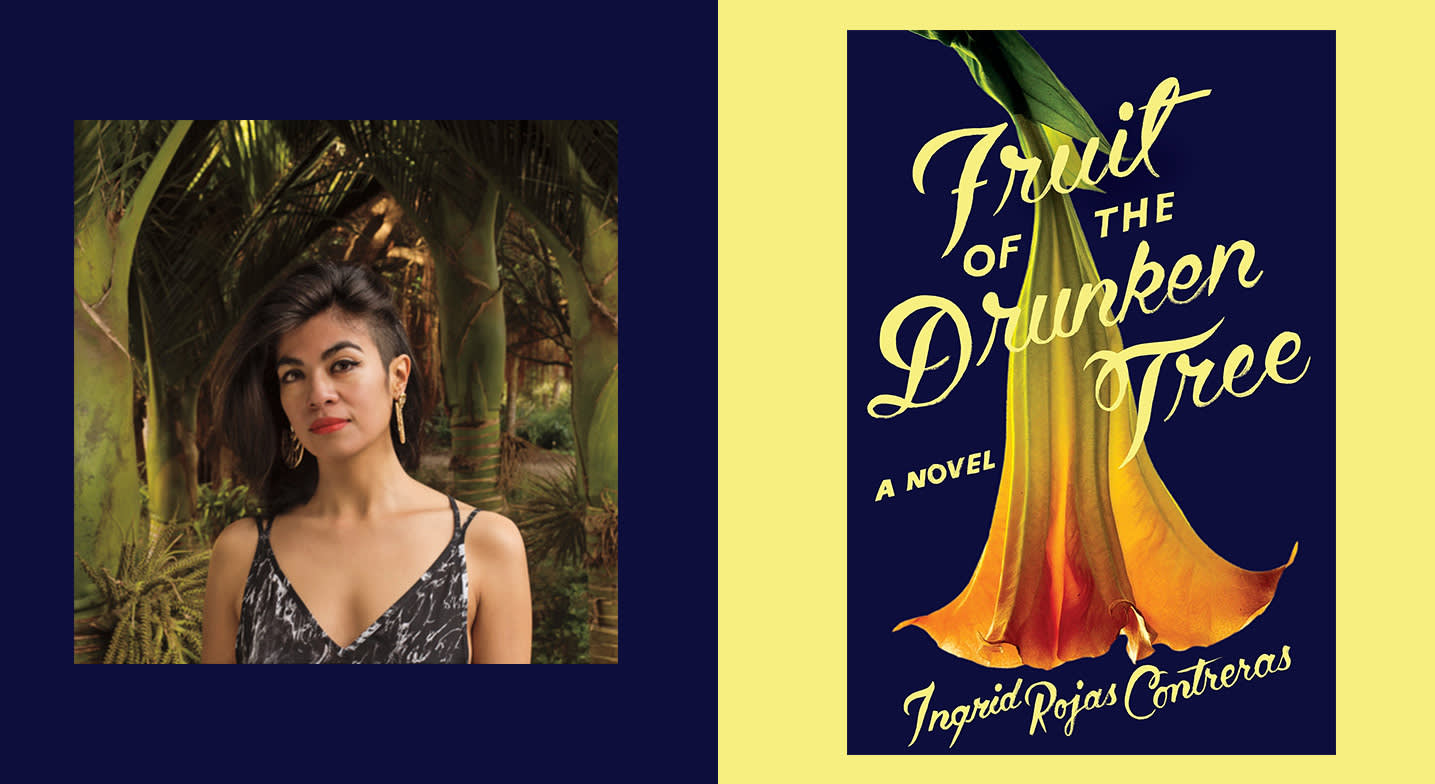

Pablo Escobar seems to be in vogue these days, due in large part to the hit series Narcos from Netflix, but for those who lived through his "reign," the reality of the ruthless killer and drug lord was vastly different (and far less glamorous) than a made-for-television portrayal, particularly when viewed through the eyes of a child. Enter Ingrid Rojas Contreras and her debut novel, Fruit of the Drunken Tree, which tells the story of an unlikely friendship between two girls as the bloodshed wrought by the Medellin Cartel in 1990s Colombia remains ever present in the background.

Audible Editor Kyle sat down with the award-winning Contreras to discuss not only what it means to grow up in a war-torn country and then revisit that past, but also what it means to a family when they decide to uproot their lives and plant themselves in another country in search of safety and peace.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Kyle Souza: Let's talk about your brilliant debut, Fruit of the Drunken Tree. We recently did a feature on how books written from the perspective of a child can illuminate very serious topics sometimes far better than when they're approached from the perspective of an adult, and I'm curious: Why did you make the decision to tell the story from a child's perspective, and what do you think you gained from having these youthful points of view?

Ingrid Rojas Contreras: I was thinking about how when you're a child, you understand things in part, and when there is violence surrounding that child, it becomes even more intense. The situation intensifies. Even when you're a child, you pick things up and you get the gist of it. You know that there is violence happening, and you know that perhaps there is danger surrounding you. It's a little bit of a tragic situation because often children can't figure out things quickly enough.

As I was thinking about Colombia in the '90s and the '80s, and how politically the president had less power than [drug lord] Pablo Escobar and there were all these things that seemed to be out of the control of the people who are supposed to be controlling and keeping the country safe. It felt like we could think of all Colombian citizens as children revisiting that time when you're not in control of anything, and the situation is hard to understand. So I thought that to choose a child who's going through two different types of violence, it would create a kind of mirror to what it was like to live in Colombia regardless if you were a child or an adult.

I also was very interested in their innocence and in the way that children can misinterpret the political information that they do get. We are getting the whole picture and so it becomes even more tragic to read from the standpoint of a child who is trying to piece it together, but can't do it fast enough.

KS: Were there any challenges to writing from a child's point of view?

IRC: Yeah, that was difficult, but I think the thing about a child's perspective is that when you're a child you can come to love anything simply because it's part of your childhood, so it carries that nostalgia and so that even if there is violence happening, or even if there are terrible things happening, you still think of it as the place of your childhood, so it carries all those warm feelings. It's a very complicated emotion, when there's violence around us. In some ways I was so focused in trying to harness that emotion that all of the other things were secondary to that. So even if I could get in a political detail, it was less important to me.

With Pablo Escobar, you can start to think of Colombia as a character that is visited with all these different tragedies and all these different obstacles.

KS: I know that the book is loosely based on your life growing up in Colombia. How much of that is actually reflected here? Is this more of an autobiographical novel, or is it just pieces that you took from your childhood that you wove into the story?

IRC: I began to write the book when I was in Chicago and I was changing visas. I couldn't travel at the time because my paperwork was in transit; I didn't have the permit required to leave or enter back into the country. It was Christmastime, and I didn't have family in Chicago and everyone had left. It was snowing, I was alone, I had this desire to go back home to Colombia, and because I couldn't, I just started to write it for myself.

I wanted to return there, and so the very first things I wrote started from a real place. In fact all the characters in the book have a real counterpart. The more words that I put down, the space between me and Chula, who's my counterpart, widened so that eventually there would be times where I wouldn't know what she was thinking or wouldn't know what she was about to do. But the situation of Chula befriending Petrona, who lives in guerrilla occupied territory, and Petrona being threatened to act against the family: All that is true. All that did happen.

KS: And to continue that, I assume you had to do a fair bit of research into the timeframe and everything that was going on, just to fill in some of those gaps in your memory. Was there anything you were surprised by? Is there anything that when you were sitting down you said, "Oh wow, that's much different than I recall?"

IRC: At the time that I was doing research it was amazing: Google was scanning newspapers, and you could actually search entire Colombian newspapers, and you could see the whole thing. So, my research was very easy at the time.

I would come across all of these very interesting plot lines that were happening with the drought, and with Pablo Escobar, you can start to think of Colombia as a character that is visited with all these different tragedies and all these different obstacles.

There were so many things that I wanted to put into the novel, but there just wasn't any room or any need for it. Like when the drought got really bad in Colombia and people were living without electricity for long periods of time, the United States actually sent a boat filled with generators to Colombia, and in the news it was just the saga of where was the boat and how close the boat was to getting to Colombia. And it got to the shores and then for some reason they couldn't disembark the equipment, so it was just this boat that came with all the electricity that we wanted, but we couldn't actually receive it.

KS: Oh wow.

IRC: But I lived through all the time that the country was searching for Pablo Escobar, and I do remember it was the story that all Colombians were invested in. And I didn't follow as closely the discovery of all the hideouts, and when I read about those, that really surprised me. It was like a James Bond movie where if you opened the faucet of a shower that the shower wall would pop open and there would be a room behind it. So that really surprised me, and that was really fun to write too.

KS: I feel like Pablo Escobar documentaries are very popular programming in the last three or four years. Do you have an appetite for any of that?

IRC: I do enjoy watching it, and I have read a lot of Pablo Escobar books, but I do think that there is a glorification of him that happens. He was just such a mastermind of public opinion, and I'm a little bit turned off by that part of it. But he was both things. He was very charismatic, but he was also a very ruthless and monstrous individual. In the end, I think I would like to see both things presented instead of just the glorification.

This is a novel that looks at how you make amends when you each go through something tragic and you meet together again. How do you start again? How do you become a family again?

KS: I'm sure you've been watching the news these days and you're seeing the issues around Immigration and Customs Enforcement policies, and how they're treating families. Is there anything that people can take from Fruit of the Drunken Tree and apply to their understanding of what immigrants and asylum seekers are going through?

IRC: As an immigrant, I've thought about immigration a lot. Chula's family, they come in as refugees to the US, and it was during a time when it was easier to come because it was before 9/11. After 9/11, there was this law passed that if you had given any kind of material support to an arms group - whether it's paramilitary or guerrillas - you couldn't apply for refugee status. What that could mean is if you owned a farm in Colombia and the paramilitary came and they held you at gunpoint and asked to be fed, if you fed them that could be material support and could exclude you from even applying to be a refugee. Even if you unintentionally got in a very dangerous situation.

The laws have always been a little bit at odds with the reality of people's experience, and that has been going on for a long time. [In the book] there is a separation from one of the characters who can't migrate with them, and I think that's something that is a parallel to what's happening right now with people being separated at the border. Even though it doesn't happen in the same way, it is a lot to bear, to be separated from a loved one. Then when you're reunited, because of the intensity of what you each went through separately, you have to get to know each other again. You can't just pick up where you were before. You're both changed by your situation.

This is a novel that looks at how you make amends when you each go through something tragic and you meet together again. How do you start again? How do you become a family again?

KS: What would be your words on why Fruit of the Drunken Tree is a must-listen?

IRC: Well, it's an immigration story and I think when we hear about violence from a child's point of view we get to the purest experience of violence, because it can't be logically explained in the child's voice. It can only be emotionally understood, and so I think as readers we can get a more real approximation of what it's like to live through violence or to live through threatening times. I think in this novel I also wanted to complicate our understanding of what the civil conflict has been in Colombia.

Often when we hear about it in the United States we just get a body count or that there was a guerrilla confrontation with the army, or they found a mass grave and there was this many bodies. One of the stories that I often heard while I was in Colombia or when I go back to visit are all these stories of women who were forced to do something for the paramilitary or the guerrilla group. I think if we got that story [through the media] that woman would just be [seen as] a guerrilla member, and the nature of how she became part of it would be completely lost. And this is a book that tells that story.