Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

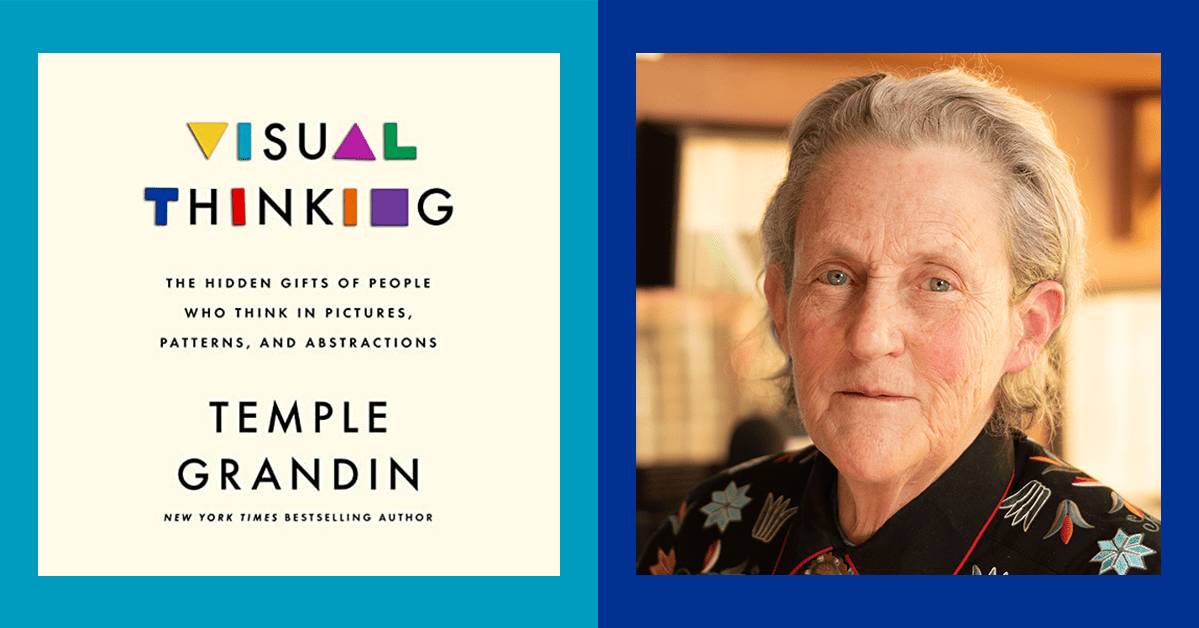

Madeline Anthony: Hi, listeners. I'm Audible Editor Madeline Anthony and I'm thrilled to be speaking with Temple Grandin today about her new listen, Visual Thinking. Temple, welcome. Thank you for being here.

Temple Grandin: It's great to be here.

MA: Listeners, Temple is a scientist, animal behaviorist, and academic perhaps best known for her vast contributions to the meat industry regarding the humane treatment of animals. Temple has also worked to destigmatize autism with her many books, including her memoir, Thinking in Pictures, which was the subject of the award-winning HBO film Temple Grandin.

So, let me just start by saying that this audiobook really gave me a window into the human mind that I had never previously grasped. And it really brings awareness to the fact that people truly think and operate differently, and really the tremendous advantages of that. I found this listen to be extremely optimistic. It's warning about the current way that things are done, but I found it to be more of an optimistic call to action toward a more integrated society. So, Temple, there's so much to get into here, but for listeners who may not be familiar, can you give a quick overview of what differentiates a visual thinker and a verbal thinker?

TG: Well, I think completely in pictures. Everything I think is a photorealistic picture. Like, if I read a science fiction novel, or say I read a historical novel about out West, it's almost like running a movie. When I was young, I thought everybody thought that way. I didn't know my thinking was different. So, my very initial work with cattle, I got down in the shoots to see what cattle were seeing. And there'd be a shadow or a reflection or a coat on a fence, and that would make the cattle stop to go through the shoot to get vaccinated. And I didn't know at the time other people thought verbally and that other people thought totally in words. I didn't know that. Now I've learned there's three kinds of thinking. There's the object visualizer, like me, thinks in pictures. Then there's the more pattern, visual-spatial, thinks in patterns, mathematics, and music, a computer programmer. And then, of course, there's the people that think in words. And in the Visual Thinking book, I present lots of scientific evidence on this too.

MA: Definitely. You said in the audiobook that a driving force behind why you wanted to write it was that you've been witnessing this loss of skills in the country.

TG: Yes.

MA: I'm going to quote you here, that "We're screening out the very people who could save us." Can you elaborate on what types of skills visual thinkers generally excel at and what those skills could translate to in terms of societal contributions?

TG: We're really good with mechanical devices. When you think back to the early inventors, things like grain-harvesting equipment, that was all stuff that was very clever mechanically. So, mechanics, art, understanding animals because they don't think in words, and photography. Those are areas where visual thinkers can really excel. And your more mathematical engineers. Think programming, physics, chemistry, music, those things go together.

Now, the skills that we're losing is what I call the “clever engineering department.” Right now, if you want to build a poultry processing plant, you have to get all the equipment in 100 shipping containers from Holland. That's a problem. We also don't make the state-of-the-art electronic chip-making machines. Because there's two parts of engineering: There’s the mathematical part and then there’s what I call the clever engineering. And when you look at the chip-making machine with the covers off, there's all kinds of clever mechanical stuff on that. That's where we're losing the skills. We also need my kind of mind to keep water systems working, to prevent wires from falling off of electric towers, to keep the infrastructure together.

MA: You actually mentioned climate change. How do you think visual thinkers could come up with solutions?

TG: The verbal thinker overgeneralizes. I'm going to look at it in a much more targeted way. How can we deal with some of the specific problems? Okay, power's number one. And lots of times the verbal thinkers don't think it through. Say, “Okay, let's get all the cars in California electric.” You don't have enough electric power in California to run those cars unless you put an awful lot of solar panels on an awful lot of roofs. And then right now, in certain parts of California, if the wind blows 45 miles an hour, they have to go turn off the power because the wires might fall off the towers because they never replaced the brackets to hold the insulators on. See, I see it.

MA: That's really interesting. I really appreciated how you spoke so candidly about the educational system and the emphasis on standardized testing and the moving away from arts and music programs and the hands-on type of learning. When I was listening to that I was thinking, “Well, how do we completely just change the system?” But working with the current reality of the educational systems today, what advice did you have to parents who see that their child is struggling within the confines of the current system?

TG: Well, I can tell you, if I could do one thing in the schools it’s putting all the hands-on classes back in. Theater, sewing, music, mechanical, fixing cars, welding. I work with people designing and building equipment that took a single welding class. And then they'd be labeled autistic today. But they owned a big shop and they were inventing equipment, patenting it, selling it to industry. I worked with those people. They're all retiring out now. They're not getting replaced. Because the kids that ought to be fixing stuff, like fixing elevators, for example, they're playing video games in the basement, and they're not getting fabulous video-game-industry jobs. I wish they were. But they're not. And then you need the mathematical minds, because that's the mathematical side of engineering. Take food processing, boilers, refrigeration. That's done by mathematicians.

"If I could do one thing in the schools it’s putting all the hands-on classes back in."

MA: You're making me think about the trade industry and how people can sometimes turn their nose up at trade professions. I'm wondering if you think that it's possible to shift that perception away from looking down on trade professions as a society?

TG: We need to not be looking down on them. Visual thinking is a different kind of thinking. I've worked on big, complicated projects. And skilled trades, high-end skilled trades, it's a different type of intelligence, and I think it's hard for verbal thinkers to understand that different type of intelligence that can just see how a mechanical thing works. But I worked with these people and we need these skills. I'm really concerned. Our water systems are coming apart, because we deferred maintenance on stuff. It's a different kind of intelligence. And it's often not given enough credit. I've worked with people that would be labeled autistic today that, you're talking 20 patents, selling stuff around the world, a big shop.

MA: You obviously have succeeded and you've made big impacts in the work that you're doing and the work that you've done throughout your career. Obviously, you went through the education system. What do you think helped you to be able to succeed?

TG: Well, my mother was always pushing me. I had all kinds of hands-on classes in school. That really helped me. I was a horrible high school student. Still can't do algebra to this day. My science teacher gave me interesting projects to do, so that motivated me, an important mentor. And then there was a building contractor that saw some of my drawings and seeked me out to help get his tiny little construction company going, to design cattle handling facilities. People recognize ability. People respect ability. And I learned how to sell work by just showing off drawings and showing off pictures of jobs.

MA: I did see, in preparation for this interview, a talk that you gave, and you had said that being a woman in a man's world, regarding the livestock industry, was a bigger barrier than autism was. That really struck me. And I wanted to touch on that. Do you see improvements in the industry today? And what advice would you give to women who are entering a male-dominated field today?

TG: Well, things are way improved today. I mean, there's lady pilots. I had a lady pilot on my plane just the other day. In the '70s, only women working in a cattle feed yard were the secretaries in the office. And so what I was doing was really radical. Where I had the most problems was middle management. Almost all of my problems was middle management. The owners of a lot of the places liked me. I got along with construction workers and I got along with the guys just working out there with the cattle. Middle management, I think they felt threatened.

The other thing I had to do is make myself extremely good at what I did. And then I wrote about my projects. I wrote a lot of how-to articles. Just how to handle cattle, how to design stuff. Yesterday, I was at a sustainable food conference and one of the things they talked about was berry boxes, like the strawberries, blueberries, plastic clamshell things. What to replace those with. Well, okay, that's something targeted. That's something doable. Improving cattle handling is doable. It's not the whole world.

MA: So, in terms of getting yourself to be taken seriously in this male-dominated industry, it was more about just showcasing your skills again and again?

TG: Yup. And I read about things, and making myself extremely good at what I was good at doing. And when somebody got in a real mess, I was the one who could fix their stuff.

MA: You are widely regarded as an advocate for people on the autism spectrum. But it's not one of the main ways you identify yourself. And you talk in the audiobook a lot about getting out of the disability mindset. And I'm curious to hear you elaborate a little bit more about that.

TG: There's a lot of talk about identity. I've done a lot of thinking about this. I think I'm career first on identity. I am a university professor, a designer of livestock facilities. And autism's a very important part of who I am, but I don't let it totally define me. See, autism goes from Elon Musk and Einstein and Tesla to somebody who can't dress themselves, and you've got the same label on it. That's an example of verbal thinkers overgeneralizing. And people kind of get locked into the labels. Now, there are things that are different. I had to learn to be social. I don't do the party scene. I have friends who share interests. I had a fantastic flight, we spent two hours talking about such interesting subjects. Tilt-up warehouse construction and concrete forms. That was just so interesting.

"Autism's a very important part of who I am, but I don't let it totally define me."

MA: So, for you, it's about making sure that interests are the same. That makes sense. I want to understand your thinking behind getting out of this mindset. Do you think that that holds people back?

TG: Well, if you get in that mindset, it does hold you back. I think there's some stuff you have to do to conform. I dress eccentric. But you can't be a rude, filthy, dirty slob, you know. I got counseled on the very first job I was on. I first criticized some welding and I said, well, “pigeon doo-doo.” And, fortunately, the plant engineer was a good job coach. He pulled me into his little office in the boiler room. He says, "You're going to have to apologize for that kind of language. That's not acceptable."

I had to learn I couldn't call people stupid. You see, I didn't know about the different kinds of thinking. People would make visualization mistakes—I remember one system, they pulled a whole bunch of rails out of the ceiling, and I could see, by the mistakes they made, that they would tear those rails down. I saw it. It wasn't stupidity, it was lack of visual thinking. This is where you need the different minds working together. When we worked on the Visual Thinking book, I would write the rough drafts, and Betsy [Lerner] smoothed it all out and made it flow. That's complementary minds working together. Knowing each other's skills, and complementary skills. Really important. We need that.

MA: How important do you think it is for people to be aware of what kind of thinker they are?

TG: I want to emphasize a lot of people are more middle-of-the-road mixtures. But oftentimes, the kids that have the labels, they'll be an extreme mathematician or an extreme object visualizer. I visited a beautiful dairy up in Quebec. And they use these robotic milkers. And the dairymen modified the design of the thing. The company threw a fit. Then he voided the warranty, and then he turned around and copied his modification. He says, “I work on the mechanical stuff. I stop at the software.” See, that's where I'm going to need the more mathematical mind to do the programming. I took a programming class in college, I had to drop it.

MA: On the topic of education, you outline that a good percentage of college grads earn no more than the average high school graduate. And that a significant percentage of college grads actually hold jobs that don't require a degree. The audiobook reminds us that academic achievement in high school and college is not necessarily a predictor of achievement later in life. So, if you were to look ahead, maybe 10 or 20 years, do you think that going to college will still be the expected norm?

TG: Well, there's a lot of jobs you need college. The one exception is the high-end skilled trades. I know people that have corporate jets, big companies, but it's all mechanical stuff. And when you go to visit this guy, he doesn't have coffee with you first. “Oh, we're going out in the shop. I gotta show you my new machine tools.” It's all about the shop.

MA: Something else that really struck me that I wanted to ask you was that you talked about the fact that from a brain scan, you learned that your emotion center is three times bigger than the average.

TG: My fear center. My fear center was three times bigger.

MA: Okay.

TG: And also a huge visual thinking trunk line was discovered in my brain.

MA: Oh, interesting. It struck me, because I was thinking I have anxiety and I've always thought of anxiety as a response to external forces rather than something different in the physical brain.

TG: It can be both. You see, the physical brain is the more primitive stuff. Now, my fear center's overactive. Totally overactive. I have been on antidepressant medication for 40 years. I take a very low dose. It's explained in detail in my book, Thinking in Pictures. It's still accurate even though it's old. It saved me. As I went into my 20s, I had done those dip vac projects that were in the movies. My health was falling apart with colitis attacks. That's why I was eating yogurt and Jell-O. And then I went on a low dose of an antidepressant medication. I've been on it ever since.

Now, let's say my emotion center had been double the size rather than triple the size, then maybe top-down control from up here could suppress it. I've talked to students that have problems, and I explain to them, I say, “Drugs hit the bottom of the brain; therapy and talk hits the top of the brain.”

MA: There's multiple things going on.

TG: Milder anxiety, you can probably control it top down, with therapy. Where you start looking at the glass as half full rather than half empty. And during COVID, one of the things that helped me was I said, “We're lucky. We're going to be getting a good vaccine. We have hospitals here. I have a house to live in.” I started purposely making myself look at the glass as half full rather than half empty.

MA: Did you take some time off of work during COVID, or were you able to still go out?

TG: No, everything was shut down, pretty much. Classes all went online. I'll never forget the horrible meeting they had, they pulled all us in and said school is closing and you have 10 days to get your classes online. It was bad. So, I spent a lot of time doing that, and I did have a few projects I worked on extremely carefully. But all my speaking engagements, all live engagements, were canceled.

MA: I'm curious, talking about COVID and going remote, and talking about education. It's got me wondering, do you think online learning is more difficult for visual thinkers?

TG: Not necessarily, no. I think online learning is the younger the children are the worse it is. Because you're not getting the social interaction.

MA: In the book, you draw connections between animals and humans, and show how animals are visual thinkers. Super interesting.

TG: A better thing to say is they're sensory-based thinkers. Because dogs, smell is their main world. In fact, I just read a really super interesting piece of research from Cornell University that the dog has a gigantic trunk line going from the nose to the visual cortex of the brain. I'm going “Trippy. Smelling in pictures.” And that's brand-new stuff. It's not in the book because I just learned about that. But the animal lives in a sensory-based world. Not a word-based world. There's a really good book I recommend to veterinarians, besides my Animals in Translation. It’s An Immense World. That's about animal sensory systems.

MA: Wow.

TG: An octopus lives in a touch world. There is a chapter on there on animal consciousness and I think the problem with this is the people that are completely verbal, who think only in words, I think they have a hard time imagining a dog's conscious and can even think. Since I think in pictures, I think it's obvious the dog is conscious and he's able to think. The main difference is, we've got a computer sitting up here that's a whole lot bigger.

MA: You are drawing these commonalities between humans and animals. I'm curious, you've obviously made tremendous strides forward in terms of the humane treatment of animals. Do you believe that the meat industry is becoming more humane? Is it headed in a more humane direction?

TG: There’ve been some big improvements in animal handling. I've worked on that. And improving animal handling, slaughter plants, animal handling on ranches, that's gotten a whole lot better. Because in the '70s and '80s, it was terrible. Now there's other people working on animal handling, so that has improved. But the thing that we've got to do is we've got to give animals a life worth living. We've got to give them a good life.

In fact, I think a lot of dogs have a rotten life. They're too locked up now and they don't get out and explore enough stuff. I was just up at this lovely dairy in Quebec, and I got to stay with them. And they had rescued a dog. It loved being on the farm, out doing things. A sheltered life, it's not a very good life. And I think a lot of kids, especially if they have a label, I'm seeing parents overprotect them to the point where fully verbal smart kids are not learning shopping, bank account, laundry, ordering food in restaurants, just basic, basic stuff they're not learning.

MA: Maybe some listeners will have a child that's on the spectrum. And I'm wondering, you're saying they're not learning these basic skills. What are maybe some simple steps that a parent could take to kind of stretch their child out of that?

TG: Give them some choices of things to do. There's been a lot of problems with them just playing video games and doing nothing else. You gotta replace it with something else. And there's been some real successes. We're replacing with car mechanics, and the visual thinkers find that more interesting. The other thing I emphasize to business people, you need these skills. Right now, we can't find people to fix elevators and fix factories. There's a real issue right now on that. And I can think back on when I was out on construction sites. For about 25 years, I was living out on construction sites. And I'm going to estimate that about 20 percent of the people that were laying out and designing whole factories, inventing mechanical equipment, and welding, were either autistic, dyslexic, or ADHD.

MA: What do you think is the next step that the meat industry could take in terms of reducing unnecessary animal suffering? Do you see next steps there?

TG: The animal that probably has some of the best welfare is beef cattle.

MA: Really?

TG: The cows and the bulls are out on pasture. In fact, I've been getting really interested in how pasture done properly can improve land. You can actually improve land, sequester carbon, improve soil health, pasturing cattle, sheep, and other animals on cover crops every third year. Crop rotation, grazing sheep under solar panels. Solar panels need something constructive going on under them. And we could actually use grazing animals to improve land. We have to do it right. They can wreck land. They can totally wreck it. And so some of the best welfare is beef cattle, when they're done right. Gotta emphasize that. We have huge amounts of land here in Colorado that you cannot crop, it can only be grazed. There's not enough ground water for crops, for sprinklers, and there's not enough rain for dry land farming. The only thing you can do on that land, and it's 20 percent of the Earth's surface, is grazing. I’m talking about land that's way too arid to have something on it like a rainforest.

MA: I'm curious about switching gears to your reading habits. As a visual thinker, do you prefer reading, or listening to audio?

TG: I would prefer reading. And I'm really happy that a lot of people are listening to my books in audio. On one of my books, a third of the royalty checks were for audio. I prefer reading. I like marking up books for things. And I'll remember things I can visualize.

MA: You narrated the introduction as well as the afterword yourself. I'm curious, did you feel like that was something you felt strongly about, and how did you find the process of narrating your own work?

TG: Well, I think it was the right thing to do. I'm remembering, we did a really funky thing in the studio over on campus. We had to make a stand. Well, they had a drum set in that studio, so they made a stand out of a drum set and a sign about headphones, and leaned the papers up against that so I didn't have to touch them. It was very clever.

MA: That's awesome. So, you recorded at Colorado State?

TG: Yeah, I recorded at Colorado State.

MA: Well, I thought it really helped to get across how passionate you are about the subject in your own voice.

TG: Well, I'm very concerned about these jobs not getting replaced. Some of these skills that people tend to kind of think is a lesser form of intelligence, we need these skills. And I want to make it very clear that it's only for a section of the autistic population that would go the skilled trades route. The other routes are going to be to Silicon Valley, computers, chemistry. We need these skills. I don't think educators get it. They don't do anything with industrial stuff, or livestock stuff.

MA: You've had a very long and impactful career. What kind of impact are you hoping to have with this audiobook, and what do you hope people will take away from it after they're done listening?

"I hope [Visual Thinking] is going to help the kids that are different get out and get great careers and do really constructive things."

TG: I hope it's going to help the kids that are different get out and get great careers and do really constructive things. I'm now in my 70s and what I want to do is encourage the next generation. I just talked to a class of animal science, freshman students, this morning about cattle handling. But I also said to them, “You're the leaders of the future. We have got to find solutions to problems, not just talk about stuff in a vague, abstract way.” How do we actually solve problems? And back when I first worked on cattle handling, well, that's something relatively targeted. Design the facilities, and then how you use those facilities. And too often people want the magic thing, the computer, the drug, whatever. Magic equipment more than they want the management. I've been learning more and more the importance of the management, attention to detail, to do things right.

MA: Well, thank you so much for sharing your time and your knowledge. And listeners, you can listen to Visual Thinking on Audible.com now.

TG: Thank you so much.