As a lifelong wearer of clothing designed for women, I am firmly in the #GiveMePocketsorGiveMeDeath camp. I nearly picked my wedding dress based on the presence of pockets alone, and nothing feels quite so insulting as a pair of pants with a fake set of back pockets. (I’ve ripped many a seam only to discover deceit.)

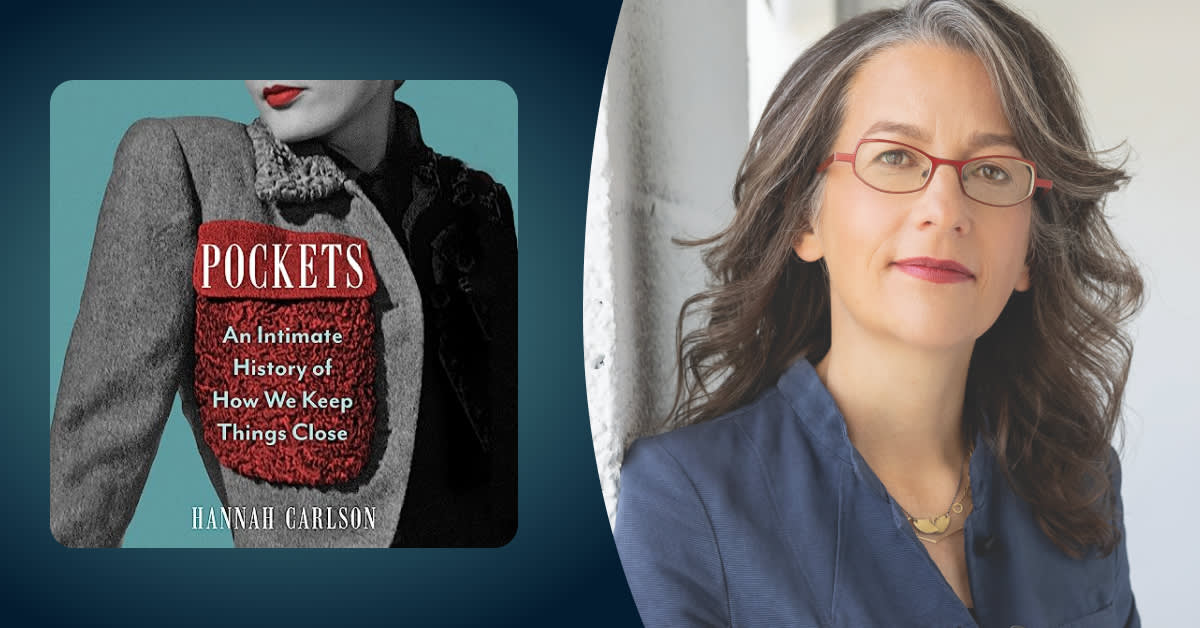

I was, therefore, instantly invested in this little slice of social science from Hannah Carlson. But as it turns out, you don’t have to be a self-described fashionista, follow the latest runway trends, or even have much of a preconceived opinion about the humble pocket to find something fascinating within Pockets.

Hannah was kind enough to answer some of my questions about her inspiration behind this book, as well as her entry into fashion history itself—and why anyone who gets dressed in the morning should care about the stories behind the clothes we wear.

Audible: We’ve been talking about pocket inequality—why men’s clothing seems to have more abundance than women’s—for some time now. But that’s just one of the many surprisingly fascinating aspects of the pocket that this title explores. What was the spark that inspired this deep dive?

Hannah Carlson: I found myself milling around on the street after an unexpected office fire drill and realized that I couldn’t make a phone call, couldn’t buy a coffee. You name it, everything I needed was in a bag draped over a chair somewhere back in the building. I made that patting-yourself-down gesture—the one you resort to after you lock yourself out of the house or the car—looking for anything at all useful. It struck me that the gesture reveals a lot about our expectations about being dressed, and that ease, for many of us, is underwritten by a host of personal possessions—those small articles like phones or credit cards or IDs—that allow surreptitious acts of self-care or provide practical and emotional assistance on the go. I wanted to explore just how much of our sense of self-sufficiency is contained by this array of concealed compartments, by these indispensable companion pieces.

You trained at the Fashion Institute of Technology, have a PhD in Material Culture from Boston University (go Terriers!), and now teach at the Rhode Island School of Design. What drew you to the world of fashion and design?

Early in my career, I owned up to the fact that I didn’t have the hand-skills to be a conservator. An encounter with an 1854 couch, spools of decorative braiding called gimp, and a really sharp 5-inch curved needle spelled the end. If I couldn’t work with my hands, though, I could work with people who do, and I could consider the objects they make. Clothes are at once the most intimate and the most public of objects, and I find it very rewarding to examine the ways designers have approached covering our bodies (no easy task—ask anyone trying to set in the underarm of a sleeve). It’s something of a mystery. Makers have only their ability to manipulate the cut and construction of cloth and yet somehow manage to create garments with astonishingly diverse meanings—meanings that allow us to express ourselves and to recognize one another.

In your opinion, why should the fashion layperson be interested in this topic? How does it affect our lives?

Whether or not one follows fashion, everyone puts on clothes and has, more likely than not, sequestered something into one’s pockets for safekeeping, disgorged the contents of one’s pockets in the security line at the airport, felt a squeamish guilt at rummaging inside the pockets of a child or lover, found a convenient refuge for one’s hands when nervous, or been maddened to discover that one’s dress has not a single working pocket (and witnessed the resulting clamor via hashtags like #GiveMePocketsorGiveMeDeath). Even if we’ve tended to take them for granted, pockets are a distinctive feature of clothing. They are one of those familiar things that, upon closer inspection, have a number of fascinating stories to tell about human behavior and the ways we negotiate the world.

What was one of the most fascinating tidbits you uncovered while researching this book—whether it ended up in the final text or not?

Surprising to me was that the pocket’s arrival, somewhere around 1550, elicited so much anxious commentary and reaction. Into the new places “hid about a man’s body” dastardly robbers and highwaymen could now secret small-scale weapons. Reproduced in the book is a proclamation of Queen Elizabeth I that attempted to ban pocket-pistols, as well as a 1584 news print depicting the first assassination of a political leader by handgun. Witnesses remarked that the killer paused as if to reach into his pocket to hand Prince William the Silent a letter, instead drawing out a pistol and shooting him at close range. The attack was widely considered “an unmanly” one for its reliance on a covert weapon hidden in a trouser pocket.

Do you have a favorite listen of 2023 to recommend, and why?

Avery Trufelman’s podcast, Articles of Interest. Trufelman’s seven-episode “American Ivy” series (2022), on the origins and persistence of preppy style, is a tour de force of investigative reporting on the “vanilla ice cream” of clothing standards—oxford button downs and chinos, blazers and loafers. Trufelman takes listeners to Meiji-era Japan, the campus of Princeton University, and civil rights-era protests, demonstrating that this supposedly exclusive, country club style may actually be one of the more accessible ways to look put-together. Single episodes of Articles of Interest in 2023 continue to explore fascinating questions about what we wear and why, from the cultural significance of Cher’s digital closet from the movie Clueless (why don’t we have them now?) to prison uniforms (why aren’t they actually uniform?) to making a better pointe shoe design (if sneakers and ski boots have benefitted from technology that cushions and protects our feet, why do ballet shoes still employ cardboard and glue?).