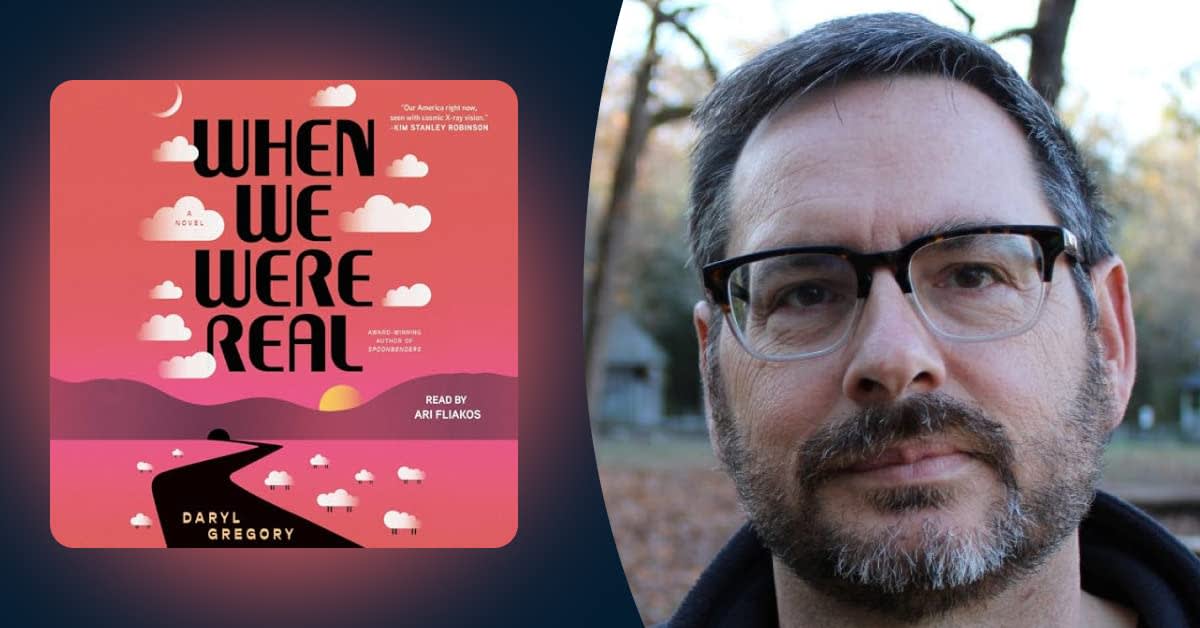

Daryl Gregory (Spoonbenders) is known for his genre-bending stories, ripe with absurdism and irreverent humor, yet full of heart. His latest, When We Were Real, may just be his most ambitious yet. The novel follows a bus full of tourists on a weeklong journey to see the Impossibles—glitches and anomalies in the digital simulation they live in—who find themselves confronting some very real emotions along the way. We caught up with him about his inspiration and our own simulation's—ahem—world’s most Impossible feature.

Sam Danis: What was the inspiration behind this story? Were there any real-world influences for the passengers of this tour?

Daryl Gregory: Those records are sealed.

I kid! Though my sisters did once buy me a sweatshirt that said, "Be careful or I'll put you in my novel." That's because like most writers, I steal from my loved ones, then try to cover up the crime. I change physical details, swap genders, and put their words in other characters’ mouths so friends and family can't identify themselves.

But I will come clean on one thing for this book. The most direct inspiration came from my friend and fellow writer, Jack Skillingstead. Jack and I took a cross-country road trip from Chicago to California at a time when I really needed him. Then a few years later, Jack had surgery for a brain tumor (he's fine now), and those two events were the germ of When We Were Real. In the book, two old friends, JP and Dulin, go on one last trip across America, after JP's cancer has returned. As the writing progressed, JP and Dulin diverged greatly from Jack and Daryl (Dulin, for example, is 6'2 and I'm ... not), but our relationship and theirs became the heart of the story.

The story has such an interesting, dramatic, omniscient point of view. What led you to choose this voice?

In the book there's an unidentified, mostly omniscient narrator that's actually a group speaking as "we." They introduce the passengers on the bus, and then dip in and out of the story. They're not objective—they have definite opinions on how things are going.

The process of deciding on those narrators was fairly organic. First, I knew that I wanted lots of differing opinions on how to live in a simulation, so that meant JP and Dulin should have fellow passengers on the bus. At some point I realized that the book was sounding a bit like Canterbury Tales, but with 21st-century pilgrims, each of whom should get a chance to tell their story. And that led me to writing an opening like Chaucer's prologue. In Tales, the narrator is Chaucer himself. But who should it be in this book?

That led me to thinking that perhaps they're watching the simulation and commenting on it, like fans watching their favorite show. And if that's true, then obviously the book has to be written in present tense! And then, of course, I had to decide who, exactly, these narrators are, and why they're taking such an interest in these particular people. The final revelation of their identity and aims turned out to be an important part of the story.

I think that's an example of something that often happens to writers—or to me, anyway. One choice starts a cascade of other choices, because the story demands them. As the writer Michael Swanwick says, the book is the boss.

Ari Fliakos previously narrated your novel Spoonbenders. What was important to you when it came to narration for this story?

I just loved Ari's work on Spoonbenders—and so did many readers who wrote to me. That book also had a big cast (though not as crazily large as the one for WWWR), and he's so good at making every character distinct. He does voices but never goes over the top. And he's so good at humor! Both Spoonbenders and this book depend a lot on comedy and banter. So when they asked me who should narrate this new book, I knew exactly who I wanted.

And speaking of all those characters, here's something for you audiobook listeners—you can download the bus seating chart from the homepage on my website. If you have the physical book, it's there on the opening pages.

If our world were a simulation (and it hasn’t been proven that it’s not!), what would you consider the world’s most Impossible site or experience?

The one I think about all the time is UFOs—or UAPs as they're now called, meaning Unidentified Anomalous Phenomenon. A few years ago, the government released hours of video, voice, and sensor data of military pilots witnessing weird things in the sky (and sometimes diving into the water). If we can believe the sensors, these objects break the laws of physics, just like Impossibles do. Yet when the tapes were released, and Congress held hearings on them, the world shrugged. That is hilarious, and also the most human response possible.

I'm not saying that UFOs are aliens, or from the future. We just don't have the evidence (and as Carl Sagan says, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence). But I wouldn't be surprised if when the simulators reveal to us that we're actually all digital beings, they point to the flying saucers and say, “We tried to tell you!”