Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly

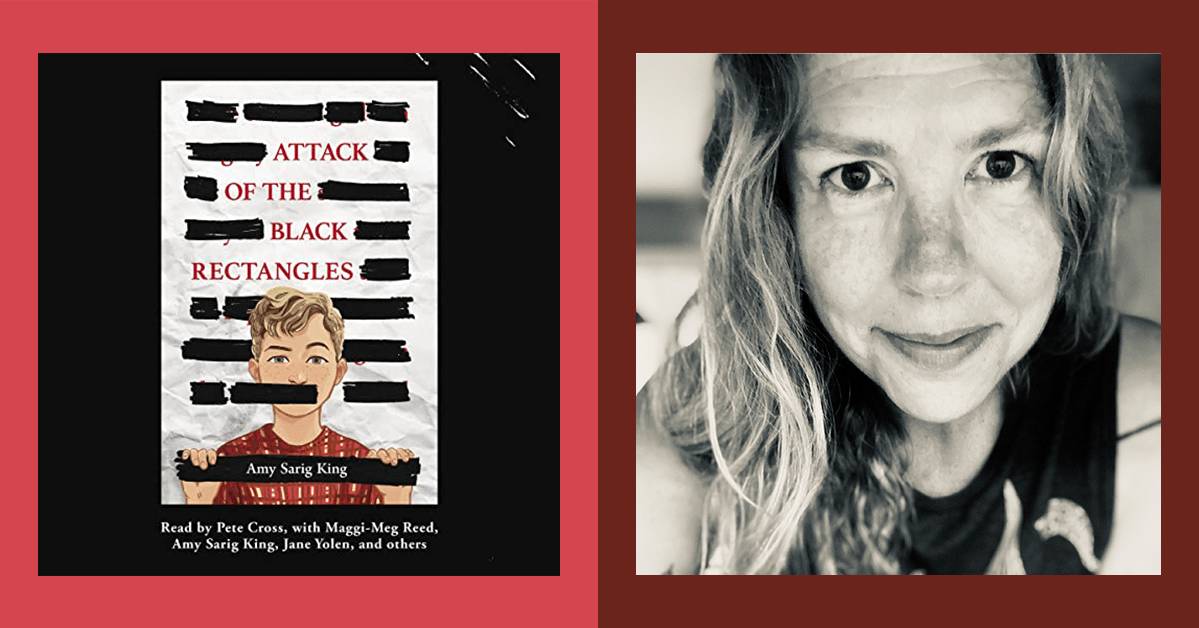

Sean Tulien: This is Audible Editor Sean Tulien and today I have the honor of talking to A.S. King, author of many celebrated books in the middle-grade and young adult genres and owner of a laundry list of awards, including the Printz and LA Times book prize. Her newest listen, a middle-grade title called Attack of the Black Rectangles, is about as timely as it gets, addressing censorship in schools as a trio of sixth graders stand up for the unadulterated truth. Welcome, Amy.

A.S. King: Thank you for having me, Sean. I'm really excited to be here.

ST: Yeah, me too. It's our pleasure to have you. First things first, where do you keep all your awards?

AK: [Laughs] They're around. There's some behind my head here, you can see that. I keep them on a bookshelf in my bedroom because I felt like keeping them in the bookshelf in the living room was too weird.

ST: I get you. One thing I really love about your writing is the complexity and the humanity of your characters, especially when it comes to who might be the closest thing as an antagonist in Attack of the Black Rectangles, Ms. Sett. There's a quote that Mac says that I thought was really, really beautiful and encapsulates this well, which is “Yes, Ms. Sett is a pain and thinks we shouldn't eat Cheetos, but also yes, she was nice to me when I needed it most. No one is ever just one thing.” I was wondering if you could talk about that a little bit in terms of how you are so good at providing humanity even to the characters that might be behaving badly.

AK: No one is ever just one thing, even if we are the people trying to fit into that one thing [laughs]. The more we explore the world, the more we learn about the world outside of us, hopefully the more we grow and change. When we look at the antagonists in our lives, we're often asked, “What do you think caused them to be that way?” I'll go back to an interview I did more than 10 years ago. I'd written a book that had an antagonist who was very violently bullying the main character and a person asked me “But why, and did you show that side of that character?” And I said, "We made a choice not to because it doesn't matter. What's being centered in that particular story was the plight of the bullied, not the bully."

I always want to understand the other side. I grew up in a place where I was surrounded by people who had ideas that were just so completely different from mine. That didn't grow a hatred, it grew a curiosity. And so I like to inject that curiosity back in, and I think with Ms. Sett, this is a professional who's been in her job a long time, but she's also been in the town a long time. So, it's nice to figure out all the different sides.

ST: It makes the whole experience feel full. She clearly does care about her students even if her efforts are often misguided. I think it's [also] evident in Aaron, who, I wouldn't call him a bully, but he has some bullying tendencies in the story, and he still has this well of humanity that he eventually draws on.

AK: We tend to act like the people we hang out with. I've been talking to teenagers specifically about this for a decade or more, and to ask them to look at those five people that they spend the most time with. But what I find as well is that when you see kindness or understanding or curiosity modeled by the people around you, it rubs off. The same goes for hatred. The same goes for nonacceptance. This is the time of life that we're trying to figure out who we are. And it is a time we make many mistakes. I've met many people who were bullies in school but realized that for whatever reason, it was either the people around them or the messages they were getting, but their minds expanded, which is always what we're looking for.

ST: That's actually one thing that really stuck out to me about Mac, the central character in the story. There's a very strong sense of him being a thinker. And I really appreciate that because his way to reflect on the things that are happening to him and the way that he's responding is so pivotal. Like, adults these days might be in some cases not using that skill as much as they should. The fact that you're presenting that for kids is wonderful. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit more about how curiosity is important.

AK: I'm glad you brought this up, because I just had a conversation with my teenager recently that has to do with this. I think that adults are often in little bubbles. I admit this fully. I'm actually in quite a large bubble. We have a very carefully curated world. The older we get, we can curate that world; we can surround ourselves with only the things that make us comfortable, et cetera. Young people have to go to school. I am coming up talking to my now-sophomore in high school where I say, "Oh, I don't like that you have to hear these things." And he's like, "Mom, I hear this... I've been going to school this whole time. You know, you don't understand, there's all different kinds of people." Of course, I know all different kinds of people too, but I have been in a really sheltered space. The difference in education and what young people are learning in school now compared to what I learned in school in the '70s and '80s, there's a massive difference in information and how it's taught.

Like, I had never been educated about Native American cultures. I was handed the same story year after year that wasn't true, and when we say wasn't true, that means leaving out huge parts, like pretending things didn't happen, right? The way that Mac talks about kicking things into the long grass. So it wasn't that they were miseducating us so much, it was that they were leaving out the parts that they felt we couldn't handle. What that did was, it raised generations of ignorant adults to those particular things. So when I think about young people in schools now, they are far more exposed to so much more information in the school, in their books, and in their lessons in fiction, which is a wonderful vehicle for history—and we'll get into that later when it comes to Jane Yolen's book, The Devils Arithmetic—but then they also are learning the pop culture, the parlance of our times, all of those things, they're learning how to look at the world.

And I think that's important to note, that they're not just learning that from their teachers, they're not just learning that from books, they're not just learning it from lessons—they're learning it from the people around them. Our job as adults is to model for young people.

I love how black-and-white we are, often, as adults. “These things are positive, these things are negative.” It's interesting when we start to examine what happens when you take away the voice and the agency of young people, that underestimation that undermines them. And that creates a mistrust between adults and young people.

ST: I guess the saying is "curiosity killed the cat." It should be maybe "curiosity helped the cat grow, even if it was painful" [laughs].

AK: That's true. I mean, it's true. I've been doing this 28 years now. I really can see why I write, and I can talk to young people about why I write. And I wrote because I was curious, but usually it came from being angry or even being angry at myself because I wasn't being as compassionate toward another person. So I am a humanist in that way. And so to answer kind of the first part of your last question, humans are fascinating to me. I am fascinated by them. And I'm fascinated especially by the ones who want to control other people.

"I wrote because I was curious, but usually it came from being angry or even being angry at myself because I wasn't being as compassionate toward another person. So I am a humanist in that way."

ST: Right. And you talk about anger a little bit there. One of the answers is to respond to anger unpleasantly, which there are some examples of in this book. But also the idea that it can be an impetus to positive change, like this idea of hope that we can have for the world, which I think is very evident in this. You specifically mentioned Jane Yolen's The Devil's Arithmetic, which plays a central part of the plot of the story. And I'm not gonna go into details to ruin it, but you also talk about this a little bit in the afterword. I'm kind of curious as to why you chose The Devil's Arithmetic and why Jane Yolen.

AK: This story, the specific book, the specific lines that were censored and the specific questions that that brought to the young people in that situation came from real life. This happened to my kid in 2018. My son came home, fifth grade, I was up in my office and I'm like, "Hey, how was school?" "Oh, it was good." And then eventually he said, "Hey, there's some words crossed out in this book." And I'm like, "Oh, some kid probably just did that or whatever." And he goes, "No, it's Sharpie and all of our books have it." And I said, "Bring that book to me right now." And so he did, and I took these two photographs of the two pages that were crossed out. And I went on to Facebook as one does. And I said, "Hey, anybody got a copy of this book lying around?" And somebody had one inside of a minute. I just posted them and the librarian wrote back, “These are the two areas [that were crossed out] and this is what they say.” That turned into a real interesting Facebook thread just with other people's opinions.

Then I wrote to the principal of the school and just said, "Hey, um, this isn't cool. Let's talk about it. Let's find out how, why, where, what, where this decision was made."

ST: It's such a good visual, this idea of the Attack of the Black Rectangles, like these little black rectangles, these Sharpie-outlined, eliminated parts of the whole text. It's interesting that this actually happened to your kid. I know it happens, but it's still shocking to me. I cannot believe it still happens to the level it does.

AK: Yeah. I saw it. I was a little shocked and until we got to the bottom of at least the who and the why-ish, the ideas that were told to me was that this will cause giggles. It's important to note that The Devil’s Arithmetic is an unbelievably wonderful book. It's a really beautiful way to learn about the Holocaust if you haven't learned about it yet, or to explore it further. And more importantly, to see the plight of the Jewish people, in Poland in this case. So, the fact that these two particular lines were crossed out in the middle of a harrowing scene. In fact, I would consider one of the most difficult scenes in the book. The irony of that decision-making—that this is a really hard scene, it's going to require conversation, which is what teachers do, right? But why this line? Well, “they'd giggle.” Because it's a body part, right?

And it's sort of like, well, how far did we really think about that? If we can read about this terrible scene and all these box car scenes that got us to the scene and all these terrible things that happened, that really happened. And so a child is reading this and taking this information in, as many of us did, to learn about many terrible things. Why would you be concerned with this and why wouldn't you be more in a place to model mature behavior? If someone giggled in my classroom about this, I wouldn't shame them as much. I would more just ask them another curiosity question, which is, "Well, wouldn't you have done the same? Why are you giggling?" And show them a mature way to deal with things like that. It just seemed an ironic book to choose to cross out these specific passages.

Fiction is some of the best education you can get your hands on. Inside of a book you can learn hundreds of things, but more importantly, you can also learn how other people live, what other people went through, and all these things. So, really, it's a matter of an uncomfortable truth, or an uncomfortable job, let's put it that way, as a parent.

Look, I'm a white lady. I can't imagine what it's like to be a person of color with a very young child who asks, "Hey, let's talk about our family tree. We're doing a family tree assignment in school. How far can we trace our family back? Where are we from?" Well, I knew I was German and something by the time I was six, what do we say to young African American children? And do we ever think about the conversations that go on in their homes? Those are difficult conversations that, again, bring in a harrowing truth, but they cannot avoid that.

And the fact that we can seems a little weird, considering it is a giant part of our history, and we still travel with the trauma that it caused all of us in this country. The reason that this is happening is because I believe we haven't faced the trauma, accepted what happened, and moved forward. The only way you can move forward is with the truth. If you don't face the trauma and you can't be honest about it, then you can't actually move forward. That means you can't heal.

"If you don't face the trauma and you can't be honest about it, then you can't actually move forward. That means you can't heal."

This is what I say to teenagers. This is why I go into schools. I talk about this. At my age, when you're in your fifties, when you're in your forties, this is when the trauma that you've been running from trips you up. We're all conditioned to “suck it up, snowflake,” you know, and all these things. And it's a bit like, "Wait a second, this is real stuff." And then if you look at the history and we look at our country, we can't really move forward until we go, “Oh yeah, this happened.” "Oh, our people did this, right." I think about German education in the '50s and '60s after the Second World War, after everything came out about what had happened in extermination camps. And I know people who were educated in Germany at that time, and they did not have a problem telling the truth.

And that meant you had to look at your grandfather differently. That meant you had to look at your father differently, yes. And hopefully those adults were also modeling for you how to forgive themselves, how to understand what happened to them and their minds under that rule, et cetera. And so we have a real problem with that here. I would venture to guess that it is sort of the underlying system of white supremacy and just sort of a protection of the colonizers. I understand that, but at the same time, it's time for us to move forward.

ST: You bring this home in a really personal way in the story when Mac is, I don't want to ruin the details, but I'll say that Mac's father has some mental health issues. And it creates some trauma with him and his mother. And the way that he thoughtfully addresses that in the space that his mother—who he talks a lot about being graceful, which I want to talk to you about too—is very interesting. And his grandfather, who is a positive male role model in the sense that he's trying to heal from his trauma as well, from the Vietnam war. That dynamic is super interesting to me, because you can tell in Mac's monologues, in his thinking, that he wants to avoid those pitfalls, and the fact that the adults in his life give him that space seems to make all the difference.

AK: Violent or abusive people do that because of their mindset. Absolutely. And so that comes again from our groundwater, that comes again from the foundation of the systems that are in place here. Mental illness is often thrown around as a reasoning or an excuse. And in this case, it wasn't one. As that character unfolds, we can see kind of how manipulative he is.

ST: Right, that makes perfect sense to me because it's clear that there's very little self-reflection going on in his father's idea.

AK: Yeah.

ST: Like, whenever Mac brings up an idea that is threatening to his perspective, he reacts with anger.

AK: Yes.

ST: I love that Mac, because he's a smart kid, but also because of his grandfather and his mother, is able to reflect. And even when he does get angry, he's like, “Well, that probably wasn't the best response to that situation.” And he specifically cites because "I don't wanna end up like my dad."

AK: I think that's an important thing. You know, I meet a lot of young people who are walking through things. Sean, we have such a wonderful Norman Rockwell drawing of what a family is, and families are so much more than what we see in these representations. The problem is, of course, we carry those little paintings in our heads. And what happens is, when our families do break, and many, many do, it's almost like we can't mourn the reality of what's happening. Instead, we often go within and we're like, “What did I do?” Or “I'm a freak” or, you know, a million other things. And I meet a lot of young people who feel very isolated because they don't fit that family norm.

I think we often forget, willingly, what young people actually navigate. There are young people in my community who have lost their parents. I know many young people who lost a parent. I know young people who've lost a sibling. It's our responsibility to face those things, and this is where fiction comes back in again. If you've read something like Jane Yolen's book and you understand something like the pain of living through or dealing with the Holocaust, in this example, then you can better face "Oh my gosh, so and so's brother died. What can I do?" You become a more empathetic person.

That's been said about fiction for a long time, but it also makes you not run away from it. And I know adults run away from it. And then also want to keep their children away from it too. And what it really does is it removes the child from the community grief that's happening at the time. And therefore they don't get to experience that. They are then more of an outsider than inside. So again, if we're protecting young people, are we protecting them from life? Because things will happen in the future. Terrible things happen. Tragedy is a reality, you know.

ST: It seems to be the common thread in books that do get banned is that it's something that parents want to "protect" their kids from. And I do air quotes there because it's not really protection, it's more they don't want to deal with it, and they think that that's the best outcome. How would you feel about some of your books, including some of the YA books, being labeled as subversive? What does that word mean to you when it comes to things that you've written? Is that a good thing? Is that a bad thing?

AK: I would consider it a good thing. It goes into the curiosity, right?

ST: It's important to me because I feel like I can mark points in my life where I read a book and it influenced me and it gave me perspective and it was central to me. Like, the first time I read Kate DiCamillo's The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane was the first time I read a kids' book and I knew I was sold for the rest of my life, that was gonna be my career. The idea is that it covered grief in a way that wasn't condescending to kids. And you do that so wonderfully. You tackle these big subjects, these difficult things. That balance of tackling these big issues in a way that is not more than a kid can handle, it's such an art form. But as you said earlier, kids can handle a lot more than adults think.

AK: Kids can handle a lot more than adults, period. I still can't navigate TikTok. Kids are very aware of everything going on around them. And don't you want them to be? First of all, I think that that's a good question. Don't you want them to be asking why, and hopefully don't you want them to be understanding or trying to understand whatever the other side is? We've gone very black and white. But I do believe, and I've said this more than once and I really won't back down from it and I've been saying it for decades, because people ask, "Why do you write for kids? Like, would you write a real book for adults?" I'm like, mm-hmm, you haven't read my work. But when was the last time you talked to a teenager? These are capable, intelligent, resourceful, resilient human beings. And when we take anything away from them because we think they're too young, it takes away that resilience, it takes away all of those wonderful things they're modeling for us.

"When was the last time you talked to a teenager? These are capable, intelligent, resourceful, resilient human beings."

I prefer to write for the smartest demographic and the most curious demographic in our country, and that is our children, and our teenagers especially. I prefer to work with the people who still know how to do algebra [laughs]. How could I underestimate such an unbelievable group of people? I find generation Z inspirational every day.

ST: Yeah. Like, when I do get on TikTok, I will see these 15-, 17-, 18-year-old kids talking with a level of fluency and vulnerability about mental illness that was not afforded my generation. And part of that is because they are subjected to so much more stress and exposure than we were. But also because they seem to be addressing it much earlier, in a much more healthful way.

AK: Well, they have little computers in their pockets. On top of it they have compassionate concern about each other. They talk to each other. You know, I remember some of the conversations I had with my daughter about her friend. She would come home, “I'm concerned. I think maybe they have this” and she'd be, like, kind of diagnosing. And I would immediately go, "Whoa, back off the diagnosis." But what actually happened was she helped her friends. That's actually what happened.

One of the things that Mac gets into, and his grandfather really models this for him, is what I think is at the bottom of a lot of what we're talking about today, which is shame. We walk with shame for things that were done to us a lot of time. But you know, to eradicate shame or to call it out or to pull it into the light, just shame generally, and to talk about what it does to people, how secrets cause shame and this sort of stuff, it's really important for young people to hear this because so often we shush our kids. We tell them to push it back down or “that wasn't a big deal,” that kind of thing. So, I think that that openness with emotion and compassion and self-compassion, and granddad modeling for Mac self-compassion and full honest-to-God truth, like real-life “Hey, you can't get through this unless you say it out loud.”

ST: Yeah. That was one of my favorite scenes in the book, that conversation between Mac and his grandfather on the street was amazing. It'll stick with me for a long time. It does bring one thing to mind, and specifically in how Mac views his mother. The concept of grace comes up over and over again. It feels like, in addition to what you just said, grace is an essential component to that process. Could you talk a little bit more about what grace means in Attack of the Black Rectangles?

AK: It came out naturally, just because Mac had this level of maturity at his age, probably because of what he had been dealing [with] and because he's had grace modeled at home, because this difficult dad was coming around since he was eight. So for the last four years he's been watching his mom extend grace. He watches his grandfather extend grace, and he has to extend grace. He has to sit there and work on this car or whatever with his dad once a week while his dad doesn't speak to him, you know, but pretends that this is great bonding time and all this. And so the best you can do with someone you can't change and someone you're scared of—[his dad] doesn't hurt anybody else, just the people that are easy to hurt and control with [anger]. But the amount of grace that [Mac’s] already been practicing, it came as well from the fact that mom works in a hospice and grief care. There are people right now dying from diseases in these places. And these people are taking care of them and this is what they do.

And I couldn't come up with another word other than grace. That's just so much grace. In times like this, in this world where these young people are growing up in, in what they think has always been this divisive. They don't know about the aisle between politicians, where politicians used to meet. They don't know about any of that. It's just so sensational and so divisive that it was nice to remind them that in life and even in conflict, you can extend grace.

ST: Yeah. There's a great example of grace too. When Mac writes Jane Yolen and Jane writes back to him, and I specifically love the treatment in audio where she is reading that letter response to him. And it's so full of grace. It's such a wonderful moment.

AK: I can't lie, Sean, I've yet to listen to it without absolutely sobbing. There's something about Jane's voice. There's something about her body of work and her service to young people for this long.

ST: Yeah. Something like 400 books, right?

AK: Yeah, more than 400.

ST: Wow.

AK: She's a stunner, when it comes to everything I know about her and her work. It was kind of interesting having her into it. It was very meta. And then I said, “I'm putting words in your mouth and this feels uncomfortable, so I'm gonna bounce it off you."

I actually just played it for my son about two hours ago and he sobbed. She has had her books not just censored, she's had her books destroyed and then one of them burned on the steps of the Department of Education. I'm so grateful for her for finding time to do that for us. That was really cool.

ST: I'm sure at some point there's gonna be an up-and-coming author that wants to have you play a similar role in their story too, because as much praise as we heap upon Jane Yolen, it's all deserved. So one thing I want to ask you is, you had a period where you did quite a few YA novels and now you've done a couple middle-grade novels. What phase do you think you are in, and what do you think is next for you?

AK: Great question. At the moment, I was really blessed to win the Margaret A. Edwards Award for lifetime achievement this year. And when I did, at that point I'd already been trying to work toward early readers. I'm working in that direction. I wrote eight novels over 15 years before I got published. So, actually, I have 11 novels in the attic behind me. And they'll never leave the attic. I don't want you to ever see them, ever. Except the very first one's really interesting because it was all on a typewriter.

ST: I hope that someday somebody gets to see it in some form, if you're comfortable with that.

AK: I'm slowly boxing it up, Sean. I was chased for years to start sending stuff in, but yes, I will be doing that. But anyway, where I'm going, I'm going wide. I'm going back to science fiction in spots. There's a really cool anthology called Tasting Light coming out from MIT Teen Press in October. I have a piece in that. And that really reminded me of how much I like writing weird science fiction. I really enjoyed that because that's hard sci-fi, so it's great. But I think I'm just about to just go wide. At the moment I love short stories so I'm working on a good few short stories. I have a few tricks up my sleeves that I can't tell you about right now, but there's some surprise announcements coming up when it comes to short stories and things like this.

ST: I know I will be listening and reading as well. I really appreciate you taking the time with us today.

AK: Thank you, Sean. I really appreciate you asking me. I have become quite an audiobook listener in the last four years. It was really great to be able to kind of say a thank you back to Audible, because that's who got me through the last few years. I've listened to so many beautiful audiobooks, often on recommendations from interviews like this. So, it's cool to be here, thank you.

ST: Well, thank you for your time. And listeners, you can listen to Attack of the Black Rectangles on Audible now.