Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

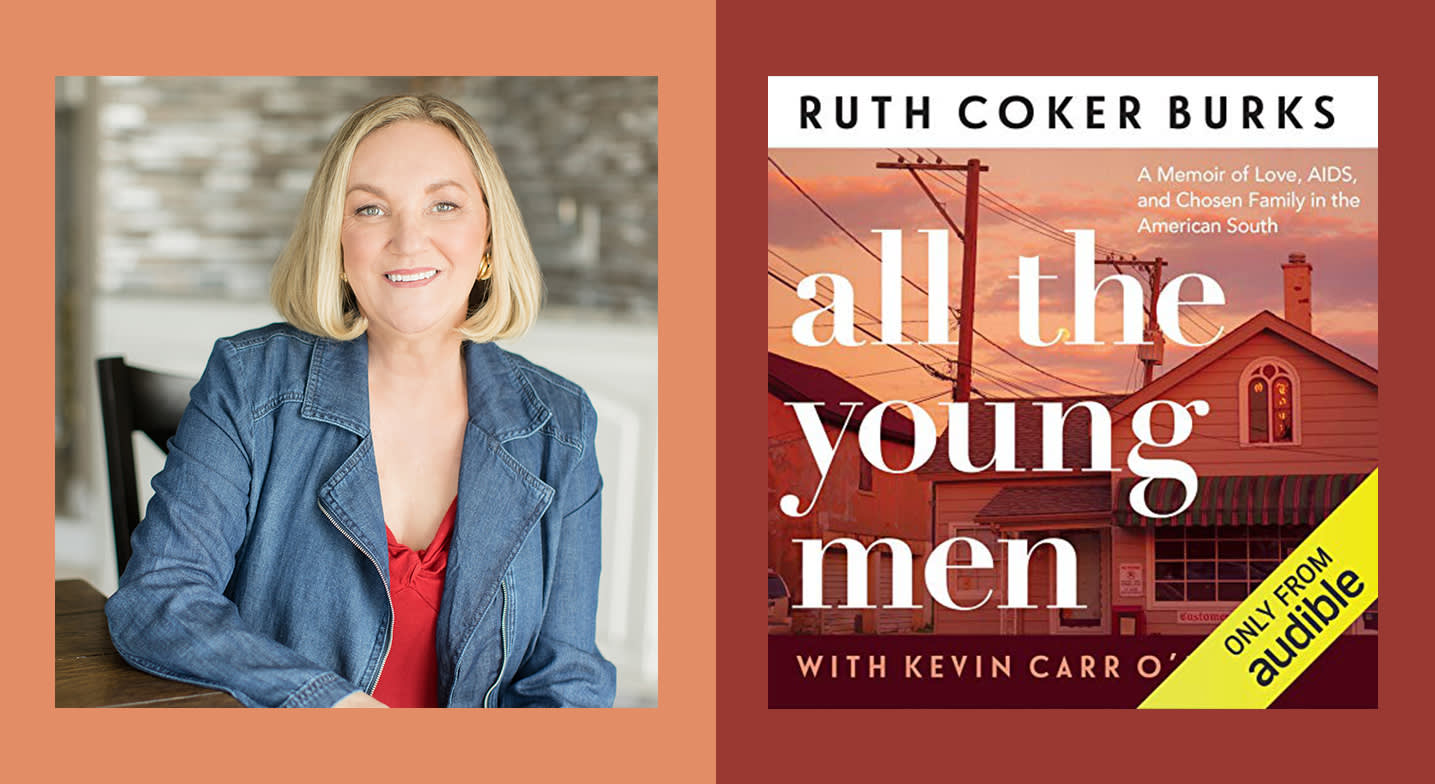

Michael Collina: Hi, this is your Audible editor, Michael Collina. Today I'm honored to be speaking with Ruth Coker Burks, an AIDS awareness activist and caregiver who helped thousands of queer folks in the late 1980s and into the 1990s. She's here to talk about her memoir, All the Young Men. Thank you so much for joining me today, Ruth.

Ruth Coker Burks: Thank you for having me. I'm just delighted.

MC: And thank you so much for all of your amazing work too. For those who don't know Ruth, she's been nicknamed the "cemetery angel" due to her efforts in caring for AIDS patients whose families either abandoned them or just outright refused to be present in their final moments.

Ruth also wound up burying many of these folks in her family's cemetery, largely against the wishes of her local pastors, nurses, doctors, and really the entire community of Hot Springs, Arkansas.

RCB: Right.

MC: Why did you feel that 2020 was the right time to get this out into the world?

RCB: Well, I didn't really think about 2020. I started this in 2014 with StoryCorps and that's how I got started. A gentleman came on my Facebook one night and asked if I was the nurse in Arkansas who took care of AIDS patients. I said, "Well, I'm not a nurse, but I think I'm who you're looking for." And that's how it all started. People think that the AIDS crisis happened on the West Coast or on the East Coast, but they don't think about the center of the country and especially in the South. We're right smack on the buckle of the Bible Belt, and the churches would put so much pressure on these families to throw their gay children out just because they were gay. Could you imagine that?

"People think that the AIDS crisis happened on the West Coast or on the East Coast, but they don't think about the center of the country."

MC: It sounds like a terrible reality that many folks had to face.

RCB: Yes.

MC: And you actually also perform this memoir. Was it important for you to tell this story yourself?

RCB: It really was. I was so thrilled when y'all asked me to do it. I just feel like, number one, to hear somebody trying to fake a Southern accent is just the worst. I wanted to tell it in my voice for that reason, but then also I knew these guys so well. More than most people knew them. And it's a story that is so personal to me and I've kept it quiet all these years, and it was just very important for me to be able to tell the story the way it happened.

MC: So jumping into your life story a little bit more, you met your first AIDS patient, Jimmy, while you were visiting a totally unrelated friend in the hospital in 1986. You saw how horribly he was being treated by the hospital staff and you went in just to sit with him. You tried to reach out to his mother, and ultimately you were there when he passed away and you wound up arranging for his cremation and burial after passing, none of which is an easy task, especially with so much fear and uncertainty about AIDS at the time.

Once word got out that you were willing to help these folks with AIDS, more and more calls and pleas started to come in.

RCB: They did.

MC: How quickly did your scope of work change from just helping one or two people to helping the larger LGBTQIA+ community as a whole?

RCB: I thought that Jimmy was going to be the only one I was ever going to bury. You couldn't get any information on it, period. No one knew anything about HIV or AIDS. And they started calling and all I could do was to make sure they were safe and had a place to sleep and make sure they had food. And then I would meet them the next day. And I would start in on making a mental checklist of everything that they needed. And it was just making sure that they had it. Having that support and love meant the world to these men. I loved these guys so much and I had so many of them and they were all considered my guys. They all loved it when they were considered a part of the family.

"Drag queens are the most fascinating, exquisite, loving, and caring human beings on Earth. They saved us during the AIDS crisis and they have always come out in force whenever needed."

MC: It really warmed my heart just hearing how much love and affection you had for this entire community. They did become a part of your family.

RCB: Oh, absolutely. And my daughter, they took her into their care and their love. Drag queens are the most fascinating, exquisite, loving, and caring human beings on Earth. They saved us during the AIDS crisis and they have always come out in force whenever needed. And I was so lucky that I got to also have drag queens. What is life without drag queens?

MC: Absolutely. I agree with you there. This memoir, All the Young Men, it was also just as much a memoir about your guys as it was your own story and your own work.

RCB: Oh, it was 100 percent. I would never have written this book, this memoir, if I had not found [coauthor] Kevin Carr O'Leary. He channeled my men. It was like they came in and lived inside his head and he brought them back so well I could smell their cologne and it brought back such beautiful memories that are so real.

MC: That’s beautiful. That's so interesting to hear.

RCB: Yeah. It was so important for me to get the story right. I wanted them to be rich and full of life and I wanted them to be, you know, their boy selves and then their drag queen’s fierce selves. And I just wanted everyone's life to matter.

MC: It definitely comes through in the story.

RCB: Good.

MC: As a single mom in the 1980s, you also had to have a well-thought-out approach to your activism. You had your daughter, Allison, to think of.

RCB: Right.

MC: And I'm sure you had the very valid fear that if your work became too well known, you could lose custody of her. You could also lose standing at your church. You could lose standing in the community as a whole. So there was a lot on the line for you.

RCB: I did not know it at the time. It was like God put blinders on me because I knew that there wasn't a judge alive that wouldn't have taken my daughter away from me. But I didn't realize that the community would turn on me and I didn't realize that my church would want me out and that my life would just be different than I thought it was going to be. But it turned out so much better.

MC: With that in mind, being a single mom in the 1980s, advocating for safe sex and AIDS awareness, that's a tough job for anyone, I think, but particularly for a single mom in the 1980s. And here you were in Arkansas, just defying all of these conventions and doing what was right. How did that affect you and your daughter?

RCB: Well, it really affected her. The people in town, the parents would tell their kids don't play with her because you'll get AIDS from her. People were just mean. They were just mean.

"...We were doing exactly what they wanted us to do, but they didn't want us to do it with gay people."

MC: It's such a shame to hear that, and I'm sorry that you and Allison had to go through that.

RCB: You know, we just did. We just did. I would sit in church on Sunday morning and they would say, "Go out and feed the poor, take care of the homeless, take care of the sick." And that's what we were doing. So we were doing exactly what they wanted us to do, but they didn't want us to do it with gay people.

MC: So there was obviously that pushback from the members of your community, of your church.

RCB: Right.

MC: Did you experience any pushback from the LGBTQIA+ community itself? You were a straight Christian woman teaching safe sex and AIDS awareness to the queer community. How did some folks in the community take that?

RCB: Well, they all took it. They were great sports. I didn't want them to think that I was apostatizing them because never ever would I do that. The first time I went into the gay bar, I had on a nice pretty dress and I had this book. And so Paul [the manager of the bar] thought that I was bringing this thick Bible in and I was going to quote Bible verses to him. And when he found out that I wasn't, it made a huge difference. They just knew that they could trust me, and the way I did the safer sex [education], it was funny and it was fun. If you can teach a drag queen safer sex, you're doing good.

MC: Definitely. And you mentioned having a lot of help and support from the queer community and from the drag queen community specifically.

RCB: Yes. We were invited for Thanksgiving potluck and Christmas potluck, and any of the potlucks that they had. If we needed money, because every penny that we made went back out into the community to pay for rent or utilities or medication, they would twirl up a drag show on the weekend and they would raise thousands of dollars. A lot of those drag queens were ill at the time also and dying, and they would still come out and perform. And they needed that money themselves to pay their own rent, but they would give it to us to give out to the patients who desperately needed it.

MC: That’s a lot for any one person to do. How did you manage?

RCB: You just take one step and then you take the next step. We never knew what that was from day-to-day, but that's how you get through life. You just do it one step at a time. My friend Marsha used to tell me, "If you don't know what to do, don't do anything." And there was a lot of not doing anything because none of us knew what to do. It was kind of like, well, I know you came from New York, what were they doing for this in New York? What drugs were they using? And so there was a lot of that also, just trying to find out what to do.

MC: So throughout your memoir, it's been clear that you've pretty much spent your entire life caring for people.

RCB: Right.

MC: First as a child who had two sick parents to help care for, then with your friend Bonnie, who was having cancer treatments at the hospital, and then your guys. Have you always had a knack or passion for helping folks and giving care to those who need it most?

RCB: I think I have. I guess I just kind of feel whole when I'm doing it. I feel like I'm doing something for humankind and I'm doing it for my fellow man. And it's just something that has to be done. I don't know how people can just step over a situation and pretend like it's not happening. And these were young men. I mean, they were 25, 19. They were so young and they never knew what hit them. The first wave never knew what hit them until they were already almost dead. By the time they got to the hospital, they usually lived six weeks from diagnosis until death. And my guys ended up living two years longer than the national average.

MC: I'm so happy to hear that. Many thanks to you for that.

RCB: We all became a big family and we took care of each other.

MC: How do you feel about AIDS awareness and safe sex instruction now in 2020?

RCB: Oh, it's horrible. We have got to go back and start at the beginning and go, okay, this is how you get HIV and this is how you don't. And if we can at least get them, this is how you don't get it, that's a great start.

MC: Has living through COVID-19 brought up any old feelings about living through the AIDS crisis?

RCB: You know, the thing about it is you've got to do what works. The gay men who were dying found out if they wore condoms, they didn't get HIV. If you wear a mask you're less likely to get COVID. Why everyone isn't wearing a mask, I don't know. But back in the day there were men who wouldn't use condoms.

MC: Have you seen any other major parallels between COVID-19 and the AIDS crisis?

RCB: I see the fear that we didn't know whether you got it out of the air. We didn't know how you got it to begin with. I see a lot of that. It's just education, education, education.

MC: Absolutely. Thank you so much, Ruth, and thank you again for all of the invaluable work you've done for AIDS awareness, and for the broader queer community. You've touched so many lives and helped to make the lives of many other people just so much better.

For folks who haven't had the chance to listen yet, Ruth's memoir, All the Young Men, is available now on Audible, and I highly, highly recommend it. Just make sure you grab your tissues first.