I’ve been DMT-curious ever since my octogenarian father made psychedelics his pandemic hobby, culminating with a life-changing trip on the stuff, courtesy of the psychoactive secretions of the Sonoran Desert toad.

Whether harvested from a frog or brewed in ayahuasca, the so-called “God molecule” is common yet strangely complex to activate. It’s really more of a drug technology, according to the scientist Andrew R. Gallimore, author of , a mind-bending, science-stuffed history of DMT. Even odder? DMT trips often involve elaborately detailed visions of busy insectoid aliens, xapiri (spirits that inhabit the Amazon rainforest), and elves, which Gallimore distinguishes from mere hallucinations and even psychic archetypes. What he speculates they are is the real trip.

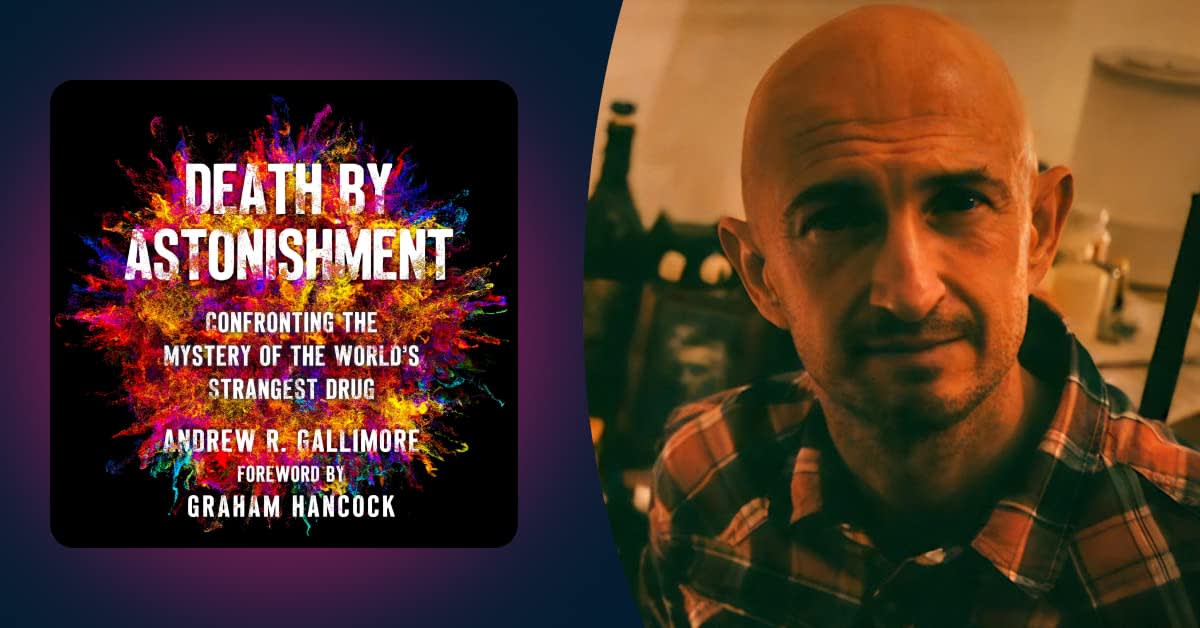

Populated by counterculture icons such as Terence McKenna, who inspired the title, and with a foreword by Graham Hancock, Death by Astonishment will thrill psychonauts and anyone interested in the mysteries of consciousness. It further ignited my curiosity about this strangest of psychedelics, so I was thrilled to talk to Gallimore about the ideas, experiences, and ramifications behind the book.

Kat Johnson: Congratulations on the new book, it's fascinating, and I'm currently having my mind blown by it as I write this! Can you share what drew you to focus on psychedelics in your career, and then DMT more specifically?

Andrew R. Gallimore: When I was very young—seven or eight—my thing was ghosts, werewolves, vampires, and the paranormal. So, I guess it wasn’t such a surprise that, as I entered high school, my interests started to shift toward unusual states of consciousness—and psychedelics are certainly the most efficient way to achieve these. But DMT, in particular, doesn’t merely generate an unusual state of consciousness but arguably the strangest state of consciousness a human can experience. After my own experience with DMT, I knew that I wanted to spend my life trying to understand and make sense of it.

You seem fun at parties, and I mean that totally sincerely. How do you describe your work and this book to casual acquaintances, and what kinds of reactions do you tend to get?

How I describe my work depends somewhat on whom I’m speaking to. I rarely get straight to the alien intelligence thing. Instead, I’ll start by explaining that I study the neuroscience of psychedelics. If I get a positive response—which is most of the time—I’ll progress to DMT and, eventually, to the idea of using the molecule as a technology for communication with advanced discarnate intelligences. Most people are surprisingly open to these ideas once I explain them, and they realize I’m not totally crazy.

I always describe my work as about 80 percent deconstructing and analyzing—using neuroscience—more orthodox explanations for the effects of DMT and showing why they fail to explain them. It’s in that remaining 20 percent that I work to develop the alternative explanations, including the idea that DMT allows us to interface with some kind of intelligent agent—this is the approach I use in . I certainly didn’t leap to this conclusion but, in fact, feel that I was forced to reach it. We can now explain how, in the presence of psychedelics, the old familiar world begins to break down, becomes more fluid and unstable, less predictable and more novel. We can even explain how and why certain types of imagery—drawn from personal memory or influenced by inherited archetypal patterns, as well as from spontaneous emergent patterns of brain activity—tend to present themselves to a tripper.

Unlocking the secrets of the world’s weirdest psychedelic drug

With “Death by Astonishment,” scientist and psychonaut Andrew R. Gallimore delivers a mind-bending history of DMT.