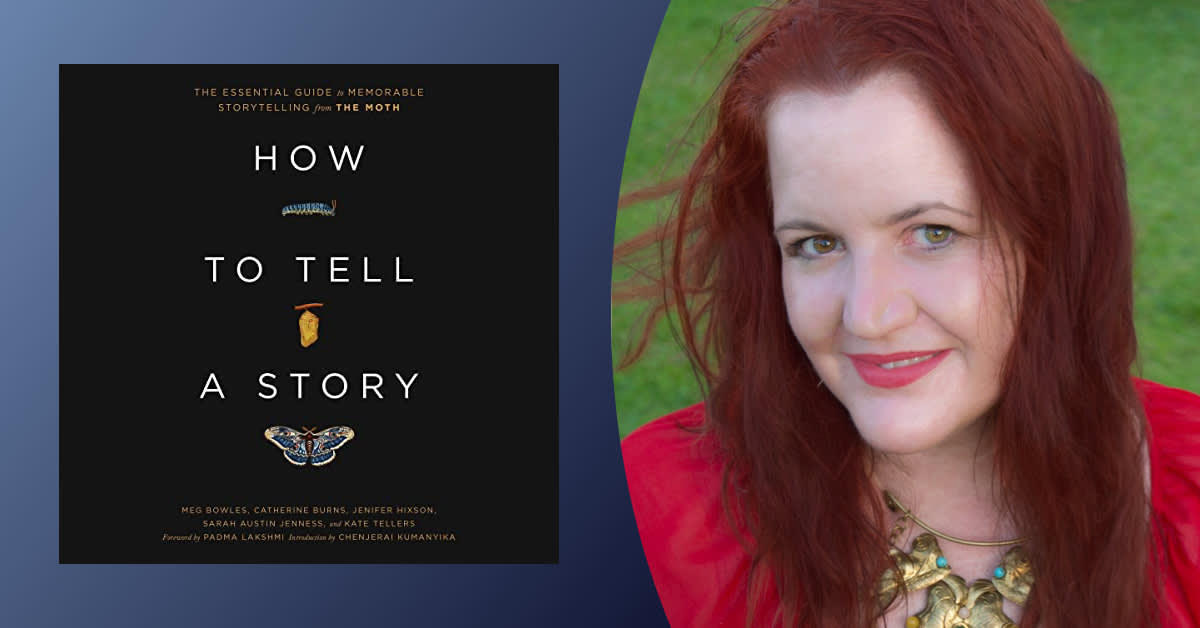

Being a compelling speaker can feel like something beyond your control—either you have the gift or you don’t, right? But that’s not true at all. Anyone can learn to be a great storyteller, and The Moth, a nonprofit organization that has been nurturing storytellers around the world for more than 25 years, knows how to teach you. With the appropriately eloquent guide How to Tell a Story, The Moth outlines their tried-and-true method for finding and telling a great yarn, which can be applied to almost any situation in life—job interviews, wedding toasts, eulogies, parties, meetings, you name it.

Being a better storyteller allows you to connect with others more deeply, and The Moth's creative director and How to Tell a Story coauthor, Catherine Burns, knows just how important that is. And as a mutual admirer of the power of voice, she recorded her answers just for us—click play below to hear them narrated in her own voice.

Catherine Burns introduces herself.

Catherine Burns: Hi. My name is Catherine Burns. I'm the artistic director of The Moth and a co-author of the new book, How to Tell a Story. I'm going to be answering a handful of questions for Audible.

Audible: What is The Moth's view on the power of oral storytelling and the human voice?

CB: Storytelling goes back thousands of years, from people sitting around the campfire conveying what happened during their days. It's extremely powerful to hear directly from a fellow human being, listening to their voice, versus all this digital media. The Moth is actually one of the very, very first storytelling organizations out there—we've been around for 25 years, and kind of grew up hand-in-hand with email and computers and the digital world. There are now thousands of smaller storytelling organizations, and I don't think there's any doubt that the reason for what I think of as this modern storytelling movement came up hand-in-hand with the digital age is because, even as we were drawn into our little devices and just talking through screens in this brand new way, there was a strong desire to sit in an actual room, next to actual breathing people, and listen to a single person tell a story.

To hear directly from that person, versus a big movie, where, even in an Indie film, it could be dozens of people on set to tell a story. At The Moth, it's just one person on stage, talking into a mic. You're hearing directly from the person to whom the story happened. And there is so much power in that.

What makes a good storyteller?

Audible: What makes a good storyteller?

CB: The number one quality of any great Moth storyteller is their willingness to be vulnerable. People think that we're gonna say, "Oh, it's a person who made a great speech at their high school graduation or someone who's really funny." Look, it's great to be funny. It's great to be the funniest person in the room, but the most successful storytellers by far are the ones who are willing to be vulnerable, who are willing to dig deep, to talk about things that are painful for them, to talk about the time they messed up or things didn't go so right.

"It's great to be the funniest person in the room, but the most successful storytellers by far are the ones who are willing to be vulnerable, who are willing to dig deep, to talk about things that are painful for them, to talk about the time they messed up or things didn't go so right."

You hear a lot of people telling stories, especially at parties, where they're bragging, they're talking about being the smartest person in the room and the time they saved the day. Ugh, we actually find this a little bit boring (laughs). The most interesting stories are about somebody who had a puzzle they were trying to solve, or an issue in their life. Especially if you're willing to tell a story about a time that you messed up or when something went wrong. Our missteps are what make us most interesting in the world, and I think it's our foibles, if you will, that actually connect us most deeply to each other. When you hear someone talk about a mistake they made or a problem that they had, you think about your own problems. And I think it's easier to feel close to them, which is a way that storytelling can connect us in such a beautiful way.

What would you say to someone who doesn't consider themselves a good speaker but wants to share their story?

Audible: What would you say to someone who doesn't consider themselves a good speaker but wants to share their story?

CB: I would say, "Just be yourself." I feel like this is sort of annoying vague advice, but what I mean by “be yourself” is just whoever you are when you're sitting across from a close friend at dinner telling them a story, that is who you want to be, especially if you're telling a story at The Moth.

If you're worried about even not being a great storyteller over dinner, I would say, "Don't try to be somebody you're not." If you aren't somebody who tells a great joke, don't tell jokes in your story. Don't go out and memorize a bunch of jokes just to have something to say. Most people I know have some sense of humor and can convey that something happened that was humorous. So, when you're doing your story, just convey it in that way, but don't try to just throw in jokes for the sake of jokes.

One of the few ways you can not do well at The Moth is to be super joke-y. We occasionally will have a great standup comedian who comes in and instead of wanting to really tell a story and be just a funny storyteller, they'll want to take a string of jokes and find a story that will tie them together. But really, the story is there to just support the string of jokes and that is never successful.

The best stories are where the actual story, what happened to you, is front and center, and if there's humor in it, it's just there to support the story. You always want your jokes to be organic to the story.

How do you mine your memory to choose a story worth telling?

Audible: Walk us through your process. How do you mine your memory to choose a story worth telling?

CB: When people don't know what story they want to tell, I often say to them, "What is a story that you can't wait to tell a new friend? What is a story you can't wait to tell if you have a new boyfriend or girlfriend?"—because we all tend to have those. Now, sometimes they're anecdotal. Sometimes it might be something that's just like a little funny thing that happened.

But if you want to be a better storyteller, one thing to think about is of these little tidbits that we tend to tell over and over at cocktail parties, if you are willing to dig a little bit deeper, usually you can find that there's something about that tidbit that speaks to who you are in a bigger way. If you think about who are you at the beginning of that thing happening, and who are you at the end of it, you'll find that there's some shift it created in you, and that there's a reason why you're telling this tidbit again and again. I say tidbit, but also the word we use in the book is “anecdote.”

I'll give you an example from my own life, one of my most repeated anecdotes, a story that friends will ask me to tell—that's another way to look for a story. What are the stories that your friends ask you to repeat to their friends when you meet them? One of mine is how, at my rehearsal dinner for my wedding, the restaurant double-booked our wedding rehearsal dinner with an actual wedding. They thought they could get us out in time, but the two things overlapped. It turned into a totally crazy situation where [the people in] the other room were screaming and actually threw chairs and broke things.

I can just tell that in kind of a breezy funny way if I have two minutes, but the truth is, I was from a very Christian, Southern family. My husband is from a Jewish family that's always lived in the greater New York City area. And we were nervous about how these two families were gonna come together. And when this kind of mini disaster took place—humorous in hindsight, but at the time, not great—it became this bonding thing for the two families. Now they had this shared story and everyone went out afterwards laughing about it and talking about it. And it actually created just such a warm feeling the next day at the wedding. I should also tell you, we got out of the restaurant very quickly, and the other couple's wedding went on and was completely fine, so it all ended well. But it actually is the thing that bonded our families, that we all still laugh about all these years later.

So, you can see, hopefully, what I did there. It's just this little anecdote about a wacky thing that happened. But if I just dig into it a little bit, you can see that the stakes are raised when you understand how nervous I was for my family to be meeting my future in-laws. You know, it actually became a huge bonding thing for me and my mother- and father-in-law because they were technically throwing the dinner and they were very cool about everything that happened. They could've been real jerks and thrown a fit, and instead they were just so warm and supportive. It really made me love them. In fact, at one point, I looked up at my future mother-in-law, who was actually comforting the other bride, and it just made me fall so deeply in love with her. And we're very close to this day.

That's just an example of how you might mine a small memory, but try to think about [how], even if we're telling it at a party, you could set that up a little bit with the families, because then it does raise the stakes. And when I say raise the stakes, what I mean is ... you want to convey to the listener why you're choosing to tell the story right now. Why you care. Sometimes we say at The Moth, "Who are you at the beginning of the story? Who are you at the end? And why do I care?"

I'm joking with “Why do I care?” But what I really mean by “Why should I care?” is why do you care? If you can convey to us why you care, it's gonna make a much better story because then we're going to care for you.

If we're the teller, how do we know when we've achieved true connection with someone else?

Audible: If we're the teller, how do we know when we've achieved true connection with someone else?

CB: I think one way to tell that your story has landed is if the person listening will say that the story made them think of something that happened to them. Because that means that they're connecting with you in a deep way, that they're feeling your emotions in the story, and it's bringing out emotions of their own, which is making them think of things that happened to them. So, if you're telling a story and the person comes back and tells you a story or tells you that it reminds them of X, Y, Z in their own life, that's a sure sign that you're connecting with your listener.

How do you think we can be better listeners and more receptive to others' stories?

Audible: How to Tell a Story is focused on the outward process of telling a story, but on the other side of that is the listener. How do you think we can be better listeners and more receptive to others' stories?

CB: If you want to be a better listener, one tip is to ask questions. Listen along, don't interrupt, but if you have questions, ask them because it shows that you're listening. And if you're trying to form questions, it indicates to the person talking that you are actually paying attention to what they're saying and want to know even more.

"It's such a rewarding experience to actually stop and listen to someone in a deep way, because we're so often rush, rush, rushing through life."

That is one way to think about how to be a better listener. I also just say that the greatest quality of any Moth director—we actually coach and direct the stories—is someone who's incredibly curious. So when you're listening to someone tell a story, try to approach it with curiosity. Often in the modern world, [there's something] our founder [George Dawes Green] was struck by when he first got to New York City in the late 1990s—it was just like cocktail party chatter. And he felt like nobody was actually ever listening, that people were just waiting for one person to stop talking so they could jump in. So instead of doing that, try to actually pay attention to what the person is saying. Formulate quick questions and just be quiet and listen.

Approach what they're saying with curiosity because it's such a rewarding experience to actually stop and listen to someone in a deep way, because we're so often rush, rush, rushing through life. And it's important sometimes to stop and slow down and think about life, and think about how life is affecting us, and how it's affecting the people around us.

Where are you hoping we'll go?

Audible: What do you think is the future of storytelling in our hyper-connected and globalized world? Where are you hoping we'll go?

CB: I am just loving the rise of audio being such a thing after such a video-centric world that we've been in since, like, through the 1960s, '70s, '80s. We're seeing it go through the roof, with the popularity of podcasts.

I'm also noticing that my friends are starting to leave me voice texts. They do a voice recording and text it to me and I'll listen, and then I speak back. And I am loving it. I hate thumb typing (laughs). There's just something so warm and generous about hearing a friend's voice. And what I would love to see is to find a way for audio to expand around the globe in a bigger way.