Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly

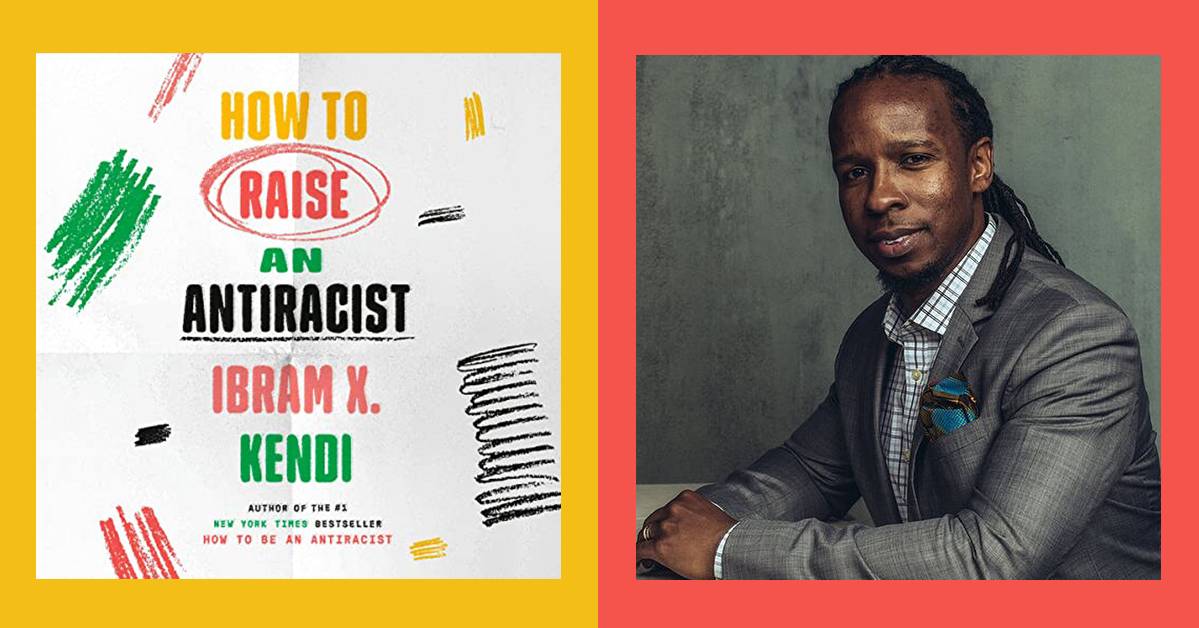

Katie O'Connor: Hi, listeners. I'm Audible Editor Katie O'Connor and I'm honored to be speaking with National Book Award–winning author and director of Boston University's Center for Antiracist Research, Dr. Ibram X. Kendi. Welcome, Dr. Kendi.

Ibram X. Kendi: Oh, it's great. Thank you so much.

KO: And congratulations and happy publication day. We're recording on June 14, and today you have not one, but two books out: a children's book, Goodnight Racism, and How to Raise an Antiracist, a book that is part memoir and part guide for caregivers on their journey to raise the next generation of antiracist thinkers.

I love how you emphasize in How to Raise an Antiracist that it's okay if you're coming to this book and your kid is a teenager. You can start whether your kiddo is in diapers or if they're on TikTok too much. It's just never too late to start enacting these principles. Can you expand on this for our listeners?

IK: Well, I think that there are many different caregivers and their children are at different stages of their development. So, I first did not want teachers or parents or educators or caregivers to say, "Well, my kid is too old to start this,” or even too young, and that's one of the reasons why with the book, it was really written based on the chronological development of children. I wanted parents and teachers and caregivers to understand what their child is experiencing, or, even as they get older, understanding about race and racism, so that they know how to engage or approach or counteract, or, more specifically, what they can do for that child at that age to raise them to be antiracist.

And, you know, studies consistently show that even if you're talking about older children who you've never had a conversation about racism [with], who you've never tried to ensure that they understand all the different racial groups as equals, that they understand that the racial inequities that they see are the result of bad policy and not bad people, if you start that conversation at 13 years old, or 17 years old, it's gonna have an impact, it's gonna have a lifelong impact. So, I just wanted to encourage caregivers of all kinds to understand that.

KO: And you definitely do. This listen is part memoir, and the opening is so vulnerable and powerful as you describe the racism that your wife, Sadiqa, faced while pregnant with your daughter and how, despite being a pediatric ER doctor herself, no one believed her when she brought up her symptoms. You also talk about your own parenting experiences, your parents' experiences with you and your brother, racism you faced as a child, and you just do a beautiful job of weaving these personal stories with history and fact. I'm curious about how you crafted the book. Did you start with your own journey and then bring in the data that underscored your experiences or was it the reverse?

IK: It was sort of both. I did a tremendous amount of research on the racial attitudes of children, almost as a foundation for the book to really understand how kids are understanding or experiencing race at one years old versus five years old versus 10 years old versus 15 years old. And the beauty is that scholars have been studying the racial attitudes of children for nearly a century. I mean, there was a book in 1929 called Race Attitudes in Children, and that book actually found that kids as early as five years old have what we now call bias towards people of what that intellectual called "outgroups." Since that time, it's been reduced to three years old.

"Research shows that to raise a critical thinker is to raise an antiracist, to raise someone who's empathetic is to raise an antiracist."

So, I wanted to collect that research, but then I also wanted to collect and really understand the research on different aspects of how we can take different routes to raising a child to be antiracist, whether that route is how research shows that to raise a critical thinker is to raise an antiracist, to raise someone who's empathetic is to raise an antiracist. I wanted to show parents the nature of the environment that they raise kids in has an impact. Nonverbal language has an impact. These are all the things scholars and scientists have been finding. I collected all of that research, but then side by side with that, I was sort of remembering and recalling and researching my own personal story. And then I had to put all of it together [laughs] and allow it to make sense, which, of course, was the hard part.

KO: No small task, I'm sure [laughs]. You've revealed that you were writing How to Be an Antiracist while you were battling Stage 4 colon cancer, and you thought that it would be your last literary contribution to the world. And here you are, years later, defying the odds. Can you talk to me about your mindset writing these two books versus that one, knowing that you still had more gifts to give the world?

IK: So, I think that the major difference, actually, between writing these two books, How to Raise an Antiracist and Goodnight Racism, and writing How to Be an Antiracist was really my mindset. When I was writing How to Be, particularly the last two thirds of the book, while I was battling cancer, I didn't feel any sort of pressure, in the sense that wondering what people would think about my vulnerability, you know, as an example, or the ways in which I challenged orthodox notions of how we define or understand racism. I wasn't worried about the response. And in a way, because I wasn't worried about the response, I think it freed me to, for the first time, really understand how to truly be as honest as possible about myself and my own imperfections, as well as be as honest as possible about the research and what the scholarship is saying, and be less concerned with what people are gonna say in response.

I think with How to Raise an Antiracist and Goodnight Racism, I, in a way, had to figure out a way to get back to that mind space, and I don't think it was actually that difficult, because of all of the scrutiny my work has come under over the last two years in particular. When you are under a tremendous amount of scrutiny, as I have been, you could either be just uber concerned with how all these people are going to respond or you can just be uber concerned about the manuscript itself.

And because almost all of the people who have attacked my work have not read my work [laughs], or who have misrepresented and distorted it, I was able to—like, I constantly sort of remembered that, and again was focused on being as clear as possible, as honest as possible, and standing as much on research as possible, as I was able to do with How to Be. But I had to get to that point, and in many ways, cancer thrust me into that point with How to Be.

KO: You share in the book the moment when your daughter, Imani, saw your bandages from your surgery. And that can be scary for her and for you, but in so many ways, it is easier to show physical scars than to show emotional ones from racism that you endured. Can you share with our listeners how you invite your daughter into those moments as well?

IK: I think that one of the ways we can do that is by when our children ask questions about racial inequality or about race, or they say things that we feel are inappropriate, which hopefully can prompt us to not shut them up, but actually open them up to a conversation. In those moments, we can be revealing about ourselves. And so, to give an example, recently my daughter was talking with my partner, who's a physician—the real Dr. Kendi—and whose mentee was graduating from medical school, and my daughter was watching the processional and watching the ceremony and at one point asked my partner, like, "Why isn't there more brown people here?" Specifically, looking at the graduates.

"One thing about kids that I love is they are rebels, and you take something out of a kid's hand, they're going to find a way to get it back. And so, if there's anything we want you to actually be a rebel about, it's books."

That, of course, prompted my wife to explain why and to talk about the bad rules that are keeping Black and brown people out of medical schools. But it also prompted her to share about her own personal experience as a physician, and I suspect she's gonna continue to have those conversations in which she reveals some of the things she's faced and she feels. So, I think those conversations, we should not only speak about the structural, we should not only speak about the policies. Or if we don't understand that, we should not just work with our child to study it, to uncover it, to read up on it, to go to the library about it, to learn about it. We should also, as we're researching it, or as we're reflecting on it, think about our own experience with that issue and share it.

KO: Yeah. Finding those teachable moments as they come up and not shutting down those conversations. I love that, and I think it’s something for all caregivers to carry with them. And speaking of your daughter, you do a beautiful—I've been saying your voice is like poetry on this audiobook narration of How to Raise an Antiracist, but your daughter, Imani, performs Goodnight Racism. What was that experience like for you both?

IK: I mean, obviously, I'm looking up to her and I thought she just did a magical job. As a newly turned six-year-old narrating Goodnight Racism and not just narrating it in terms of saying the words, but adding her personality and adding her emphasis to different things at times, I mean, it was, for me, it was an incredible experience. Probably one of the highlights of my career, to witness it and to participate in it and to see it, and to see her say, "That's my book." So, you know, it's no longer by Ibram X. Kendi [laughs]. And it's not by the real Dr. Kendi. It's by the real Kendi, Imani Kendi. And so, for her to take ownership of it and, you know, to love it, it's been a beautiful thing to witness.

KO: That's amazing. I love that confidence. "This is my book now." So, since becoming a parent, you've really evolved as a public figure. I'm kind of wondering now if Imani has to call you MacArthur Genius daddy, or maybe Daddy Genius, but anyway [laughs]…. How would you say your parenting journey has paralleled your professional journey?

IK: I think, well, first, I don't know if we talked to our daughter about the MacArthur Genius grant because then I'll have two people joking with me every time I do something that's not the smartest thing. "Oh, I thought you were a genius." I think it's one thing that my partner's saying that, but to have my daughter too [laughs]...

No, but in all seriousness, I think for me, it has actually directly paralleled my own career because when she was born in 2016, I had no desire or interest to write books for children. I could probably count on a single hand the number of picture books or board books that I had read front to back. I did not have any nieces or nephews or, you know, very small cousins who I was a primary or a main caretaker of, and so being my first child and not necessarily surrounded by a lot of very small children, more so older children, it was a new experience in so many different ways.

And one of the ways was, I became the person who was primarily choosing and reading the books for Imani. And the more books that I read for her, the more I started thinking, “Maybe this is something one day I could potentially do and that it would be great to create a book for her, or for other kids like her, or for kids who are not like her.” And, obviously, that first book became Antiracist Baby. And, ultimately, I subsequently partnered with other writers to write books for middle graders and young adults and ultimately Goodnight Racism, my picture book, and of course this guide for caregivers in How to Raise an Antiracist. And I just don't think that these books would've come to pass if I hadn't become a father.

KO: That makes sense, and I'm sure as you two continue on your reading journey together over the next decade or so, maybe we can expect even more where that's concerned. But speaking of books for young people, I was surprised to learn that you almost dropped out of high school your freshman year. You say that the only thing that was keeping you in was the wrath of your parents. And then later, in your senior year at a different school, you were, quote, “tossed out” of your IB English class, and you thought you hated reading, but really you were only exposed to white authors. And there are so many wonderful YA books by authors of color, many of which you mention in your book, but, unfortunately, so many of those stories and those authors frequently have their books banned—like Angie Thomas, like Nic Stone—and that is sending a message that these books that feature main characters of color are somehow dangerous. What is your advice to kids who are living in regions that are getting hit particularly hard with these book bans?

IK: I think my advice, for kids especially, is if you want a reading list, then find out what books are being banned by your school, by your library, by your state. One thing about kids that I love is they are rebels, and you take something out of a kid's hand, they're going to find a way to get it back. And so, if there's anything we want you to actually be a rebel about, it's books. I think that obviously there's been a lot of ink spilled and a lot of conversation about the banning of books. But, I mean, when we really unpack it and we really think about what it means to ban books, of all things. I mean, it is just unconscionable.

"If there's one group of people who can break that circle and bring us out of it, it's young people."

But then again, as an historian, it sort of harkens back to the Jim Crow era, when books that did not espouse white supremacy were banned in the Jim Crow South. Or it even harkens back to the enslavement era when enslavers, to quote one person at the time, “legislated for ignorance.” And it wasn't just ignorance of enslaved people, even ignorance of non-slave-holding whites in the South. The power of slaveholders directly relied on the ignorance of people who were not enslavers or people who were enslaved. And so, the fact that we've come full circle, in which we have people still legislating for ignorance, is a travesty. But if there's one group of people who can break that circle and bring us out of it, it's young people.

KO: I think that's a great transition to my last question, which is about optimism, because it is a hard time to be optimistic, but the very premise of this book is an optimistic one. There is so much hope in this next generation. How do you personally maintain your own hope when we have so much tragedy happening around us?

IK: I wonder if that's one of the reasons as well that I've gravitated to working with and thinking about and writing for young people and writing for caregivers who are engaging with young people. Because to work with young people, to think about young people, to write for young people, to think of just the [imagination] of young people, to recognize that young people don't have the baggage that adults do about race, to see the studies and see it for ourselves how young people are very clear about right and wrong, justice and injustice, fairness and unfairness, all of that sort of gives me hope. All of that keeps me hopeful. And it wouldn't surprise me if the people who are regularly engaging with children—whether their own children, whether students, whether nieces and nephews, or patients, as pediatricians or medical providers—are the people who are the most optimistic in our society.

KO: Yeah. There is such an innocence there, and then the justice, too, between the right and the wrong. I see that a lot in my own parenting experiences. They have a very strong belief in what is right and what is wrong, and it's up to us to ensure that those conversations translate to the larger world around them. So, thank you for your time today. It was a privilege to speak with you.

IK: Of course. A privilege to speak to you. Thank you so much.

KO: Listeners, you can get How to Raise an Antiracist and Goodnight Racism right now on Audible.