Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

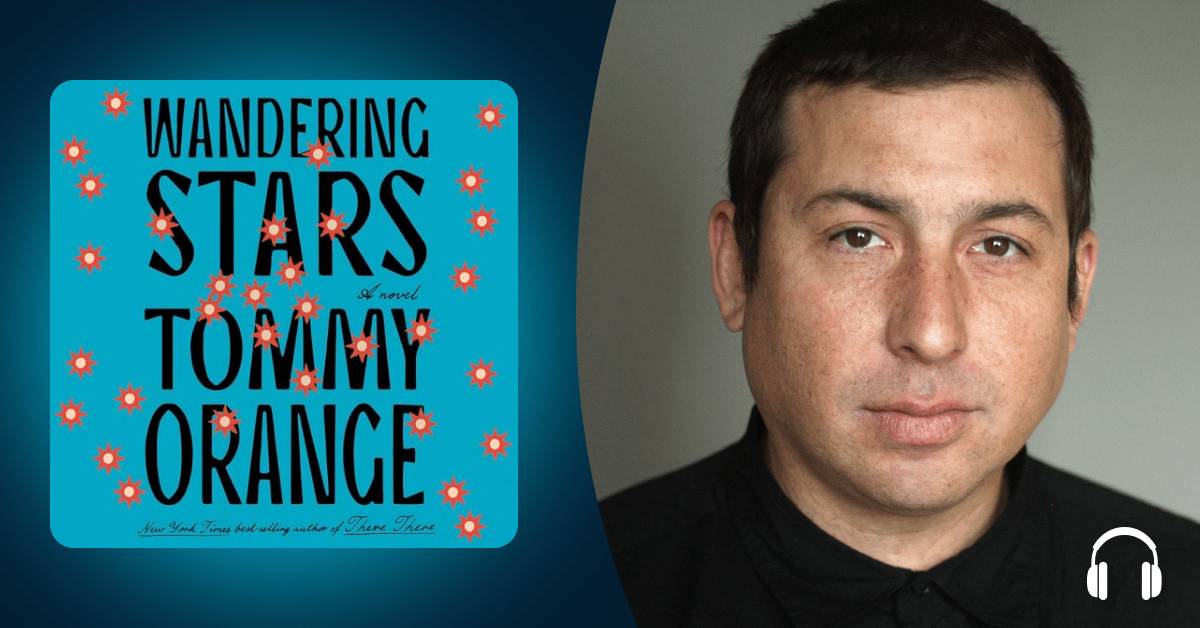

Kat Johnson: Hi, listeners. I'm Kat Johnson, an editor here at Audible, and today I'm thrilled to speak with Tommy Orange on the release of his highly anticipated second novel. It's called Wandering Stars and it serves as both prequel and sequel to Tommy's first novel, There There, which won almost all the accolades that a debut novel can. It received an American Book Award, the PEN/Hemingway Award, the John Leonard Prize, and it was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. It also instantly put the author, who is an enrolled member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, on the map as a major voice in Indigenous literature.

Wandering Stars begins several generations before the events of There There, in 1864, as a Cheyenne boy who becomes known as Jude Star flees the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado. Let's listen to the opening scene performed by Christian Young:

From inside the tipi I thought it was thunder, or buffalo, then I saw the purple-orange dawn light through the holes made by bullets in the walls of the tipi. People outside ran or they died there having been picked off running. Looking back, everything that happened before Sand Creek seemed to belong to someone else, someone I once knew, as I once knew my mother's perfect smile, my father's crooked one, the way both of their eyes looked to the ground when I made them proud, or cut into me when I made them mad. My brothers’ and sisters' way of teasing me about my big ears by pulling on my earlobes, or the way they tickled my ribs and made me laugh until I almost cried in that way that made me hate it and love it, but hate it.

KJ: I love this scene because I think you are a master of weaving together action and interiority so seamlessly. Tommy Orange, welcome to Audible and thank you for this wonderful novel, Wandering Stars.

Tommy Orange: Oh, thank you so much for that very specific compliment about weaving action and interiority. It's very much something that I try for.

KJ: Yeah, you are a master of that, and I think this novel does that so well. I want to talk a little bit about the historical element, which is what opens up the novel. Because unlike There There, which is a totally contemporary setting, this takes us back several generations, starting with the Sand Creek Massacre, which we just heard about. I'm curious when and how you decided to return to the world of There There for this novel, and then how you arrived at the Sand Creek Massacre as the starting point.

TO: Sure. So, there are two very specific moments where I started writing the sequel and when I started writing the historical part of the sequel. In March of 2018 I was actually signing copies of There There at a warehouse north of Baltimore. And the sales reps that were helping me sign had put on a Spotify playlist. And the root of that was “There There” by Radiohead. And the song “Wandering Star” by Portishead came on, sort of like ’90s alternative, and I don't know why but in that moment I knew the book was going to be called Wandering Star or Wandering Stars. I didn't even know at that point if the title was plural. But I just knew, and this is again a mysterious thing, but I just knew I was going to write the sequel and that was the name. And I started writing into it immediately. But it stayed contemporary. It was all the aftermath of the powwow. That's what I wrote into for the next nine months.

"The way that I write is very inside first and then outside."

And then the second moment that I referenced, I was in Sweden for the translation of There There. They invited me to a museum because there was some Southern Cheyenne stuff and they were very apologetic about having it, but also like unsure about what to do about having it, just explaining what's happening in the museum world around repatriation and acknowledging that stuff was not gotten in good ways a lot of the time. There was a newspaper clipping that had Southern Cheyennes in Florida in 1875. And so basically I went down a rabbit hole because I knew Southern Cheyennes were never in Florida. And so it made me wonder why we were there. And I found out that was the origin story for the boarding schools, which is a really devastating part of US history, Native history. And so the fact that half of the prisoners there were Southern Cheyennes, just the fact that my people were in this crucial part of history, just fascinated me.

And then I was doing research around what it was like at the prison castle. And I already started a narrative that was historical with a character named Star. And I saw a list of the prisoner names and one of the actual prisoner's names was Star, and another was Bear Shoe. And I immediately was like, "Oh, that's how I'm going to tie these together. It'll be a family line that starts here and ends up in the aftermath of There There.” It took a lot of work to try to figure out how to do that. But that was when I knew, and that was when I knew I was going to write this historical piece in.

KJ: Wow, that's so smart. And it's funny because “Wandering Star,” the song, was my background with it, and then I didn't know it came from a Bible verse and that they actually quote that verse even further in the song. It really does tie together so well. And then there's the star shard, which is actually the bullet that [Orvil Red Feather] still has in him. And the religious element of the Bible verse is thematically so important too, right? Like, your characters have a complicated kind of relationship to Christianity because of this process of forced assimilation. So it's amazing that you came up with that first and that it all tied together as you were doing it.

TO: I know, I know. It's a very strange thing, and I didn't even really think about it until I started talking about the book more recently. I never questioned why in a single moment I would be like, "Oh, that's the name of the next book." And then to have all these things organically work, like you said, thematically, and tying it into There There. It felt like I'm sort of being helped from the outside somehow [laughs].

KJ: Yeah. That's really interesting. And we’re speaking about the prison castle. After the scene we heard, Jude Star narrowly escapes this event and he's wandering around for a while looking for his people. Then he's taken prisoner by the US Army and sent to this prison castle in Florida. Then, a generation later, his son Charles is sent to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which is run by the same historical figure, Charles Henry Pratt, who ran the prison castle. And at Carlisle, this horrible assimilation of Native children is justified in Pratt's mind by the idea that this is a tool for their survival: “Kill the Indian, save the man” is what’s quoted as his ethos. How did you approach this element of this story and tease out these really personal perspectives that we're getting from the different characters as to how this forced assimilation happened?

TO: Yeah, so I read a lot from the time period, everything I could find about Carlisle and about Pratt. There was a lot of letters that went back and forth between Native people and Pratt. The way that I write is very inside first and then outside. So, to convince myself to keep coming back to the page, I have to write something that feels real and specific to the people that I'm writing about. But in order to convince myself that I can write about this time period, I had to immerse myself in research and to know what is possible in that world. I would write without knowing what actions these characters were going to take. I would write just these interior voices and sort of feel my way to the action and what are they doing and how does it make sense in the story as a whole.

So, there's a lot of groping around in the dark, but having a real intimate relationship with these people just by having given them feelings and thoughts, and knowing that there was this whole Native American church scene, and this character Star—he actually in reality became the chief of police, and I have that happen to him. So, there's little signposts of facts that led me to create action and motivation.

The Native American church has been a big part of my family's life. My parents met in a peyote ceremony. So I did a lot of research about that, and I was very surprised to find out how recent people have been practicing peyote ceremonies. It came from Mexico around this time period. And when you go to a ceremony, there's very much this idea that we've been doing this for thousands of years, and it's just not that old. And so the Jude Star part is very much leading toward this scene where he ends up leaving, and this is why Charles goes to the school. It's all around him trying to figure out his own meaning. He drinks too much and goes to church to hear people talk about God, and he is trying to figure out how he feels about God and Christianity. So, all of these things, I find what I can write about personally, because I was raised evangelical Christian but my dad was a Native American church roadman. And so there's a lot of interior stuff that I can write into that pulls from a very personal place.

KJ: Yeah, the peyote stuff is so interesting. One thing I saw woven through a lot was this idea of medicine. Medicine can be drugs, it can be for good, or it can be for addiction. And it did seem like the peyote and psychedelics can be really helpful for people getting out of addiction. But then there's medicine and pills that people become addicted to. It's like religion. There's the good and the bad, I guess.

TO: Yeah, there's a conversation that Charles Star has with Opal at one point that talks about intoxication and he's sort of claiming that intoxication is intoxication no matter what you want to call it. And so there's a lot of calling into question what is the nature of medicine and addiction, and where is the line blurred?

KJ: Yeah, addiction is definitely a heavy theme of the novel, and obviously been an issue in Native communities, but also our society at large suffers hugely with addiction. All of us have been touched by it, I think. And to use a word that one of your characters really hates, I feel like this novel is full of wisdom about sobriety and recovery that people will find useful. I really did feel like, "Wow, there's a lot in here to draw from." And addiction can be hard as a plot line. How did you handle this theme of addiction and this heavy topic?

TO: Well, it's just been such a big part of my life, my family's life, for way more years than it hasn't been an issue. Without going into too much, because it's not my information to reveal, but just my family has an intense history with addiction and I've had struggles myself. So I'm writing, again, I'm writing from a personal place. It's a really tricky subject. I think there's a lot of narratives out there that are just, like, recovery is the happy ending. I haven't seen enough addiction narratives that go into the complexity of why people end up with addiction. I think recovery is important, and I'm very happy to hear that you think that there's useful stuff in here because I think people that suffer from it themselves or that they have family members, it's a really brutal thing to happen to you, to be in your life. So, I appreciate you saying that there's useful stuff because sometimes with fiction it's hard to point at stuff that's useful.

"What is the nature of medicine and addiction, and where is the line blurred?"

KJ: It is. And I'll say I personally don't drink anymore, so I've been sober for five years, and leading up to that time I devoured recovery memoirs. That was like my favorite thing. I'd read so many addiction memoirs. And the fun is the person getting in all the trouble and doing all the bad things, and then they recover and everything's great. And with this, I feel like the generational element and the way that trauma echoes is so important. And then also just the day-to-day of how do you keep doing it and the little pearls of hard-won knowledge that people pass through. I think the character of Sean does that a lot. I just think people will find it helpful, so thank you for that.

TO: Thank you. And you talked about how do you handle writing something so heavy, and I think for me it was a way to process a lot of feelings and thoughts, and so it never felt like I was taking on weight. It felt like I was dealing with stuff that I needed to think about and feel. And so I was, if anything, releasing some amount of weight by writing about it.

KJ: Right. Well, I think addicts help addicts, right? Helping someone get through what they're going through is really helpful. And so I think your storytelling is going to be helpful for a lot of people and also for you, I'm sure.

So, I actually had the pleasure of interviewing you before, back in 2018 when There There was being released, and I know a lot has changed for you in that time. How has the experience of releasing this book been different for you? Did you feel a lot of pressure doing the follow-up or do you feel more comfortable with the attention? What’s different?

TO: I must have just looked like a deer in the headlights when you saw me at that point [laughs].

KJ: No, you weren't [laughs].

TO: Yeah, it was the beginning of a really terrifying period where I had to learn how to public speak by just being thrown into the water to learn how to swim, so to speak. There was a lot of awkward, sweaty, nervous talk, like heart-in-my-throat, months of figuring it out. And then for two years I pretty much toured nonstop. It became like the festival circuit or lecture stuff, so it was difficult. And part of it was really great and part of it was really hard, and traveling became very anxiety-inducing. And then we had the pandemic and pretty much everything stopped. And during that time period it was not easy to write.

But the whole time I've been writing the second book, I have felt the pressure after the success happened with There There. I felt immense pressure, because when I was writing There There, there was no audience. The first three years of writing it, only my wife even knew I was doing something like that. And then the next three years, or two of those years, I was in an MFA, and so I had my peers and my teachers were reading it and giving me feedback, but I never had an idea of audience. I just wanted to finish a book.

So, there are a lot of new voices in the writing space. New pressure, new voices, new critics. And to keep in the same spirit of the way that I wrote There There, it took a little more work to do the same kinds of revision and put my sentences through the same level of scrutiny, with the same clarity. It was a little harder to get to it all. I never felt the confidence boost that probably should come with success. I think it's just as common for people to feel crushed by success as to get some kind of confidence boost. The good feelings are very fleeting. And the rest you just have to kind of work through, the new doubt and the new voices.

I have a lot of different ways to mitigate doubt. I run a lot. I listen to robots, or now it's like AI-generated text to speech, which is getting really good. It still has a long way to go, but I'm using one now that I really like and it makes it so that you can change up your work habits. If you're stuck you can go take a long walk and listen, or I run, or you can do chores and listen to your work. Sometimes I drive because I can't do anything. Like, it's painful, but I'm holding myself hostage and making myself listen to my work because I can't do anything or I'll like be in peril because I'm trying to edit the thing that I'm hearing in real time while I'm driving, and that's not safe. So, I have a lot of ways to go around what might otherwise paralyze me. And I've just been gathering tools over the years, and so I'm hoping the next book, which I'm in the middle of writing, will not take six years, because that's how long it took for There There and Wandering Stars.

"I never felt the confidence boost that probably should come with success. I think it's just as common for people to feel crushed by success as to get some kind of confidence boost."

KJ: Can you share any details about what the new book is about or will we have to wait?

TO: Yeah, I think it's a little early. I did sell it already. I am like a hundred pages in and it's not related to Wandering Stars or There There. It's a contemporary story, and that's about all I want to say right now, because sometimes if I haven't written enough yet and I start talking about it, I can lose energy.

KJ: Right, right. I have a friend who said that they have a fake novel that they use for just conversation so that they don't have to talk about the real one.

TO: I like that.

KJ: But that's really smart because, yeah, it can take the air out of what you're doing if you talk about it too much. So just take me back a little to There There, and you mentioned that you worked on it for three years where nobody really knew except for your wife that you were working on this. How long before that were you writing? When did you know that you wanted to be a writer and how did you get started?

TO: I came to writing pretty late. I would say I probably started around 2005, between 2005 and 2006. It was after I graduated from my undergrad. My undergrad is in sound engineering. I was a musician and I very much wanted to score films, like independent films, just quiet films, piano stuff or strings. And there was no easy route out of school to do that. That takes I think years of establishing yourself as a musician, or you know somebody. I don't know the path. And so I ended up working at a used bookstore and fell in love with fiction for the first time.

I really didn't know what fiction was doing. I skimmed books in high school to pass tests, and I didn't necessarily even pass them. I didn't do well in school. I wasn't a good student, at all. I didn't have a lot of readers in my life, so nobody was handing me a book like, “You have to read this” or “This is a voice for you.” I didn't know Native American literature existed. And so I found fiction on my own while I worked at the used bookstore. And I was part-time there and part-time doing data entry at the Native American Health Center. And that was sort of the beginning of me getting to know the Native community in Oakland, because even though I grew up in Oakland I didn't grow up around the Native community in Oakland.

Everyone that I knew who was Cheyenne lived in Oklahoma, and we would go back to visit family. That's sort of what I knew. My dad was never involved with the Oakland Native community. He knew lots of people in it, but that just wasn't his social scene. So I worked the next almost decade at the Native American Health Center. And then after the bookstore closed down, I just wrote and read in private as much as I could. And it wasn't until I found out I was going to be a father, in 2010, and it made me want to take the writing that I was already doing more seriously and to take on a more serious project. Something about the gravity of becoming a father.

And so I came up with the idea for There There in a single moment—again, one of these single moments. I was driving to LA with my wife to go see a concert at the Largo. And the idea for There There, that all these characters would come to an Oakland powwow at the Coliseum, their lives would converge and you would find out how they're connected, and it would sort of end in a cataclysm. All that, like a single seed of an idea that would be a book, came to me in a moment. And so, like I said, then I wrote privately for three years just figuring out if this was something I could do, if it had legs, if their voices felt real. So yeah, that was pretty much the beginning. But becoming a writer happened for me pretty late.

KJ: I think it's so cool that you becoming a father was part of the catalyst, because as a parent, I appreciate [your work] so much because of how bad our US history is on this subject of Native American history. I was listening to the book and I was, on the side, looking at these before-and-after pictures that William Henry Pratt had done with these students at the school, and it was so upsetting to see. And I was talking to my son and he was like, "Oh, we saw those in school." And I was like, "Wow. I did not in school." A lot of this is like new history for me. So I'm glad that some kids are getting a better education, but I feel like this is really important that you're correcting a lot of this and I think this is going to be a way that many people hear some of this history.

TO: Thank you. Yeah, when my son started public school, we were like very afraid of November and the way they would not talk about it or talk about it only as it related to Pilgrims. And we were living in a rural area when he started public school and he came home with this offensive Pilgrim pamphlet. And that year we just pulled him out of school for a week, just to kind of skip all of the nonsense that he would be getting.

And then the next year we were like, “We can't just pull him out of school.” So, we brought a Native family, friends of ours, up from Oakland to this area and they danced for the class because they were powwow dancers. And the guy came up in jeans and a ball cap and a T-shirt and let the kids ask anything they wanted. And he's very charismatic and he kind of corrected a lot of their ignorance, questions like, “Why don't you live in a tipi?” And he's like, "I work in an office, you know, I drive a car." Just reminders, because the only thing that generally is taught is this 400-year-old history and it's around the Pilgrims and it's in November, and we don't get an update unless you have a special teacher or you're at a private school or you go to college and end up taking a Native American studies course or something like that.

KJ: Yeah, it's not good. And then I'm also curious, when you're talking about your writing and how you started writing, to me, your writing style is very specific, but it's also because it's what you're using in There There and Wandering Stars, which are very connected. So, I don't know if this is how you will be doing it for your next novel or what you plan to do. But I do think this multi-perspective approach that you've been doing, to me that's very you and you get into people's heads, like even women and older people in a way that's really powerful. And I'm just curious if you think, storytelling being so important in Native American culture, is that something you were exposed to growing up? Do you think that affected the way that you write or not?

TO: You know, I was just thinking about this today. I didn't grow up with any storytellers. I think my fiction voice really came out of reading a lot of world literature, a lot of works in translation. Like, one of my favorite writers and one of the writers that really made me want to write and find my own voice was Clarice Lispector, who not a lot of non-writers or specific kinds of readers even know who she is. But she's not a conventional writer at all. I'm re-reading Hour of the Star right now. I think there were certain books, fiction books, that made me want to do a multivocal thing. I think that's part of it.

I did digital storytelling work and I did meet with a lot of Native people and help them tell their stories, and that shows up as Dene's work in There There. But I would never say that I was influenced by like a good storyteller, somebody who can tell a good story. I wouldn't say that about anybody in my family or in my friend group necessarily. That's a very specific quality and some people are very good at it. And it really came from fiction and loving when voices feel very real in fiction.

And then, like I said, a certain number of books, like Jennifer Egan's Visit from the Goon Squad and Marlon James's Brief History of Seven Killings, and Colum McCann’s Let the Great World Spin, Louise Erdrich’s Love Medicine—these are all multivocal works and play with POV. Just from a craft level, I loved the idea of playing with POV and getting on the inside of somebody so that when you're reading it, you feel that you know you're getting the inside of a real person. And I just love that fiction tries to do that, that we can sort of try out consciousnesses and the reader can experience what consciousness is like through this exploration of interiority. Movies and TV don't really have the same access to that. And that's part of why I love fiction.

KJ: I agree. It's like very claustrophobic to always be in one consciousness, right? So, yeah, that's very liberating, I think.

TO: I think it's also very like Western canon to have a single hero. And I think there are a lot of people who have heard this sort of hero story so much that they don't like to get a chorus of voices. And I just happen to love that in reading. And I'm not saying that there's anything wrong with the hero single-story thing. That's just my taste. That's what I like to read and so that's what I like to write as well.

"I loved the idea of playing with POV and getting on the inside of somebody so that when you're reading it, you feel that you know you're getting the inside of a real person."

KJ: Right, right. Well, and it translates so well in audio because you have these different actors who you kind of are like, "Okay, I remember this person and I'm with this person now." And Wandering Stars has an amazing cast. Some of them are returning from There There, obviously the same characters. Orvil is continuing, and Opal is also the same actor, but there are others as well. They all do such an amazing job. I'm curious how much involvement you had with casting, and if you had any if you can speak to any highlights of the audio production.

TO: Yeah, I felt very included both for There There and this time around. And the continuation of certain actors made sense because they continued in the book, so anybody reading across both books will have that sort of continuity of voice. And then there was a lot of new voices and I got to have these little auditions. And that was really exciting. To consider if the voices fit the voice that I wrote was a really interesting thing to be able to be a part of. So I was really happy to be included, and the cast is very diverse and I think there's more voice-over actors on this one than in There There, and I like that. I like a big cast.

KJ: Yeah, I agree. And you're an audio guy yourself. You said you listen to a lot of audiobooks.

TO: I do.

KJ: I know you said Marlon James’ Brief History. I don't know if those ones you were naming were audiobooks or just books you love, but do you have any favorite audiobooks that you love?

TO: 2666 by Roberto Bolaño. I read that when it first came out as a real book and then I listened to it and it was an excellent performance. The performance of Brief History of Seven Killings was amazing. But there's almost too many to name. I'm not like a super picky narrator person. I'm not like going to not read a book if I don't like the narrator. And I do dislike certain narrators, but it's not going to stop me from reading a book. There are too many audiobooks that I've loved.

KJ: Clarice Lispector is good in audio too. I feel like you might not think so, but I'm listening to The Passion According to G.H. and it's so good in audio. I love it.

TO: Yeah, there's something incantatory about her writing and it translates really well to audio.

KJ: Yeah, agreed. Over the past few years, and definitely since the release of There There, we've seen a few Native American stories rise to the forefront of popular culture. Not enough, but a few, including obviously the Oscar-nominated film Killers of the Flower Moon, which is not a perfect example, but definitely very high-profile example, as well as the FX show Reservation Dogs, which is truly groundbreaking and very hilarious. Not to make you a spokesperson on Indigenous storytelling, but I would love to hear your thoughts about where we are with the state of Native American storytelling and how you hope that your work is shaping the direction that you want to go.

TO: Overall, the feeling that I have is one of hope. Like you said, Killers of the Flower Moon is not perfect, but Lily Gladstone getting an Oscar nomination is amazing. I think we have every reason to feel excited about a future for representation for Native people. We've had these renaissances happen, after the Civil Rights movement and taking over a prison island and being national news, like Nixon was involved and aware. And then people wanted to hear about our stories. And in the ’90s, again, not a perfect movie, Dances with Wolves swept the Oscars, and it's likely that that'll happen with Killers of the Flower Moon. And all of a sudden people want to hear what's going on with us, they want to see more movies. More books will come out. I think that might happen this time around again.

"I think we have every reason to feel excited about a future for representation for Native people."

So, we're already in the middle of something that started with Standing Rock, at the end of 2016. This newest renaissance, I feel like that's when it started, and I guess we would be eight years in now. And that's I think more than before. So, I think there's a sustainable, building energy around not just Native voices, but like this sort of own voices movement. And the publishing industry is getting more diverse and people are calling for more representation across a lot of different industries.

So, I think we have every reason to be excited. Reservation Dogs was a really groundbreaking show. So is Rutherford Falls. Those shows are gone now. So, I hope this momentum continues and we get a sustainable thing going. There There is currently not in production, but sort of maybe on the way to it. I can't say too much yet. But There There could be a TV show and that's super exciting and it would be obviously like a full Native cast. And there's two writers right now working on it.

I hope that Wandering Stars and my success means more open doors for Native writers and that we get more Native books. And if Wandering Stars is successful, I just hope part of what that means is that people take chances on other Native authors, because that would be like one of the most amazing things that my success could do.

KJ: Yeah. I mean, that's a lot of pressure for you to feel, so I hope you don't feel that. But I think it will be successful. It's a beautiful, beautiful book. And you also have your MFA from the Institute of American Indian Arts, and I believe you are still teaching there?

TO: Yeah, I've taught there since 2017. It's a low-residency MFA, so that means it's like remote learning. I don't feel like a real teacher because I have been kind of busy these past years and I haven't taken on a big load. Like, I'll take one or two students. The most I've taken on is four students. Right now I have one student. So, I'm still teaching and I enjoy working with students. It's a great program and I think there's been a lot of books that have been published because of the program. And I hope more MFAs, Native-specific MFAs, pop up because it just means we're giving Native people access to the publishing world.That's part of what an MFA does, is you're working with published authors. That's like the requirement to teach in an MFA is to have published. And if you've published, you might have some access or you can help people. Even just telling the story of how you got access can be helpful or give hope for people that are trying to write books.

KJ: That's so cool. Tommy Orange, thank you so much for your time today, and congratulations on this beautiful audiobook Wandering Stars, which is available now on Audible. Thank you so much.

TO: Thank you.