Note: Text has been edited for clarity and will not match audio exactly.

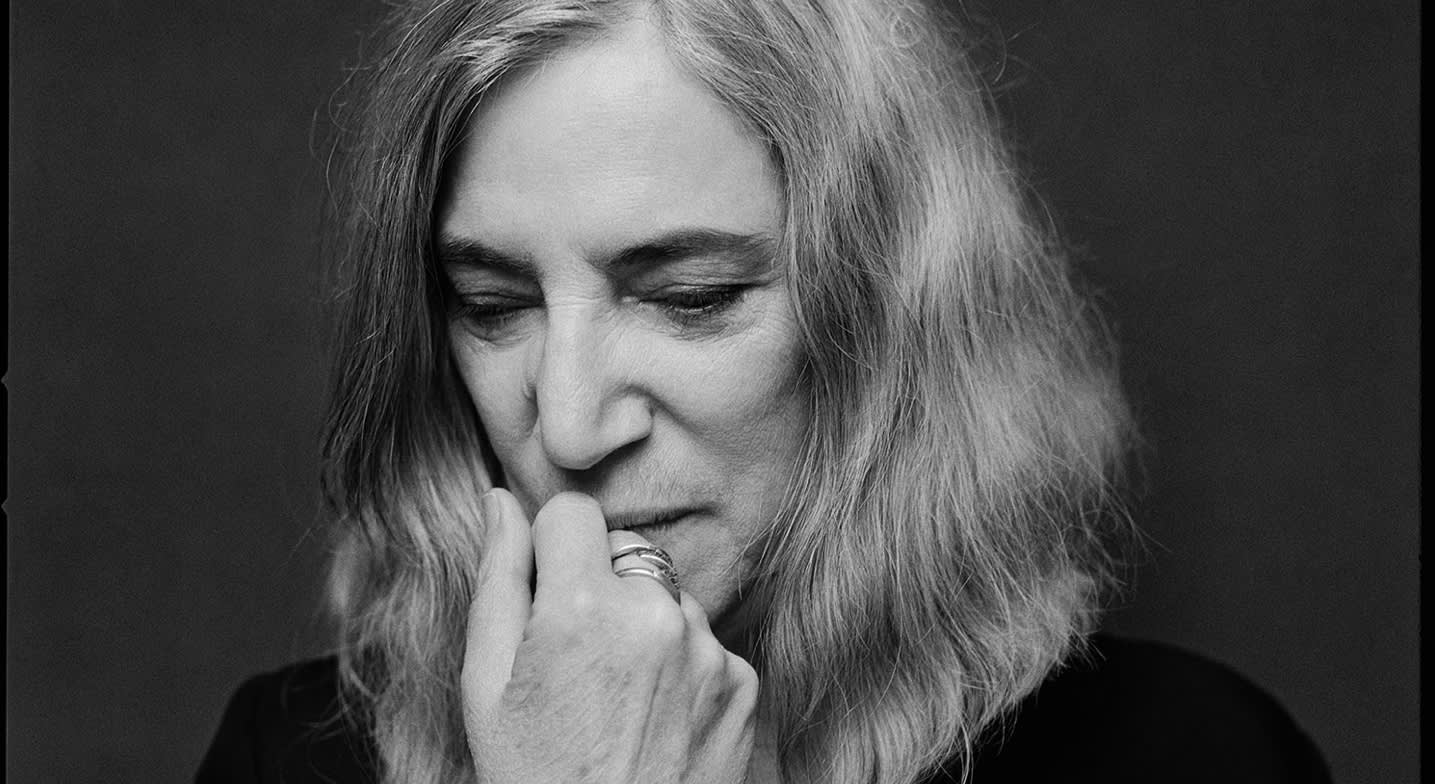

Patti Smith is a legendary writer, performer, and visual artist. A member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame since 2007, Ms. Smith gained recognition in the 1970s for her revolutionary merging of poetry and rock, showcased most notably on Horses, hailed by Rolling Stone Magazine as one of the Top 100 Albums of All Time. As an author, Patti Smith is equally accomplished; Her 2010 memoir Just Kids, a chronicle of her relationship with photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, won the National Book Award for Nonfiction. Today we’re speaking with Ms. Smith about her latest book, a memoir entitled M Train.

Audible: Patti, before we get started, I just wanted to say congratulations on M Train.

Patti Smith: Oh, thank you.

A: I think most people feel the same, but your work always makes me feel so woefully ignorant about literature that I don’t know quite what to do.

P: It’s not meant to do that. It’s really meant to share. I’ve read other people’s books and didn’t know half the references. I know there’s a lot about books, but it’s really just a way to share with readers some great books.

A: How did it feel to begin a new book with the knowledge that your previous one, Just Kids, had won the National Book Award? Did it change the way you approached M Train or your new work?

I love that Jimi Hendrix quote where he goes, “Hooray, I wake from yesterday.” That would be my mantra.

P: No, absolutely not. In fact, quite the opposite. I’m so honored to receive the National Book Award. I know what people loved about the book and I actually even anticipated what kind of book they would like next, which eventually I’ll give them, but I wasn’t ready to write it. I wasn’t ready to write a companion to Just Kids which would have a lot to do with music and other aspects that people seemed interested in. I needed to write something different. I didn’t let the award color my trajectory. I just simply have enjoyed it.

A: You just said you weren’t ready to write the complement to Just Kids, so what would you describe M Train as?

P: I think in terms of the book that came out, I would say happily irresponsible … because when I wrote Just Kids, I had so much responsibility. Robert Mapplethorpe asked me to write it the day before he died. I had never written a work of nonfiction. I know exactly what he wanted me to write, but I had to go through nonfiction writing 101 on my own. I realized as I was writing it that I had responsibility to every single person that appears in the book, to the time frame of the book, to my relationship with Robert. To Robert as a human being.

It took me some years to do. It was a sort of blessed burden to write the book. My main objective was to give people Robert. In writing this book, I had no agenda. I had promised no one anything. I guess in a way, it’s just a little book to give the reader perhaps a little of myself and my process. If the reader was curious to see how I live, how I write, what my process is, and also how one … negotiates getting older, aging chronologically. Not necessarily mentally or not necessarily losing any creativity or any spark or enthusiasm, but actually chronologically aging.

Robert Mapplethorpe asked me to write it the day before he died.

A: That’s really interesting, because unlike Just Kids which has a chronological thread that just sort of runs through it, this book seemed much more nonlinear to me.

P: The funny thing is that I found this book more linear than Just Kids because this book was written in real time. It’s my train of my thought in real time and it all takes place within about two years and it does mark time all the way through it.

The book does not look back. It’s written in real time, but it’s me as a writer, sitting in a café in real time reminiscing about the past. This is a book that’s moving along daily in my daily life and then slipping back and thinking about Michigan or my childhood, but thinking as I’m walking down the street or sitting in the café in real time.

A: The first line of the book reads, “It’s not so easy to write about nothing.” That’s an amazing first line. Why would you start a book that way?

P: Well, because in all honesty, I dreamt that. That’s a real dream. I woke up in sort of an agitated mood and I went to my café with my notebook and I was thinking about that and I thought, “Hmm, it’s not so easy to write about nothing.” I write all the time, so I thought, “Well, I could write about nothing all day long.” I can just sit and write about nothing, so I decided then and there that I was going to start with the dream and just write every day about whatever came into my head.

It was an experiment, really. Life unfolds and not without design. In the chaos of life, in writing this, it was very interesting because patterns were emerging. I didn’t think I was going to write about my husband. I never dreamed that I would be writing so much about Fred. He was very private and I had never written about him.

I was very surprised that he kept surfacing, but also [at] certain themes that surface. The theme of loss, the theme of detectives, but that wasn’t all thought out. Nothing in the book was thought out. It’s totally organic. It’s like one long improvisation that, in the end, there is a rhythm and sense to it because there’s a rhythm and sense to life.

A: You’ve said M Train stands for this mental train.

P: Yes.

A: Could you expand on that a little bit, because M seems to keep popping up in the book also?

P: I actually found that amazing. I just decided to call it M Train as in a mind train. That’s what it was for me. A mental train, the train of thought. Not simply just stream of consciousness, but something close to that. As the book, again, unfolded, there’s all these things, Michigan, Murakami, Mankell, mystery, mother, all of these things. They just found their way into the book and it wasn’t until I finished the book that I really noted how many M-themed words there were.

A: On the subject of trains and travel, travel definitely plays a central role in M Train and also in your life, seemingly. Why are you always on the move? Because it’s surprising that you travel so much when everyday routine seems to be so precious to you.

We all have a finite time.

P: Partially, it’s because it’s how I make a living. Now I’m going to be spending more time writing, but I do have a band and a lot of my travels have been because I’m touring. Also, I have friends scattered throughout the world. Sometimes, it’s just to visit friends or to see what my friends are doing. I tried to play that down because … Sometimes, people think you’re bragging. I wasn’t trying to write about my accomplishments.

A: It certainly did not come off that way.

P: A lot of times, I’m traveling because I go to do something charitable and then I just stay for awhile sort of roaming around. If you keep writing about that, it makes you seem like you’re trying to draw attention to yourself and that’s not what the book is about. I wanted the book to be more human. I mean eccentrically human because I’m not saying that I’m the average person, but I had to build to this. I spent 16 years as a mother and wife where I rarely left Michigan and my whole life was centered around my husband and children with a certain segment of my time put aside for writing.

When I was young, I helped raised my siblings. I worked in a factory at 16 to help my parents afford the cost of food. I worked for six years in a bookstore in the 60s and early 70s. I have a sense of responsibility, but at this point, I’m a widow, my children are grown. I’ve prospered and I can sort of go where I wish as long as I’m healthy.

A: Can you tell us about the Nawader and what it meant to you and your late husband, Fred?

P: Both of us left public life in 1979 and we got an old house on the canal outside of Detroit and we lived quite simply and happily. Fred really loved boats. I had no interest in boats, really. I don’t even swim, but we found this old boat up in Saginaw somewhere and we got it so cheap that a lot of people warned us that it probably wasn’t seaworthy. It was a 30-foot Chris-Craft. An old wooden ’50s Chris-Craft and it was beautiful.

Our life was very magical.

We hauled it back to Michigan, put it in our yard. Well, it turned out it wasn’t seaworthy but we loved it so much … In the summertime or in early fall and spring, we spent a lot of time sitting in it, listening to Tigers games or just talking. It’s like you want to leave the house and go somewhere. We said, “Let’s go into the boat.” It was like an adventure but it was right in our yard, because it had a nice cabin and we fixed it up and I would bring a book and we would have our boom box and listen to a Tigers game or, if it was a rain-out, we’d listen to Beethoven and just talk or plan.

Our life was very magical. People sometimes don’t understand because I was on the cusp of becoming very successful in 1979 and then I left all of that behind.

I was quite happy and I never came into the world hoping to be rich and famous. I just wanted to do something good. In a way, there’s more hubris in what I wanted to do. I didn’t care about being rich and famous. I just wanted to write a great book or do something extraordinary or do something new.

A: I was really struck by words that you attribute to Fred in M Train: “Not all dreams need to be realized.”

P: Yes.

A: Why do you think he said that? Do you agree with that sentiment?

P: Because we had so many dreams. He went to pilot school and he learned to be a pilot and he was a good pilot but we didn’t have the money for him to rent planes to fly. He achieved one dream. He achieved the ability to fly and we sort of daydreamed about maybe someday we do something and maybe he would be able to rent planes or meet somebody that he could share a plane with.

We didn’t suffer because we couldn’t do that. I’ve dreamed of doing a million things that I haven’t done, but I’ve done other things instead. I’ve written many books that aren’t published yet but enjoyed writing them. Fred and I used to make up whole movies that we imagined we could produce or write. Sometimes, it’s just the pleasure of exercising the imagination.

I come from a family of dreamers.

A: Would you say that just being able to dream in that way is an accomplishment in itself?

P: It’s a beautiful part of life that we shouldn’t ignore. I come from a family of dreamers. My mother used to dream about winning the lottery and getting a beautiful house on the coast in New England and we’d all have our own room and she never bought a lottery ticket, but she dreamed about it her whole life. Daydreaming is part of the beauty of life.

I worry in our present culture. I remember going in to a café or walking down the street and people would be in … They would be wrapped in their own thoughts. They’d be going on their own M Train, but now you see people and they’re arguing on the phone or making a business deal or arguing with their boyfriend or having a good conversation, but they’re talking. Then they’re in a taxi and they’re not looking at the window, daydreaming. They’re on the phone and then they’re in a café and they’ve got their computer and a phone.

I look at these people and think, “When do they have time to just dream? When do they have time solely to themselves that isn’t related to anyone or anything, just their own time?” It’s a lot of what writing is, is thinking. It’s not all just you sit down then it all flows to the paper. Sometimes, you have to empty yourself and then the words tumble out, one by one.

A: Near the end of M Train, you write about refusing to surrender your pen and I love that. Would you consider those words a personal mantra?

P: We don’t need a lot of material things. We don’t need a lot of the trappings that we think we need in order to create. We have the external world and we have our interior world and we have nature. Then all we need is the tools of our trade and I think it’s really important that our first thought is to the work. Not where the work is going. I didn’t think of where it was going, how it would end. If it would be a success, if people would like it or hate it after Just Kids. I just got on the train and kept on going until I came to a stop.

I just got on the train and kept on going until I came to a stop.

A: You’ve expressed yourself in drawings, in photography, in music, in poetry and prose, even on the stage. Do you decide the vehicle based on the story you’d like to tell, or would you say the vehicle picks you?

P: Basically, what I do the most is write. That is the most consistent thing I’ve done my whole life, but I think a lot of it is based on how public and how immediate I need a thought to be shared. More political ideas or more global or human concerns usually I express on the stage or through singing, and it’s direct contact with a lot of people.

Probably the most obscure way to express myself is through poetry. I think a lot of where I put my voice has to do with how public my communication is going to be. How physically public. If you’re writing lyrics to a song, you don’t want the lyrics to be as perhaps as obscure, difficult as in a poem, because you want to communicate with people directly when you’re singing them. It really just depends on how much responsibility one has to the viewer, to the listener.

When I was writing M Train, I didn’t think about anything, I just wrote. When I edited it, I tried to think of the reader and if I found myself digressing too far out that it would become incomprehensible, I sort of reined it in, but I didn’t think about anything while I was writing, I just wrote. Then at the end, there’s different things that I edit. Some might be for clarity, but sometimes it’s for rhythm. I’m not saying that the book is musical, but it does have a certain rhythm. Like being on the train tracks or the ocean. The book does have a rhythm and I try to keep that going.

A: Let’s talk about loose ends, because you write that you have always hated loose ends. Is that one of the things that you find so appealing about the detective shows? Can you say more about why you’re such a fan of them?

P: I think the reason I like detectives is I like their obsessive quality. When you have some of these great detectives like Wallander or Detective Morse or George Gently and certainly, Detective Linden. These detectives are all intelligent. They’re all sort of dysfunctional. I always think of them akin to writers or poets. They have all this chaos. They have all maze of ideas and thoughts and they have to make sense of it all. They have to find what’s real and not real within all of these clues or these red herrings and they have to stay on it and they have sleepless nights and they pace the floor.

I watch these detectives, not thinking about the crime, but their objective to get to their punchline, to get their man. It’s a lot like writing. You’re going through all of these pages and all this writing and sometimes the chaos of your own thoughts and you have to rein it in and get your punchline, your last line.

I’m not saying that the book is musical, but it does have a certain rhythm. Like being on the train tracks or the ocean.

I find myself a really lucky person in that I have access to both: I’m able to have these long periods of solitude and do my own work and not depend on anyone. Then I have another whole world where I have a crew, I have musicians, I have people that I depend on and who depend on me. Then you have the people that come and give you energy and then you give them your energy. That’s a beautiful experience, but I’m glad that I have both options, because my natural vent is more solitary.

A: M Train marks the second time you’ve narrated the audio version of a book you authored. Did you learn anything about yourself or your memoir through narrating M Train that you hadn’t been consciously aware of when writing it?

P: One thing in reading it, I was happy to realize that a lot of it is funny. There’s a lot of off-handed humor in the book and that’s how I am and that’s how … I have that in my nature … I don’t know if everyone picks up on that, but certainly, it’s there.

I suppose if I really got down to it and said what I’d learned the most is that, from my South Jersey background, I don’t say my G’s. Because we don’t say ‘em. I can’t do that, at 68 — try to put G’s on my words. It’s just how I talk.

A: Is it strange to read aloud words that you wrote for the page?

P: No, because when I’m writing, I read aloud. When I’m by myself, I read aloud what I write to see if it flies, because sometimes, you can get so writerly. I sometimes stop myself and see how it’s going to sound to the reader or how it might sound in their head. I always do that. I’ve always done that. I pace the floor reading what I write aloud.

A: You’ve experienced a great deal of loss in your life, how do you remain eager to face life’s next challenge, and would you describe yourself as hopeful?

P: I have lost a lot of people in my life. Exceptional amount of people. I do suffer the pain of their loss and I miss all of them whether it’s my brother or my parents or my husband or Robert. All of these people were extraordinary and I feel quite privileged to have known them and I know a lot about all of them, and so I think of myself as a harbor of their memory.

I’ve always done that. I pace the floor reading what I write aloud.

I try to do that memory justice by appreciating my own life and trying to make the best of it. I like being alive. I like being on Earth. We all have a finite time. I just have decided that no matter what happens, just to cherish my life, enjoy it and be a good parent and do my work and appreciate the work of others. Use my voice when I can politically, but I’m determined to enjoy the life that I’ve been blessed with.

Sometimes, it’s difficult to be hopeful, but I’m enthusiastic. I maintain my language of enthusiasm. I love that Jimi Hendrix quote where he goes, “Hooray, I wake from yesterday.” That would be my mantra.