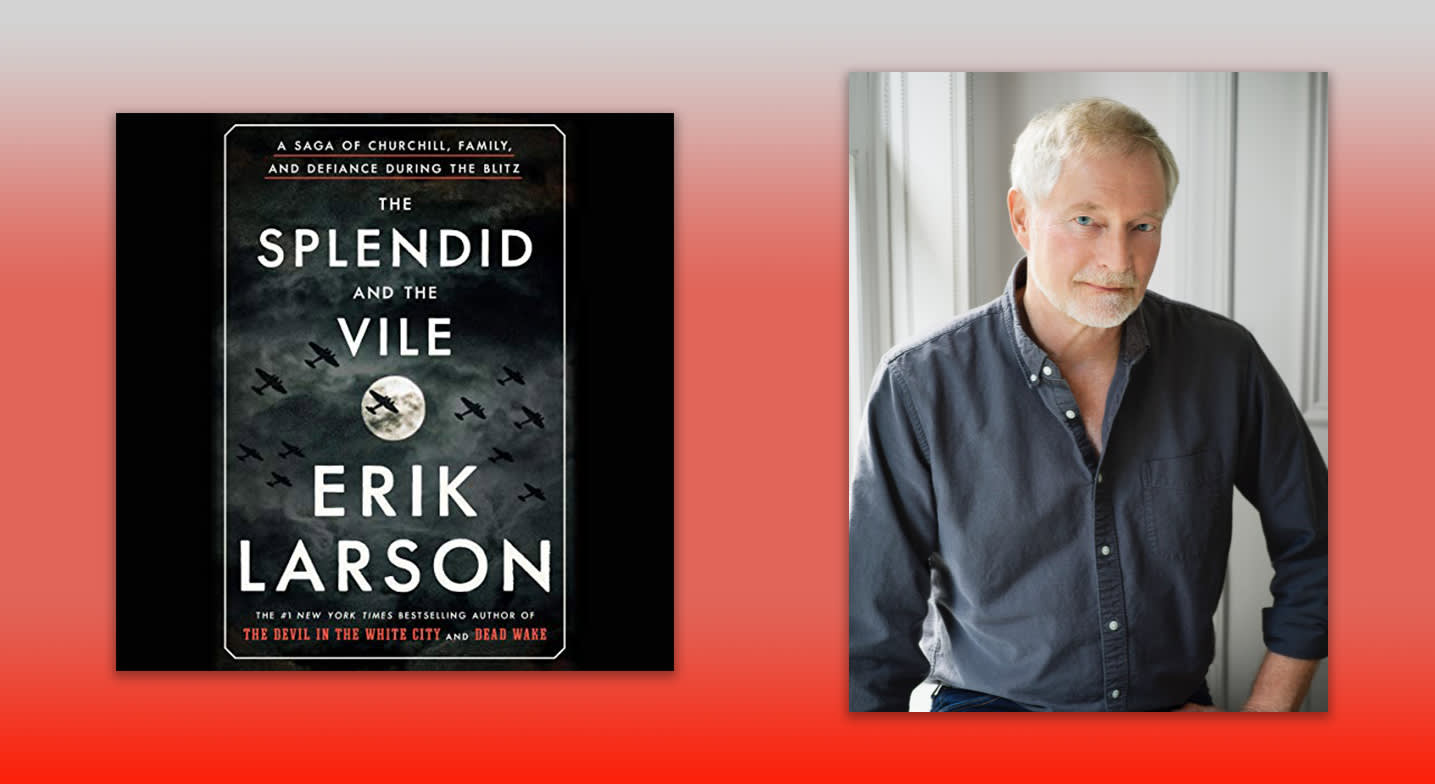

Editors’ note: A lot has happened in the world since we interviewed Erik Larson just a few weeks ago. Our busy, moderately anxious lives have been upended by a global pandemic, leading to isolation, economic turbulence, and higher anxiety than ever before. And yet Larson’s new audiobook The Splendid and the Vile — a gripping saga of the first year of World War II, set during the Blitzkrieg — is even more relevant now. The true story of Winston Churchill’s leadership through one of history’s biggest crises offers a window into how the British prime minister famously steadied the nerves of his people and united them so they could “keep calm and carry on” in the face of extreme adversity.

Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

Kat Johnson: Hi there. I'm Audible editor Kat Johnson and I am thrilled to be speaking with bestselling author Erik Larson today. Erik's works of narrative nonfiction take historical events and turn them into immediate and vivid experiences, and his latest book, The Splendid and the Vile, about Winston Churchill during the blitz is no exception. Erik, thank you so much for joining us today.

Erik Larson: I thank you for talking to me.

KJ: Absolutely. I can't wait to dig into this with you. You have such a knack for turning these historical subjects that we think we know so well — like the sinking of the Lusitania, H.H. Holmes, Hitler — into these sort of modern thriller-like suspense stories with incredible crossover appeal. I'm curious, was Winston Churchill and the blitz, does this feel like that for you? And, and how did you land on this subject? What convinced you to write it?

EL: Whenever I'm thinking about the next book idea, it's always story-driven. It's the story that drives me, not necessarily the subject matter or the era. This was not desire to, "Oh God, someday I have to write about Winston Churchill." Rather, this thing arose kind of organically, if you will, from a move that my wife and I made from Seattle to New York city. We had been living in Seattle and it got kind of quiet for us when our three daughters moved off, and we'd always wanted to live in Manhattan. So we moved. And what happened, really virtually upon arrival, I had this kind of epiphany about 9/11. You know, in Seattle we, of course, had watched the events of that day unfold in real time. It was, of course, horrific, and like millions of others we had watched this whole thing.

But then when I got to New York I realized that the experience of New Yorkers was completely different. So radically more vivid, not just in terms of sounds and sights, but also in that sense of violation of having your home city attacked. I started thinking, "What would that have been like in London during the air campaign by Luftwaffe, especially the first phase of that campaign, the first phase against London, when the city experienced 57 consecutive nights of bombing in a row? How does anybody endure that kind of thing?" So that question led me then to think, "Well, this would be something to explore in a book. Maybe I could look at a typical London family and see what their experience was like." Then I started thinking, "Well, what about not a typical family, but the quintessential London family: Churchill and his family and his advisors. How on earth did they do it when Churchill also happened to have to be running his half of the World War?" So that's how the story came about.

KJ: That's fascinating. And it's so interesting because you bring the family to life so much. And in fact, we have an editor's podcast where, for our February episode we were talking about relationships, and I thought, "Actually Winston Churchill and Clementine's relationship was actually kind of one to aspire to." I learned so much about their relationship in the story, and I was wondering since you're a father yourself, did you think about how it's so hard to parent through stressful times. Did you look to Winston Churchill at all for any kind of parenting tips?

EL: Well, I absolutely. The fact that I am a parent absolutely informs this book. My daughters are grown, as I said. There are two in their 20s, one in her 30s, but they still accuse me of being the king of anxiety and transferring my anxiety to them. But my anxieties are quotidian anxieties. It's like, what about their smoke detectors? Do they wear their seat belts when they drive? What about their boyfriends? Do they have the right boyfriends and all that kind of thing? You think about Winston Churchill, the same kind of fatherly concerns, especially in the case of his youngest living daughter, Mary Churchill, who was 17 at the time he became Prime Minister and when the action begins in the book.

So, if you're Winston Churchill, you have all these anxieties, and you have also everything else going on. I had to marvel at how he was able to pull all of this stuff together. And not just him, but also Clementine, who of course was Mary's mother and the mother of the other grown children. And how did they actually manage all this?

KJ: Absolutely. I'm glad you brought up Mary because she was absolutely one of my favorite characters to hear about. You were able to read her diary, right? You said in the introduction that all the dialogue, everything is sourced really from the historical record, and you use these primary sources.

EL: Right.

KJ: Can you tell me a little bit about how that works? Because to me, that's bananas. It's overwhelming.

EL: Yeah. Let's talk about Mary, in the context of Mary. So Mary Churchill, again she was the Churchill's youngest surviving child. They had lost a daughter, Marigold, when she was very, very young, two years old, if I recall correctly. But so here's Mary. Mary is 17, and Mary kept a daily diary of her life as one often did back then. But Mary was a particularly observant and articulate young woman. Her diary is just full of observations about the times, about her father, and also about the fun stuff of her life. She makes reference of snogging in the hay loft and hanging out with RAF pilots, and periodically these RAF pilots from a nearby RAF bomber base would come flying over at treetop level just to thrill the girls. It was that kind of thing.

But also, Mary chafed at being sequestered, if you will, by her parents at the prime ministerial country home, Chequers. They wanted her there for safety. She wanted to get back into the action. She wanted to come into London and share the hardship. She wanted to be part of the war. So there was that very interesting tension there. And so she provides this lovely sort of, not exactly a Greek chorus, but this counterpoint to all the large world events and the chaos going on at the time, and I was very lucky to be able to read and use the diary, because at the time I got permission from Mary's daughter and the sons to read the diary, I think I was like one of two scholars who had ever looked at it. So I felt very much blessed by the opportunity. And she is absolutely my favorite character.

KJ: Oh, that's so great. And it's amazing because I'm so glad that she kept a diary, but I also kept thinking she would also be an amazing Instagram follow if she was around today. As you say, just going out and then moving to 10 Downing Street.

EL: Yeah, she really would. But believe me, any of these characters would have been a great Instagram follow, if, of course, it existed at the time. But you're right. She especially.

KJ: Yes, absolutely. And in general, I mean the diaries, the historical record is so incredible to me. Was everyone in Europe keeping a diary at the time, or how did that work?

EL: You know, you get the impression actually that everybody was keeping a diary, but no, obviously that's not the case. It is, however, the case that Britons of a certain era and a certain class were a supremely well-educated and articulate bunch, and some of these diaries are really, really a wonderful read, even just beyond their historical value. One diary was illegally kept by John Colville, who was one of the Churchill's cadre of private secretaries. And that really gives one of the most vivid, detailed, and intimate views of life at 10 Downing Street that has ever been produced.

So there's that diary but there are so many others by ministers – ministers as in government officials – but ministers and generals and American observers and so forth. It's really almost an embarrassment of riches that I, as a researcher, get to go through because it's more a question of picking the best stuff rather than having to find anything, having to scrape up something from fallow earth. There's just so much great stuff in these diaries.

And actually, along the lines of these diaries, one of the most amazing things that I came across, and this is not news to anybody who's spent a lot of time in studying this era, but to me it was this entity called Mass Observation. This was a social sciences organization that was founded before the war to try to come to understand what ordinary British life was like. As the founders said, it was to create a social anthropology of ourselves. So this organization, Mass Observation, recruited hundreds of civilians to keep daily diaries of just their ordinary lives, and then submit them on a regular basis to this organization, Mass Observation.

So along comes the war, and a lot of these people will still keep their diaries, which provides this amazingly intimate look at what life was like during the war. I mean, talk about a boon to research. There's one diarist in particular that has a significant cameo role in the book as sort of a counterpoint to give an indication of what the London Everyman/Everywoman would be experiencing. This was a young woman named Olivia Cockett, who was a police clerk that clerked with Scotland Yard, who was carrying on an affair by the way, with a married man. And she was not at all shy about detailing elements of that as well, which makes it a particularly charming diary.

KJ: That's the good stuff, right.

EL: That's the juice. But she chronicles her experience of the war in a way that I think really opens a window into what life was like. It provides a lot of insight. For example, it starts during the first deliberate attacks on London, and it took a while in 1944 for the Luftwaffe to come around to finally deciding, "Okay, we're going to bomb the hell out of London." So the bombings of the cities start in, it's obviously terrifying for people and terrifying for Olivia Cockett. But then one day an incendiary bomb falls outside her home. Incendiary bombs were what the Luftwaffe dropped first to set fire to things. The fires would then be used as a beacon by the bombers to follow, which would then drop high explosive bombs. So this incendiary bomb landed outside her home, and she put the incendiary out. She snuffs it out, and this just emboldens her. She is just so thrilled and having done this that it completely changes her life.

I mean, she becomes this courageous young woman who just really wants to do everything she can to help with the war effort. Meanwhile though, her boyfriend, this married man, is becoming more and more cowardly and this drives her nuts. She cannot tolerate this. And one of my favorite little moments is when they're walking along in a raid, as one does, they're walking along during a raid, and when they hear two bombs about to fall near, this guy Bill shouts, "Get down," and Olivia's response is, "Not in my new coat, I'm not."

KJ: I can relate. That's highly relatable. And I think that's what's amazing — because you had access to these first-person accounts and from the very first page you're capturing this tremendous sense of anxiety from everyday people that's just pervading London at the time. I feel like we're kind of living in an era where everybody feels like we're so busy. Our age is characterized by anxiety. Are you like, "We just don't know the half of it"?

EL: Well, our age is characterized by anxiety, and unfortunately, it's an era where that anxiety is fueled and fanned by the top office in the land. It's funny when I was working on this book, this started five years ago before the current political malaise and there's absolutely zero political agenda in it. But I did find that as I was going along doing my research that I found solace by sort of psychically going back to this era, to the clarity, the heroic clarity, to all that was happening in Churchill's leadership and so forth. And, and I started to think to myself more recently, it's like, "Now, if I'm going back to this era of mass death, chaos and horrific events and I'm finding solace there, it must be pretty bad here."

I think if there's a takeaway for our contemporary audience, I think it does not hurt in any age to be reminded of what real leadership can look like. And no matter what you think of Churchill, the fact is he was indeed a real leader. He's a terrible tactician, terrible strategist, but he was a true leader. He understood the power of symbolic acts. He understood the necessity for unifying people and also for emboldening them, for helping them to find their courage, but also being very candid and very direct. It was this very important mix that helped to help Britain get through this.

KJ: Yeah, I mean he's really known for that. I'm curious, looms so large in our imagination as having these amazing oratory skills and this incredible stubbornness. I think his motto was keep buggering on, as they say in the book.

EL: I don't think I say that in the book. One always has to footnote. One always has to be careful about quoting Churchill, because probably about 75% of things that are attributed to Churchill were never said by Churchill. But just the fact that all these things are attributed to him is an indication in itself of how much of a leader he is perceived to be.

KJ: Right, absolutely. And do you find that those characteristics of his that loom so large in our imagination, does that kind of overshadow some other interesting things about him? Is there anything that you learned about him that was, I don't know, new to you or interesting to you?

EL: Well, yeah. I'm big into nuance and context, and yes, there is Churchill, this leader, but at the same time, one has to avoid the impulse toward hagiography, and yes, I am actually pronouncing that correctly. But yes, because Churchill did not win this war alone, and that's really a big, big point about the book. That as much of a leader as he was, he relied heavily on those around him for comfort, for distraction, for counsel, be it a family member like Clementine or be it his key advisors, his science advisor the prof, Frederick Lindemann, who shared his adoration of secret weapons, or Lord Beaverbrook, a newspaper magnate who kind of saved the day by taking over the manufacture of aircraft and really ramped it up.

But who was also this cataclysmically capricious and energetic character. Another thing about Churchill that I think is important to note in terms of leadership is that he did not want yes-men. He did not want loyalists. I mean, it didn't hurt that they were loyal, but what he wanted was people who would tell, would speak truth to power, like in the case of Lord Beaverbrook. He knew that this man would be a source of conflict in his government and he wanted that. He wanted that. So that's another example of the kind of leadership. But back to the question at hand about nuance, it was also the reality that Churchill's staff found him to be at times incredibly inconsiderate, rude, overbearing, but at the same time they loved him.

I know that one reason they loved him, and actually this is the biggest surprise to me in my research, was because Churchill was a lot of fun. He was a lot of fun. He had a great sense of humor. He loved to sing his favorite songs like Run Rabbit, Run, Run, Run, Run, Run. Count the number of runs. I think there's like five in the title of that song. But anyways, Run Rabbit, Run, Run, Run, Run, Run and songs from The Wizard of Oz, Gilbert [and] Sullivan, and so forth. I mean he was just a lot of fun to be around and he was able to compartmentalize things so that if he dealt with something tragic or awful or something that really annoyed him in his government, he could sort of put that in a box. And then the next box you can be funny and kind and he had this way of just offering this baby-like smile that just caused people to absolutely melt.

KJ: Right. And he was kind of an eccentric as well. One of my favorite anecdotes in the book, and I know because it's in your book someone did say that this happened, he received President Roosevelt completely naked and holding a cigar and a glass of Scotch or something.

EL: Yeah, yeah. That's a moment toward the end of the book when Churchill and company visit Washington and Churchill is staying actually in the White House and President Roosevelt wheels himself over for a chat and Churchill's bodyguard, Lyle Walter Thompson, opens the door and there's Roosevelt. And as Thompson is at the door looking at Roosevelt, he sees this funny look come over Roosevelt's face as Roosevelt then starts to wheel the chair backward as if sort of metaphorically saying, "Well I'll come back another time," because behind Walter Thompson there's Churchill stark naked. And then yeah, I believe he has a cocktail in his hand and maybe probably also a cigar. But so, and I'm going to fracture this line, but Churchill says something to the effect of, As you can see, the Prime Minister of England has nothing to hide.

KJ: Right. That's incredible. And that one we know he did say, or his secretary did say that.

EL: Oh yes. Yes. Not in those precise words. There are a number of accounts of that sort, but they all are essentially, the gist is the same — that I have nothing to hide.

KJ: Oh, that's fantastic. I want to switch for a second to the narration, because you've worked with a variety of narrators for your audiobooks, and this one, I don't think you have anything that's been narrated by John Lee before, but he's so perfect for this. Did you have any insight into that process or any influence in that process?

EL: No, I did not have any input into the process. My feeling is that producing audiobooks is an art form. I am a writer. I have my art form, narrative nonfiction. And people who produce audiobooks, that's their art form, just as somebody who does screenplays or movies, that's what they do. And I am not sufficiently arrogant to presume that I have any great insight into how one performs those acts. However, interestingly, one of my daughters for a time produced audiobooks for Simon and Schuster. She now does podcasts for Spotify. But she would cue me into all this interesting stuff about producing audiobooks and about voices and so forth. And also about the fact that as an audiobook producer, she really doesn't necessarily like it when an author reads his or her own work because it's much more involved and much more difficult, lots of redo’s and so forth. But John Lee I think is perfect choice. Absolutely.

KJ: Yeah, I agree. I'm not a professional at producing audio books, but I am a professional at listening to them and critiquing them, and I think this is a fabulous choice.

EL: That's good to know.

KJ: His Churchill impersonation is great.

EL: How do you like the little Churchill ender?

KJ: Oh, it's great. I was going to ask about that because I don't think that's referenced in the printed book, but there is that wonderful speech from Churchill right at the end. You chose that one, I assume?

EL: Yes, but it is referenced in the book but, not of course, as much detail. I do talk about the Christmas speech in Washington, but then, and actually while I say I don't want to get involved in audio books, that's somebody else's turf. I have to say, this is sort of my idea was that why didn't we try to get a Churchill doing the speech himself? It's quite a moment captured by a newsreel crew of him standing there in the south portico at the White House delivering this speech on Christmas Eve, 1940. Very, very moving moment. So I was thinking it would be nice if, after the book comes to an end, somehow make this transition to this live speech and get out of the audio book. Now, having said that, getting the rights to the speech was really difficult because Churchill and the Churchill family and so forth have a lock on a lot of Churchillian materials, including speeches and letters and so forth.

KJ: Got it. Thank you. All right. I want to ask, because I come to your work through my love of true crime so I am a huge fan of Devil in the White City, as well as Dead Wake. But I also have a husband who, like many men, is just obsessed with, has a bottomless obsession with World War II.

And I guess through my love of true crime, we kind of grapple with the fact that we're constantly rehashing stories about the same serial killers over and over. And I sometimes feel guilty about this, but then I kind of think they're like classics in a way. They're almost like archetypes that allow us to kind of process new questions through these same stories. I'm curious from you, is there something about World War II that you think serves this function, or why does it endure with us so much as opposed to some of the other wars or any other historical event? Because it's really quite overwhelming I would say.

EL: Well, I have to parse that a bit. I mean, to me, of course, World War II is infinitely interesting, but it's not something that draws me to do books on the era. I am totally story-driven. If instead of moving to New York and having this 9/11 epiphany, I had had some other experience that pointed me at Ponce de Leon, I might have had a book about Ponce de Leon. I'm interested in the story, and that's what brings me to a particular era and to particular historical characters. It's never the other way around. It's not like, "Oh God, I would love to write about Churchill someday. This might be the way." However, having said that, undeniably World War II continues to have this incredible appeal this far out in time.

I think a big part of it is that there is, whether true or not, there is a certain element of heroic clarity. That is, it's the good guys versus the really, really, really bad guys. I mean, nobody's worse than Hitler in that crowd. They were bad beyond bad. And then you have somebody heroic, like Churchill who, he's no saint. Churchill was Churchill. There are people who loathe Churchill for some of his policies in other realms, but there is this sort of perception of good versus evil, you know? And there's something very satisfying in that, in seeing the bad guys get whooped. And there's just sort of this classic powerful narrative in World War II. You know, darkness descends, the Allies are on the ropes for a good chunk of things, and then suddenly things start to turn, and then the bad guys are on the run. You know, it's a very, very satisfying primal story.

KJ: Yes, absolutely. And, but again, like your work, I mean we're discovering it anew, I think, through The Splendid and the Vile because I've never seen it tackled quite this way, so I so appreciate it.

EL: Good, good. I should tell you that before I set out on this thing, I had lunch with a guy who at the time was the head of the International Churchill Society. And I should note, by the way, that for this book, because it is about Churchill and when one wants to be absolutely correct, I actually had a professional factchecker go through the book and I also gave it to three prominent Churchillians, including this guy, to read, just to make sure I was really, really, really getting it right. So I had breakfast with this guy in Washington, DC, and he was kind of wondering why was I trying to do this? What was my hope, in terms of trying to say something new about Churchill, and I just told him, I said, "It's all in the telling. It's all in the telling."

And also, looking at that world through a particular lens, meaning a particular question that I wanted to answer. And when you do that, you are going to find new stuff because it's material that other people didn't particularly care about or overlooked. And you will also look at things that other scholars have looked at and you will look at it in a new light, in a new context and that brings a certain amount of freshness back to the story.

KJ: Right. And since you brought it up, are there any historical stories that you're obsessed with that you might never write about but you can share with us, because I'm so curious the things that you're interested in?

EL: Yeah. Well, first of all, if I knew what my next book was going to be, I wouldn't share it, but I don't know what my next book is going to be. But there are things that I am fascinated by and I would love to write about, but I can't and won't because I have certain criteria for books. One thing about narrative nonfiction is, you have to have a really rich, deep archival base if you're going to do it because obviously you can't fake it. You can't have composite characters and made up dialogue and all that stuff because then you entered the realm of fiction. But one subject that is eternally fascinating to me, frankly, is Pompeii, but I can't write a narrative of Pompeii because I don't have the narrative materials. I don't have the diaries. I don't have the nitty gritty government reports after the disasters showing everything that went on. So that will be eternally beyond my grasp.

KJ: Oh, fascinating. Oh, thank you so much. It's been so great to talk to you, Erik Larson, about your new book, The Splendid and the Vile, available now on Audible. I thank you so much for taking the time to talk with us today.

EL: No, thanks for letting me do so. Thank you.