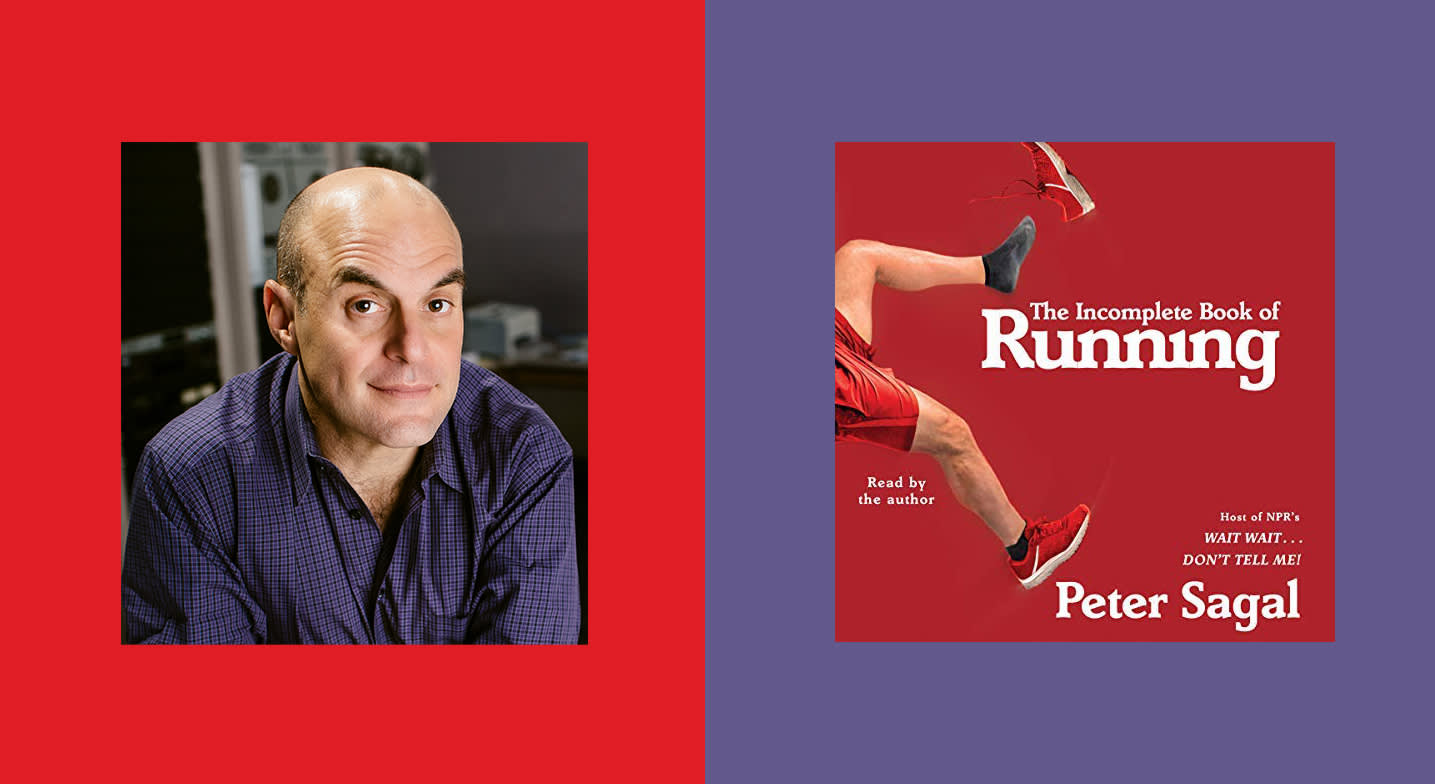

Peter Sagal's voice is one that listeners of NPR's long-running Wait, Wait..Don't Tell Me! are intimately familiar with after his 20 years as the humorous host with the quick wit and hint of a smile you can often hear. Now a new crop of listeners will get to know that voice as he narrates The Incomplete Book of Running , his new book about running that goes well beyond the mechanics of the sport and into the heart of what he does: storytelling.

Sagal, who's also been a popular columnist for Runner's World for 10 years, weaves humor through the many poignant moments he's experienced and life-shaping lessons he's learned as he's picked up long-distance running in earnest, running 14 marathons and logging tens of thousands of miles on roads. Sagal called into Audible HQ to talk about the why of his book with editors Courtney Reimer and Abby West, fans of both of his domains.

Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

Courtney Reimer: First, welcome to Audible via audio. It's me, Courtney Reimer, here with fellow editor Abby West. I'm a longtime listener, and Abby is Audible's resident runner.

Abby West: I am one of the people around here who runs, and I am far less a runner than you are, Peter. But I love running.

CR: I wondered how writing a book and then voicing the audiobook felt for you, as a veteran of audio. Did you feel comfortable narrating your book? How did it compare to being a host of a radio show?

Peter Sagal: Well, it was actually quite different. My engineer, when I did the audiobook, was impressed. He said, "Oh wow, you're clearly a pro. You know how to speak into a microphone." And I would get all smug about it. But fact of the matter is, it was really quite different in, god, I don't know how many ways. First of all, on Wait Wait ... Don't Tell Me! if I talk for more than a minute, if that, something has gone very wrong. Because Wait Wait ... Don't Tell Me! is not the Peter Sagal Show, nor was it ever designed to be. It's a conversation. And if I'm talking that much and nobody else funnier and smarter, like say Paula Poundstone, or Adam Burke, or Alonzo Bodden, is chiming in, then something has gone desperately wrong. So it was a little strange just to speak without interruption. I felt a little at sea. I usually use my collaborators as a crutch because I get credit for them being charming and funny. So that was a little weird just to speak without interruption or handing it off to anybody else. The second thing is if anybody out there is feeling a little too proud, a little bit too smug, about their prose style, I recommend reading it aloud into a microphone with an engineer silently staring at you and you will regain your humility pretty quick. In fact, I actually found myself regretting that I hadn't read it aloud just to myself before I finally submitted the copy because, man, that really shows your flaws in your supposedly sterling style.

CR: Did you find yourself modifying at all when you went to the audio form?

PS: I did. Somewhat surprisingly, because I've been working with Simon & Schuster and these guys are pros. And it's been polished, corrected, queried, re-queried. I mean, I actually had a lengthy, if hilarious, argument with one of my editors about the quote, "You see, I had no place else to go," in the book. I wanted to quote Nabokov's Lolita. The editor wanted me instead to shift the quote to, "I got nowhere else to go," as shouted a in An Officer and a Gentleman by Richard Gere. I mean, this actually became an argument back and forth like Lolita, Richard Gere, Lolita. And I went for Lolita because I didn't want to privilege Taylor Hackford over Nabokov. But that's the kind of level we were arguing about. So when I sat down to read my book into a microphone for the audiobook, I thought it had been set. It had been done, everything was perfect and boy, was I wrong. So, yeah, I ended up transposing a few words and trying to cut down on the number of repetitions of my favorite phrases, that sort of thing.

CR: And you know, getting into more the meat of the book itself, had you read or listened to any running books before going to this yourself?

PS: With a couple of notable exceptions, I have not read many running books. And this is a very strange thing for a guy who just wrote a running book and recorded an audiobook of a running book to say: I'm not sure if reading books are all that valuable.

AW & CR: (Laughter.)

PS: I'm guessing you guys, and maybe a lot of people listening to this, are too young to remember this, but The Complete Book of Running by Jim Fixx was, as I put it in the book, the Koran of the huge '70s running boom. Everybody had a copy of that book, and that book must have inspired more people to run than anything else in American popular culture. It was a huge book. My father had a copy, and I read it back in the '70s, and it was one of the things that got me running as a very young man and I recently re-read it. And what's interesting about that book is that it doesn't have a tremendous amount of substance in it other than constantly repeating, "Running is really good for you. It really is. Boy, if you run, you'll lose weight, you'll feel better, you'll have a better sex life, you'll feel more awake, you'll be able to eat more, you'll be generally healthy or you'll ..." I mean all these things and they're all true. But do you need a book to say it?

AW & CR: (Editor's note: we sure hope so!)

PS: And I know I'm talking myself out of sales here, the other book that I read and thought about a lot was the book by Murakami called What I Talk About When I Talk About Running. Murakami is, of course, the great Japanese novelist who's famous world over, and he's an enthusiastic runner. And what I found out when I read that book is that what Murakami thinks when he thinks about running is just as boring as what everybody else thinks about when they think about running.

AW: Yep. (Laughs.)

PS: It turns out that what he talks about when he talks about running is just as boring as everybody else. So all of that said, when I sat down to write my own book about running, I wanted to do two things. First of all, I didn't want to oversell the technical aspects of it. I mean, my advice to people who want to run is, "Go run." And I have a little bit more to say about that. I think there are ways to start, there are ways to continue, there are things that'll help you, there are things that won't help you and I go over that. But mainly what I also wanted to write about is the experiences I've had when I've run. And those experiences have ranged from just being alone in a beautiful spot of undiscovered country in Yellowstone National Park and also being quite near the Boston Marathon bombings in 2013. I always think that the value of any experience is directly related to the quality of the anecdotes that come out of it. So I'm hoping that the anecdotes that I can provide after some decades of running are worth people's time.

AW: I kind of love that. I have listened to What I Talk About When I Talk About Running and yes, it is boring. But I love the, what is it, the universality of running with we're all sort of in the same space. You're-

PS: Yeah, we're all pretty dull.

AW: Yes, pretty much. And I love that Murakami is just a dull as I am when I go for my run across the street in the park.

PS: It does have that value that he is just as mundane. "What's that in the bottom of my shoe," said the presiding genius of Asian fiction. That's great I guess, leveling.

AW: So given all of that, I know you wanted to pepper in the anecdotes and what not but why do you think there is a value for your book in this current environment? I kind of get the complete book before. People needed to have it drummed into their brains that running was good. And now, you're taking it to another level.

PS: This is what I think. And if I have one message, one hope for a message that gets across, the thing that I'm evangelizing for is something that I summarize as, "Get outside." And what I mean by that is a bunch of things. First, on the literal level, "Get outside." We were not born to sit in cubicles under fluorescent light. Go outside. There's interesting things out there. But more metaphorically, one of the things that we all deal with these days is the fact that we basically use our bodies to transport ourselves from screen to screen. If people are reading this, they're probably reading it on a screen. If they're listening to it, they're listening to it from a device. We have constant input, constantly. In fact, one of the things that makes me a little sad is going to gyms and seeing people on treadmills and they're just staring at another screen.

I mean, I know people do this. I've done it. I did it yesterday morning because I've got an injury and had to go use an elliptical machine instead of going from my run. But I think it's not good for us. And I think running, which is available to everyone almost anywhere, is an amazingly simple way to just go outside, get away from the screens, get away from input. Remind yourself that your body is for more than, like I said, carrying your head around. Remind yourself that you were not, in fact, born to sit in chairs and stare at things and manipulate symbols, as somebody put it. You're actually born to run, to coin a phrase. And I hope that some people pick up the book and are inspired to stand up, go outside, and go for at least a brisk walk.

CR: You may not have coined that phrase, actually.

PS: I know, I know.

CR: I'm kidding, I'm kidding.

PS: Getting cocky. I'm hoping it catches on.

CR: Well, we are in New Jersey after all. So ...

PS: Oh yes, that's true. So who knows.

AW: There's that. To that input point, I'm fascinated by the fact that you don't always run or you never run with headphones on? I couldn't tell if it's just sometimes.

PS: I prefer not to. And like everybody else, you know, I don't drink except for, you know, beer. [Laughter.] I do, like a lot of other people, when I'm on my own, when it's kind of miserable out, when I don't feel like spending all that time I my head. Yes, I will listen to a podcast. In fact, I've gotten into the habit of going for a run in the mornings these days, taking my dogs and listening to The Daily on the New York Times podcast, no offense to you promoters of wonderful podcasts. I will say that I had a wonderful, a lengthy run listening to The Butterfly Effect just last summer.

CR: Aw!

AW: Well done.

PS: And it's a little bit like running itself in that there are days, and anybody who runs knows this, that if you get up and you're like, "Oh man, I'm so tired and maybe I can just sleep." And then as soon as you get yourself out the door and you get through that first half mile or mile, all of a sudden you realize, "Oh, this is great. I'm enjoying it. I'm so glad I did it." Similarly, sometimes you look upon an experience where you won't have any input. "Oh god, it's going to be so boring. Oh god, what am I going to do for out there for 45 minutes?" And then once you get out there without your headphones and your mind starts to free itself and you start to think and you start to cogitate and ideas come to you or things you haven't thought about or people you haven't remembered. All of a sudden you're like, "Yeah. This is actually a good thing." It's as close as I ever get to meditation and is as necessary for me as meditation is for those who practice that.

CR: This leads into a question I was going to ask, which is clearing the mind and thinking about more important things than whatever might be going in your ears, with all due respect to what we do here. Did you write your book at all in your-

PS: Yeah, one provider of content to another and saying, "No. People should stop listening to podcasts". Yes, exactly.

CR: (Laughs.) Did you write your book in your head at all while you were running?

PS: A lot of times, yeah. As a matter of fact, I mean certainly many of the experiences that I write about occur during runs. And I started to think about what I was experiencing while it was happening. So in many ways, what I'm writing about is a thing that came to me while I was running, thinking about running, during running. So in a weird way, this is my version of What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, although I hope what I talk about is more interesting. Apologies to Mr. Murakami.

AW: I will also ask you about the fact that you pushed for us to run in groups. I'm really against that.

PS: I know. Everybody is.

AW: So you call us out of the whole solitary running thing. But, yeah.

PS: This is the thing that most people are resistant to when I suggest it. And that's because of a bunch of reasons. First of all, it's hard to socialize. You have to sort of make plans with people. You have to find people. Secondly, there is this image of running alone like the picture on the cover of my book. The picture on the cover of Jim Fixx's book. The picture on the cover of Murakami's book. We're all alone. It's all this striding across the landscape free, solo. But the fact of the matter is that I only went from being an amateur midlife crisis runner of middling achievement if none to an actually pretty good runner with a bunch of marathons under my belt and some pretty good times because I found a group of people to do it with. And without them, without their company, without their encouragement, without this constant incentive to get up and go out because everybody's getting together at 6:00 AM or whenever it is and you have to be there to meet them, I never would have achieved what I achieved. And I think that again, it's like one of those other things we were talking about that doesn't seem like a good thing or worth the time before you do it. But once you do it, once you make that leap, you'll find out it's hard to get by without it.

CR: You sort of alluded to what precipitated you becoming a serious runner again. Talk to me a little bit about -- I don't know. I don't want to speak for everyone, but I think when people think of Peter Sagal, they think humor.

PS: Yes.

CR: And this has humor in it, but it also has some darker themes of mortality, tragedy. Talk to me about shifting from humor to more serious topics and how that works for you.

PS: It's easier for me than you might expect. Everybody expects that somebody in my line of work is and was the class clown. The guy or the woman who always reflexively goes to humor in any situation. And I was the class clown to a certain extent, but I think more than you might expect, a lot of us people in this business have, not only do we have a serious side, but we sometimes yearn to express it. Just the same way that, to take on immediate example, Bill Kurtis, my cohost on Wait Wait ... Don't Tell Me! thrives and loves being funny after a lifetime of being the most serious anchorman. Carl Kasell is the same way. I actually enjoy the opportunity to not be funny for a little bit because I have some other things I want to say. And that, when I was a playwright, which was my career before I got into radio, I wrote pretty serious plays leavened with jokes.

I like jokes. I think people deserve to laugh. It's fun. But there are other things that I wanted to talk about, including the fact that humor is one of the ways you get through tragedy. A lot of people have come up to me over the many years we've been doing Wait Wait ... Don't Tell Me! 20 years, as you say, this year. And for many, many years they've been coming up and saying, "Oh, your show got me through," oh, I don't know any illness, the loss of a parent, the loss of a son or daughter. It's a loss of a job. Some other crisis. And they found my funny radio show to be helpful. And I should say, I'm extremely grateful to that. I think it's an honor to play that role in people's lives. But what these people don't know, sometimes I mention it, is that the show did the same for me. I've been through some difficult times, myself, some of which are alluded to in the book. And if it wasn't for the chance to go on and do this radio show every week, to be funny because it was my professional obligation, to put on a good show, to be in a good mood professionally, I don't know if I would have gotten through them as well as I did or at all. I don't know if that answers your question.

CR: Yeah, no, no, sorry. Abby and I were looking at each other because one thing that runs through sort of peppered throughout is the Boston marathon. I mean, talk about dark things that happen. Did that change your perspective on marathons or running?

PS: Well, it's interesting. There are actually two events in the book, both of which are in the book. The marathon bombing was really, I don't know what the right word is. I've always been very, very careful about talking about it because I hope I have never referred to myself as a survivor of the Boston Marathon bombing, let alone a victim. God forbid that I should ever let those words pass my lips when there were people who were seriously injured, traumatized, and killed. And I was none of those things. But I was a witness. I was there. I saw it. I came really close to being exposed to it in a very dangerous way. I tell the story in the book how we just, obviously unknowingly, slipped by the bombs right before they went off and how close we came to being right in front of them.

And that incident in 2013 and another incident in 2010 where I was hit by a car while riding my bike and I guess nearly killed. Those certainly have a way of changing your perspective. It certainly helps you understand how what you might think is due to your virtue and your hard work and your qualities as a sterling human being have a lot more to do with luck than anything else. And that you should be a lot more grateful for the good things that come your way than you might otherwise be. And I think it also, and I don't know how much I read about this, but it certainly has changed my view on how to conduct myself in the world because terrible things can happen at any moment to anybody. And it's incumbent upon us not to try to add to the tragedy or pain in anybody else's life given how much of it comes unwanted.

CR: Well, you allude to two very serious tragedies. Talk to me a little bit about how running may have helped you through another, I don't know tragedy is the right word, but the dissolution of your marriage.

AW: I'll just jump in and set that up as well because that really resonated for me because I started running again about 10 years ago when my marriage ended and I needed... I don't know what I needed. But I found it in running. And when you wrote it, there were some lines you had in there that really resonated. So how did you feel exposing that in the book?

PS: Well, I mean, I need to be very sort of vague about this, but my situation was slightly, well not slightly, it was more than a mere dissolution of a marriage. Sometimes that can be a good thing. Sometimes that can be a bad thing. Sometimes it can be a thing that's ultimately positive for both people involved. My situation was slightly different and because it involved a vast and negative change in my relationship to my daughters, which has been something I've been struggling with for a while now. And so when I think and talk about that, I'm mostly thinking and talking about that particular aspect of it and certainly running helped me in two ways. It helped me as sort of a constant in an otherwise extraordinarily tumultuous period of change. I mean, I went from being a husband, father living here to divorced guy, estranged kids living someplace else.

Everything in my life changed and running was sort of this constant. It was something I could keep doing. Something I literally escaped to. In fact, that's what I was doing at the Boston Marathon in 2013. I was getting the hell out of an impossible and possibly painful situation in my home. But even more important, there are two sort of standard bits of wisdom when it comes to running, particularly when you're having a tough time. The first is run the mile you're in. If you're running the first two miles of a marathon, don't worry about the fact that you have 24 of them to go after that. Just run those two miles in the way you need and want to run them. Keep present, stay focused. You're there.

And the second thing is that all runs end. If you're miserable and I've been miserable running in cold weather or in pain or cramping up or whatever it might be, it will come to an end. It's not permanent. And one of the things I acquired through a decade of serious running was what I call the practice of persistence. That is, you just keep going and that more than anything else I think helped me get through what I had to go through. The idea that it was really tough right now. This is terrible, but it will end. It will change. Something else will come. This moment will pass and things will get better. And while that may or may not have happened, it certainly helped to keep me sane during the toughest times.

CR: Well, I mean, I think that's a pretty good note to end on and we really appreciate your time.

PS: Sure. Yes, I hope so. I hope we provide some comfort in these generally difficult times. The nation is in the middle of a pretty tough marathon, so let's just stay in the mile we're in and try to keep cheerful about it.

CR: I love it. Thank you so much Peter Sagal. We really loved hearing from you.

PS: My pleasure talking to you all and the thanks for the fine audio content.

AW: Likewise. Thanks so much.