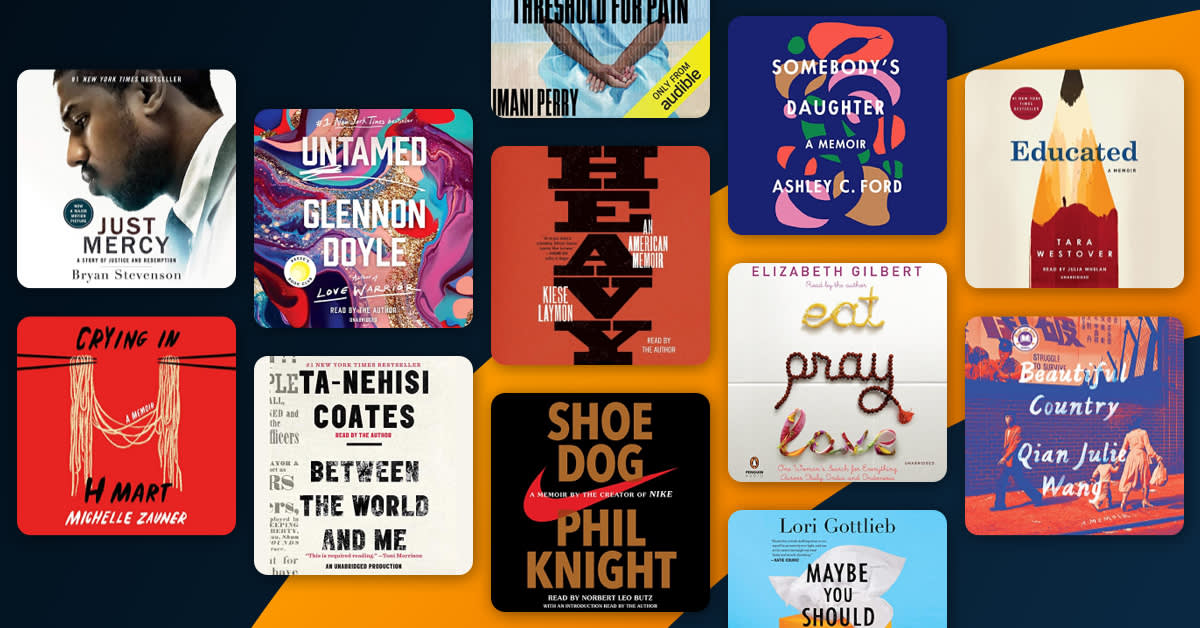

“That’s me. That’s really me,” I say to myself when I stare at the cover of my Audible Original, Quite the Contrary: On Life, Work and Loving Miles Davis. And then I say, sometimes out loud, “You did it!” What a feeling, getting the big “yes” that eluded me for so many years.

Quite the Contrary actually began as a work of fiction. It wasn’t any good, just a bunch of stupid work as the truth was better—it was in my hands, heart, and head. I deleted that version and started working on the nonfiction manuscript.

A good friend, the late Richard David Story, former editor-in-chief of Departures magazine, suggested that I workshop the book. I did, for three years; it was helpful and a great experience but I had to stop. Some of my fellow work-shoppers shared content from the book outside of the group, namely anything that had to do with Miles. One even walked up to my sister at an event and said, “So, tell me what happened between you, your sister, and

Miles.”

No matter how many times the instructor made it clear that everything shared in the class should stay in the class, the chatter continued. I was also the only Black writer in the group and at times the white gaze was overwhelming, and frankly, pissed me off. “Your book reminds me of The Color Purple,” offered one woman. There is nothing in my life remotely near that story, but that’s all the reference she had.

It was time anyway to set the manuscript aside. The luxury of concentrating on writing a memoir no one had asked for didn’t exist. There was rent to pay and a mortgage on a country house I’d bought—but that’s another book, Yvonne Goes to the Country. It was time, as we freelancers say, to “dial for dollars.”

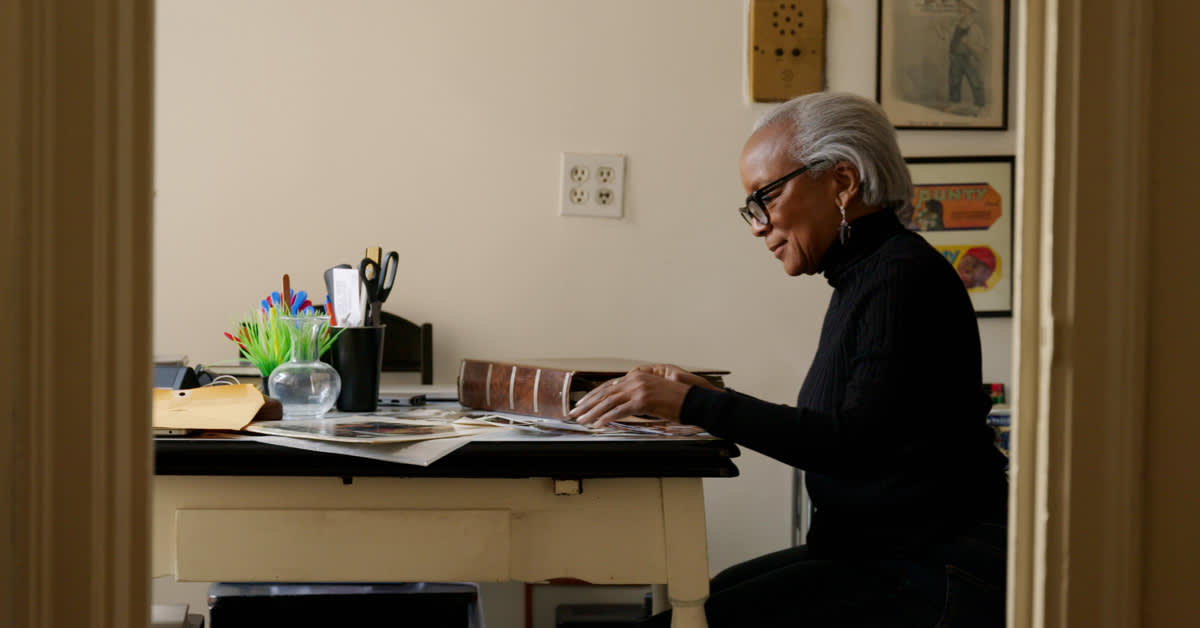

More than a year passed before I resumed work on it, then titled with the punny A Few Good Miles, meant to reference my life and Miles. Since I was in between freelance gigs, I was able to work on it in the mornings starting around 10, a break around 1 p.m., resume at two, and work until four. I don’t like writing at night, I’ll review the day’s work and make note of what I have to do the next day. As long as I could afford to, I worked on the manuscript.

If work came along, I wrote during the weekend, a couple of hours each day.

When I finished that draft (there were five) I cried, a lot. It was a cry of relief, elation, and of course sadness, especially when I re-read the epilogue. Memoir is about truth, and that huge wave of emotion was confirmation that I had told the truth and looked it in the eye.

Finding an agent is no easy task. I have a file filled with rejection letters. I wasn’t a known writer outside of several articles, even though they appeared in national magazines and major newspapers; I still was small potatoes, an unknown. The worst rejections were the ones that implied I had talent, which I knew, but apparently not enough for this agent to take me on.

But one did. She believed in the book and was generous with her time, giving me pointers on how to refine it, to “bring it home,” I say.

Memoir is about truth, and that huge wave of emotion was confirmation that I had told the truth and looked it in the eye.

When I joined Audible four years ago, selling my book was not on my mind. I was excited to be in a new space outside of advertising and in the world of audio storytelling, literature, and performance. My position was copywriter in the Customer Service organization, which is fascinating in terms of what goes on before an agent answers a call. My first task was to rewrite or revisit the articles in the Help Center, a huge task but one that offered a lot of learning. I also wrote a couple of training modules and started a newsletter that profiled the CS specialists who shared their varied and interesting backgrounds.

The first discussions around the book actually started on the platform of the Newark Broad Street train station, where I had befriended several editors on our trips back to the city. It took months to work up the nerve to mention my book. When I did, one said, “Send it to me.” I sent him six chapters, and it was six months before I heard from him. “This is terrific,” he wrote in an email.

In the summer of 2020, that dreadful first summer of the pandemic, my agent received an offer, making me an Audible creator on top of an Audible employee. I realized my colleagues might well become my listeners and, by the time they finished listening, they would know a lot about me—more than I’ll ever know about them. I wondered: Would they walk by me in the halls and give me knowing looks? Would they treat me differently? Through which gaze would they see me and hear my story?

The editing process at times was challenging. Left to me, I thought it was ready to go straight to copyedit: it was my story, told my way. But as always, we are so close to what we write; we can lose objectivity. No matter our disagreement, my editor Rachel Smalter-Hall would say, “It’s your story to tell.”

In the summer of 2020, that dreadful first summer of the pandemic, my agent received an offer, making me an Audible creator on top of an Audible employee.

On top of the edit, there was the copyedit and fact check. I had fact checked along the way, calling friends and family for added details or confirmations. If something couldn’t be confirmed, I didn’t put in the book. For example, I remember Yvette, my sister, telling me that Miles was on a call one day when she was at the house, and after he hung up she heard him say, “[Blank] can’t even sing and makes more money than I do.” He had said the name of a famous singer, which I thought I remembered but when I asked Yvette to confirm, she couldn’t. It might have been a juicy tidbit, but out it went. When the fact check was completed, I was pleased to see “Verified” many times throughout the manuscript.

Finally, it was time to find a narrator. Of course she had to be Black, but one that didn’t think she had to sound Black or be directed to do so. Many times throughout my advertising career when I was working on a product or service directed to the African-American market, the voiceover talent immediately delivered the copy with a certain cadence. I would go into the booth and say, “You don’t have to do that.” One narrator complained that she was often asked by whites in the studio, “Can you sound more Black?” There goes that gaze again.

As soon as I heard Allyson Johnson narrate a couple of pages, I knew we’d found the right person. She understood my sense of humor, and she had a slight rasp in her voice that lent the audio an elegant grit, a texture. She would self-direct and direct me when I recorded the epilogue and acknowledgements late last year. The recording was at the end of the day, and I had plans to go out after. I wore a starched white shirt I thought would be perfect for photographs the engineer was going to take during the session. At a certain point, I was told that the mic was picking up the noise of my shirt, so they gave me a soft blanket. “I can take off the shirt, wouldn’t that be easier?” I asked as I wrapped the blanket around me.

All the while, we were working on the cover art. Fortunately, an art director I’d worked with in the ad business was available. Paul Guayante is one of the most tasteful creators of great beauty campaigns, and he had also designed books. His presentations were always an embarrassment of riches. Since he knew me well, it informed his creative direction. The cover is already getting rave reviews, and fingers crossed, the content will too.