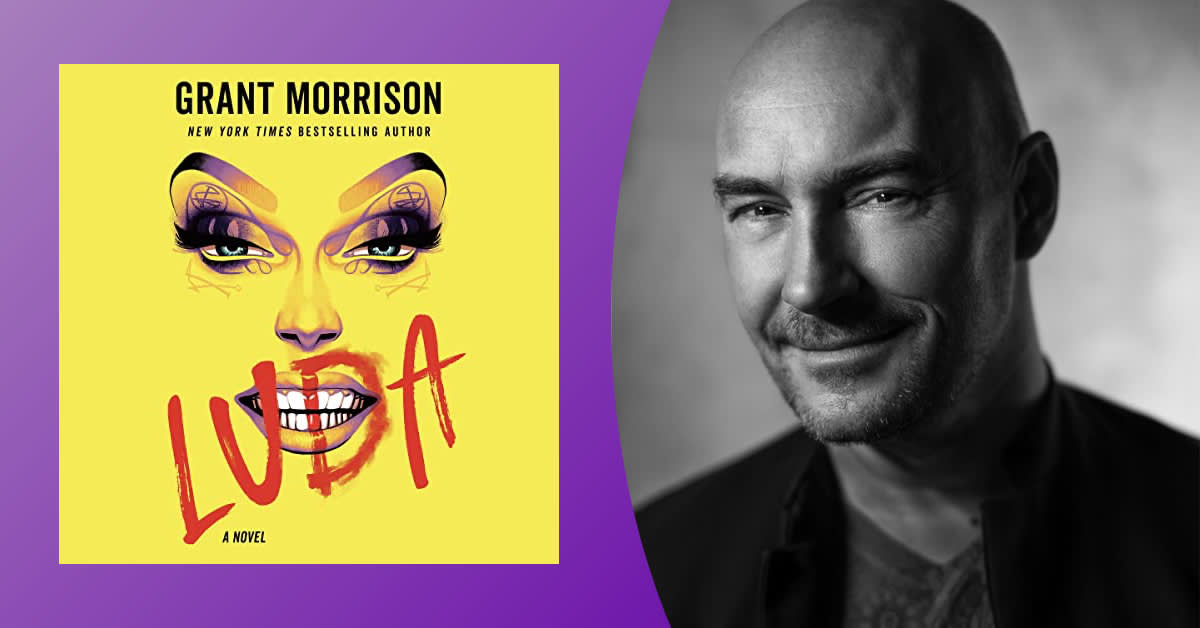

No doubt one of the most famous comic book authors to put ink to page, Grant Morrison truly needs no introduction. Their graphic novels, including the brilliant Arkham Asylum, and work on longstanding series including Doom Patrol, All-Star Superman, and Animal Man have been hailed for a subversive, high-concept narrative structure that broke the mold and set new standards for innovation in the medium.

It’s no surprise, then, that Morrison’s first novel delights in the entrancing charms of the unreliable narrator, the nature of identity, transformation, perception, and the swirling, obscure world of the occult. Morrison shared with us their thoughts on crafting a “psychedelic effect” throughout Luda, the fascinations of a self-mythologizing protagonist, and the songs that scored their creative process.

Many fans may be familiar with you and your work through your acclaimed, inventive work in the comic book medium. What was it like translating that skill set to writing your first novel, and what compelled you to take that format leap?

My agent has been urging me to write a novel for almost 20 years! A combination of stepping back from the grind of monthly serialized comic book fiction and the enforced isolation of COVID provided the ideal opportunity to see it through.

Otherwise, I’ll take any opportunity to write for different media—learning the tricks and tactics, the possibilities and limitations of various narrative delivery systems keeps the work fresh and unpredictable for me. When I’ve written for comics, TV, or the stage, it’s very much a collaborative effort, with artists, colorists, letterers, actors, producers, et cetera. Writing a novel, on the other hand, is a solo flight: It was my job to bring the imagery and color I usually rely on artists to provide, using the wonder of written words alone.

I wanted Luci’s narrative to create a psychedelic effect of vivid simulated experiences, color, sound, and energy suggesting an intoxicated, peacock perception that transforms very ordinary, often squalid circumstances into legend. I seized the opportunity to hurl chunks of dictionary at the blank page in the manner of Pollock chucking tins of paint at an unsuspecting canvas!

That kind of flamboyant, or carnivalesque, use of language is common to comics, and—in the way each chapter of Luda somewhat tells its own complete story in its own style—the episodic nature of monthly comics and weekly TV can be seen as an influence.

Your debut centers on aging drag queen Luci LaBang and her protégée, the titular Luda, rooting this hypnotic, labyrinthine work of magical realism in the world of queer art and performance. Were you at all inspired or influenced by your own experiences navigating gender, identity, and self-expression in building the book’s setting and characters?

Very much so. While I hasten to point out that Luda is very much a self-consciously artificial work of fiction, the only way to make the central conceit work was to build the book around real feelings, real regrets, real dreams and fears, and convincing ways of seeing or presenting to the world.

Luci LaBang’s biography is her own, but I gave the character permission to use any and all embarrassing, amusing, or heartbreaking details of my personal experience that she deemed necessary to help weave her Glamour!

The language used throughout Luda is vivid, vibrant, referential, and has a pull all its own, perhaps mirroring the hypnotic magic of Glamour itself. What’s your creative process in crafting description and dialogue that conveys not only meaning but a sense of atmosphere and power?

An early version of Luda was created to be an Audible novella, which led to the central idea of the single unreliable narrator telling us a story—seemingly involving crime and magic—entirely from their point of view.

Given the Talking Heads monologue nature of this approach, it made sense for the writing to be charged and evocative, showy and performative, both in keeping with its subject and as a way of making the listener’s experience more immersive, more musical, and hypnotic.

Any plain or direct prose was then subjected to a process of Cinderella-like transformation into its own florid, pop lyric alter ego before being thrust onto the spotlight stage of the page, blinking nervously in heels and false eyelashes.

Signature in its boundless imagination, your work is known for its grounding of the unconventional and unexpected in distinctly human themes. Luda, certainly, is no exception. What would you say is at the heart of good storytelling? Is it a matter of invention, emotion, or a combination of the two?

Richer stories tend to have generous servings of both. And a bit of everything else. I can bore to Olympic medal standard about the engrossing structural intricacies of Luda and its multiple reflecting, feedbacking metaphors, or the games it plays with Arthurian legend and the Golden Section—but the behind-the-scenes technical stuff that excites me only works in service to the containing and shaping of feelings that are raw and recognizably human, and the creation of a character who is driven by the kind of contradictory, often self-deceiving impulses that readers can identify from their own real lives and relationships. The untying of complicated emotional knots releases powerful energy, but the story, the structure, the scaffold of artifice is what shapes the unleashed cri de coeur into a compelling thriller or elaborate enthralling magic trick.

In terms of invention, in the sense of concept generation and compared to most of the comic books I’ve done, with Luda, I tried to dial back on anything overtly fantastical or suggestive of genre. The magic is practical, the counterintelligence mind control techniques are real, the phantasmagorical, shamanic elements of the Glamour are matters of perception and performance.

What gives the book its weird and witchy flavor is Luci LaBang’s singular way of looking at the world and how she mythologizes her role within it. She sprinkles stardust and sequins, wit and invention wherever she goes, but the Glamour’s fascinating smoke and mirrors serve also to obscure agonizing decisions, thwarted romances, broken promises, mental health crises, and worse…

Though you’re known best for your Eisner-winning comics, you’re also a musician and a big music fan. Are there any songs or artists in particular that scored your writing process for the novel?

Luci LaBang listens to Thomas Tallis’s 16th century choral masterwork “Spem in Alium” as she’s prepping her makeup to go onstage, so definitely that. She usually follows up with the Sex Pistols’ “Pretty Vacant,” which is another blatant shoutout to the story’s themes, as is her ringtone, “Two Ladies" from Cabaret.

“Widow Twanky” by Momus contributed its wry and bittersweet swing to the rhythm of Luda. As I was wrapping up the final edit, I discovered Tessie O’Shea doing Arthur Le Clerq’s cheeky 1934 tune “Nobody Loves a Fairy When She’s 40,” which plays like the perfect ironic end credits theme for Luda!