We know we shouldn't judge a book by its cover...or its title. But from the minute we heard about the debut novel My Sister, the Serial Killer, we were in and wanted to know more. Imagine our delight upon finding out that this unique tale about two sisters in Lagos, Nigeria--one of whom has a nasty habit of killing boyfriends, while the other is self-tasked with cleaning up the mess--more than delivered on its promise.

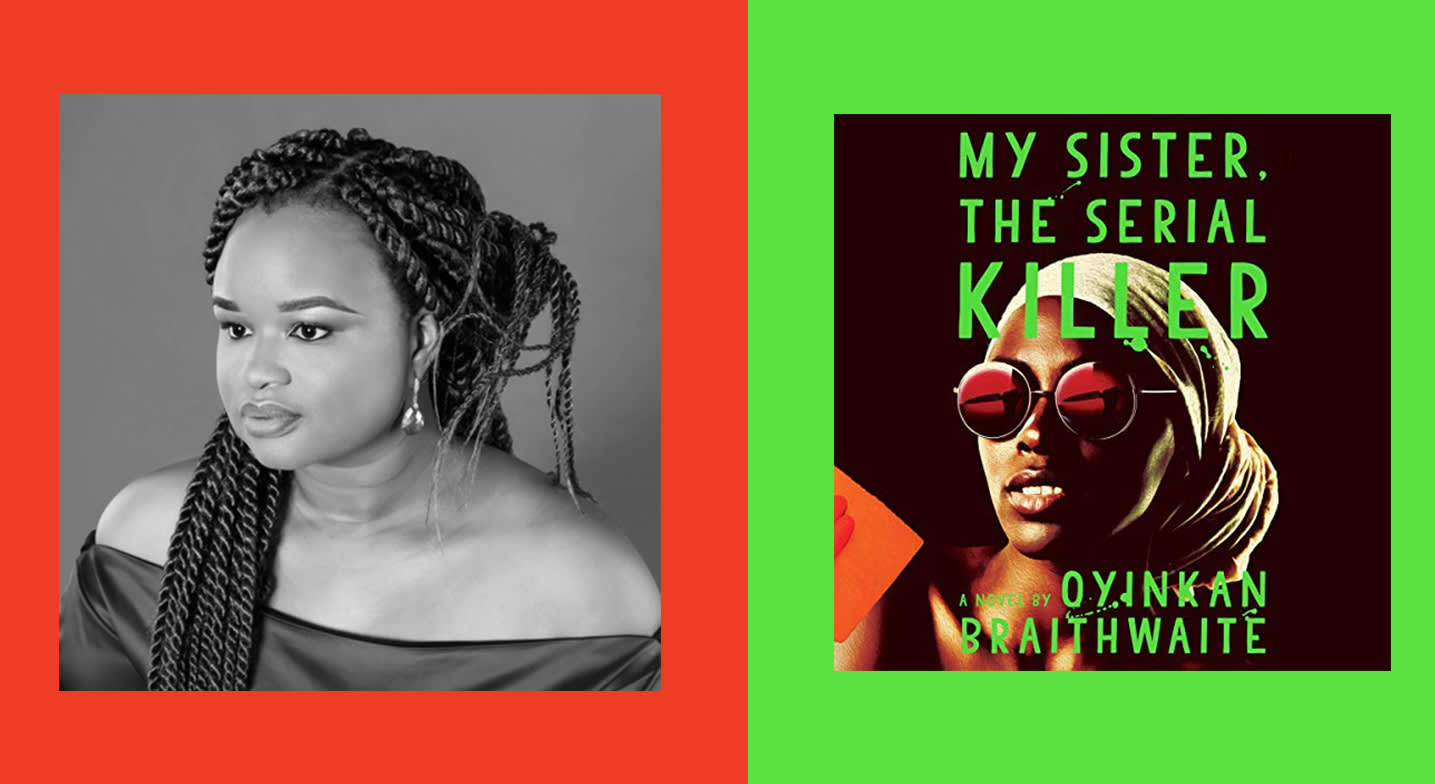

Debut author Oyinkan Braithwaite, a former finalist for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize, who's also known for her spoken word skills, spoke with editor Rachel Smalter Hall about the smartly-paced and sneakily funny thriller. And it quickly became clear that the thought process behind this lyrical and engaging novel meant it would be a treat in audio.

Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

Rachel Smalter Hall: Hi, I'm Rachel Smalter Hall, an Audible editor, and I am thrilled today to have the opportunity to talk to the author of one of my favorite crime novels of the year. She is Oyinkan Braithwaite. We went back and forth on trying to get me to say the correct pronunciation. Could you please say your name as well? Just so our listeners can hear it in your own beautiful voice?

Oyinkan Braithwaite: Okay, so my name is Oyinkan Braithwaite.

RSH: Tell us where you are joining us from today.

OB: I'm joining you from Lagos, Nigeria.

RSH: All right. I am in Newark, New Jersey. So, we are literally in very different parts of the world. Thank you so much for joining me on this call. I'm a huge fan. Yeah. I'm a huge fan of your book My Sister, The Serial Killer. The title really says it all. How did you land on that title for this book?

OB: That genius was not my genius. It was Claire Alexander who is my agent. She named the book. I was actually initially a little bit resistant to the name. Because for the same reasons I think people love it. I love it now too, but at first, I thought it was just so on the nose. Initially I just thought, "I don't know, I don't know." I trust her so much. And she was right.

RSH: What I love about it is your writing is so economical. The title too just says so much about the story. It sets up the family relationship, the crime element, and also the subversive humor that runs through it. To me, it's just the perfect title for this book. That's so interesting to me that you were resistant at first. What did it take for you to come around to being happy with it?

OB: I think I just trusted her. It makes things so much easier for me. So, when people ask me, "Oh, what's your book about?" ... "Oh, what's the book called?" And I tell them the name, at that point, I really don't have to say anything anymore.

RSH: Right.

OB: I'm just like, it's exactly what it says it is.

RSH: Right.

OB: It makes my job easier. It's interesting people's reactions to it. Especially here in Nigeria, people kind of double back a bit. Like, "Wait, hang on a minute. What did she just say?" So, it's fun for that reason as well.

RSH: So, that actually sets up my next question beautifully. For those who are listening that don't know much about the story. Could you just set the scene in the story for them?

OB: Okay. So, it's about two sisters. The older sister is the narrator, and the younger sister has an inconvenient habit of killing her boyfriends. The older sister is supposed to have to deal with this trait of her sister's.

RSH: Tell us, what are the names of the sisters?

OB: Okay, so the older sister is Korede. I know people have been struggling quite a bit with the names. The older sister's name is Korede, and the younger sister, her name is Ayoola.

RSH: Korede, and Ayoola.

I knew there was going to be this contrast because of this theme of beauty. So, the contrast had to be there in terms of how they looked.

OB: Yeah.

RSH: Okay, close enough. So, these sisters, they're such a great literary duo. Can you tell me how you came up with the idea for each of the sisters? Did their dynamic kind of come to you over time, or did it come to you fully formed?

OB: I think Ayoola came to me first. Because for me, the novel, this theme of beauty, was very important to the story I was trying to tell. I knew Ayoola was there, and I knew she was beautiful, and I knew she was the one that was going to be doing XYZ. But the thing I kind of decided that I didn't initially know was about her was her childishness. I sort of see her as being a little bit child-like. That's something that when I happened upon I was like, "Yes, this is her, this is it."

RSH: Yeah.

OB: Once I had her, creating Korede was much easier. I knew there was going to be this contrast because of this theme of beauty. So, the contrast had to be there in terms of how they looked. Because she's the older sister and Ayoola has this child-like quality to her, it was easy to give Korede this protectiveness that in some way binds her. So I think that's kind of how it worked out in my mind.

RSH: Right. Okay. It's interesting to hear you talk about the theme of beauty, which I definitely picked up on in the book. I had a very specific interpretation of the book. Then I passed it along to my co-editor, Abby. She had a completely different interpretation, which fascinated me. So, can you tell us in your words, what this book is about to you?

OB: I've had people ask questions, and people kind of tell me what they think. Now I feel that my initial thoughts about it might even have changed also, because of the conversations I've had with other people. I know that writing it at first, I thought about beauty. I thought about how facetious society is. How facetious social media is. I thought about how we present ourselves to the world, and who and what we actually are. So, the family dynamic and family relationship actually weren't something I thought about. It was something that happened on its own. Just how shallow I figured people could be was something that I wanted to explore. Sort of how we respond to things when we're pushed or cornered in some way.

RSH: Sure. That makes a lot of sense. I think there's a way that you can read Ayoola as she's obsessed with the social media. For me, I was surprised that as the story went on, I did find kind of a depth to her. I'll just tell you. How I understood the story was a commentary on how these sisters are reacting to the men in their lives who are oppressive. Also, a rejection of the pressure put on young women to marry. I don't know if that was just me projecting my interpretation onto it. How do you see those gender dynamics play out?

OB: The gender dynamics. For Ayoola in particular, I found her character freeing, because I saw she's not affected by any of it. She's not affected. I mean, she is to some extent, but I also saw she doesn't do things out of revenge, necessarily. She doesn't do things because she feels like she's been oppressed or anything like that. She does it because she can. I think there's something to be said for that. She does it fairly because she can, and it suits her to do a particular thing at a particular time. She doesn't think too deeply about it.

OB: I think for women, generally, a lot of the times we are responding to things that have been done to us, or are being done to us. Ayoola isn't do that. Korede on the other hand, is responding a lot to things that have been done to her. Things that are being done to her, and she's been damaged by certain things. I think she does take the power back herself, in a way, towards the end. Where she decides, you know what, it's not about these different guys, it's about me and my sister and we're going to stick together.

OB: By then it was too late, because the book was already in the hands of the publishers, but I actually kind of wondered what would have happened had I made it their mother who was the negative influence in their life, as opposed to the father. I thought, how would that then affect how people saw the book? I don't necessarily see Ayoola as a victim, even though everyone could argue that she is. I don't think she thinks she's a victim.

RSH: Right. I completely agree with that. She seems quite content and happy in her life. Considering all the circumstances. So I want to talk about Korede a little bit. She manages her emotions by obsessively cleaning. She's very fastidious. Do you have it in her mind that she has something like obsessive compulsive disorder, when you were writing?

OB: Yeah, I think I did to some extent, but not too heavily. I think I did read up a little bit on the subject but, yes, I think it is her coping mechanism anyway. It's the only way she knows how to cope with certain things. To make a life that's not making any sense tidy, and clean.

RSH: Right, right. I'm curious, in Nigeria, is mental health discussed very openly?

OB: I think it's starting to be more, and more. I know a few writers that's their primary focus. I think people are becoming more outspoken about it. There's a Nigerian rapper recently who did an album that focused quite a bit on mental health. It's definitely something that's being discussed more and more. I think in the past there was definitely this shameful thing about it. We're this society, where you kind of keep things within the family, and not expose your family's secrets to the world, or anything like that.

I'm definitely not any type of expert on the subject. I do think things are getting better now.

Because Korede has always been so protective, Ayoola plays the role of a child. Because that's the role that they left for her to play.

RSH: Right, okay. I want to talk a little bit about this close family unit. There's definitely this loyalty, of course, that runs through between the sisters. Is it more sisterhood, or family, or what is that bond that for you was informing the way you wrote the story?

OB: I think it was for me, I'm the eldest of four. I think that we kind of all know the role. When I see my family, we all have our roles that we play. Half the time, we're complaining about these roles. Including my parents. They're all convinced that they've been pigeonholed into this position where they play a certain part, or they do a certain thing. But, they can't escape it. It's like that's just the way it is. I've had conversations with my mom where I'm like, "You know, you can just stop. If doing this particular thing upsets you so much, just stop it." She said that she will, but she can't.

OB: First, she's convinced that if no one else does it, she will. Deep down, that's the way she wants things to be. She wants to do them. I think that family has that weird thing where ... It's unit, in some ways, everybody has to play their part in order for the unit to work. Again, sometimes you play a part that you're not comfortable playing, but you feel like you don't have a choice.

People are focused a lot on Korede, but the same thing with Ayoola. Because Korede has always been so protective, Ayoola plays the role of a child. Because that's the role that they left for her to play.

RSH: Right. And I think it's so interesting that she does have this talent as a designer. It's almost like she's been stunted in a way that she hasn't had an opportunity to really let her personality flourish in a way that would give her more depth or dimension. I don't know, but I totally see that.

I don't mean to put you on the spot, but I'm curious, can you give us an example of something that your mom does where you're like, "No mom, you really don't have to do that anymore."?

OB: There's a girl right after me. We're three girls and one boy. The girl and I were fairly close in age because she's three younger than I am. The other day, my dad was having his 60th birthday. She and my mom, they're both the more fastidious people in the house. They were planning everything to the T. They planned the venue, the catering, the decorations, everything. I was given the job of doing the invitations, designing the invitations and all of that. So I have my one job. They had taken everything on. At some point I realized that my sister is angry with me. She's like, "I did everything."

Funny, my sister was angry with me, my mom was angry with dad, because my dad just basically shows up at this fabulous birthday party, and he showed up late. You've not done anything towards this, you've not done anything. My sister's like, "I went to this, I did this. And what were you doing?" Nobody asked you. Even the birthday boy is just chilling. She was just really annoyed. I understood, because yeah, she did take a lot on her plate, and my mom did take a lot on her plate. I'm just wired differently. To me it's just not that important.

It's that sort of thing. She made the choice that she made, but she wasn't happy with them. If you don't like to do something, just don't do it. Often we feel like we don't have a choice.

RSH: Right, and families just kind of fall into this rhythm. These patterns that are so deeply embedded. You can see that between Korede and Ayoola for sure. They just have this dynamic. That's just how they are. Thank you for sharing that story, I love that.

RSH: So, while we're talking about the family, I would love to pick your brain a little bit about the class commentary that's in this book. I want to know a little bit more about Korede's family and why they choose to stay in their home, even when it becomes financially difficult. They have what you've called a house girl. Talk to me a little bit about that decision they make to stay in that home.

OB: The decision to stay in their home because at the end of the day ... in Nigeria depending on what your income is like, where you get to a certain stage in life where your bank account is looking friendly. We build houses a lot in Nigeria, in Lagos. Well, I think it's probably in Nigeria, generally. We build houses a lot. We rent a lot as well. But most people try to aim in building a house. Once you build your home, you're not paying a landlord yearly rent, or monthly rent, or whatever it is. You've hopefully got the home of your dreams. A lot people do ... we have a lot of estates in Nigeria where people will buy land in the estate, then eventually they will come and build their home.

OB: So, it starts on a case for Korede and Ayoola. The thing is, once their dad passes and they lose that financial security, the home is still theirs. They're still not paying rent on the home. In this particular story, their dad cut a lot of corners when he was building the home. So, nobody would even buy it, if they wanted to sell it. So, they actually are stuck there, they don't have a choice. So, it's just a custom in maintaining the home they have to manage.

OB: I guess with class, there's a major class divide in Nigeria. I want to be careful here in case any Nigerians come for me. There's a major class divide in Nigeria. There's this sense of we still have this culture where you don't marry, you're not encouraged to marry below a certain class. Some people are still considered to be social climbers. We still have that sort of society. Regarding house girls, again, that's a very common thing. House girls, drivers. In England, before you get a chauffeur, you have to be really wealthy. Then chauffeurs are well paid, and it's a job that a lot of people would be happy to do. In Nigeria, it's not quite like that. Labor is cheap here. So, drivers, house girls, nannies, are paid fairly poorly.

Because I love the way poetry sounds and the way poetry flows, it's affected the way that I write my novels.

OB: I think nowadays, a lot of them are treated quite well, but I know some people treat their staff fairly poorly. It's a common thing here. You don't have to be ridiculously wealthy to have a house girl, or to have a driver. I think once you're in the middle class, even maybe lower middle, you already have a house girl to help out.

RSH: I found it was interesting that the family continued to have a house girl, even when they became economically stretched. It sounds like that might be-

OB: It's not as expensive as you would think. You would be able to afford one. And a house of that size, they would need the help.

RSH: Right. I'm going to shift a little bit to your background. You're a slam poet, you're a short story writer, and an editor. How did you find your way to writing a crime novel?

OB: I've always wanted to be a novelist. That's kind of where I've been heading the whole time. I didn't think I was writing a crime novel, necessarily. I didn't think too much about genre when I was writing it. I had another interview where I mentioned when I see my book come up somewhere, I check the genre to see what genre they've put it under. I'm like, "Okay, I see it, I see it." I'm actually curious to see what other people, what genre they think it's in. To me, I wasn't sure when it was finished, what to package it as.

RSH: Oh, okay, that makes sense.

OB: These days, I'm leaning to a psychological thriller end of things.

RSH: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

OB: Did I finish answering that question? I'm not even sure.

RSH: I think you did. I was just wondering how you found your way to writing a crime novel. I was thinking that it's interesting if this novel were not titled, "My Sister, The Serial Killer", I wonder if it would be so obvious that it is a crime novel. In your mind, is it a crime novel? What is it to you?

OB: It's funny. It has to be a crime novel because there are crimes being committed. My dad finally read it, finally finished it. He was so worried. He doesn't want to have to do with all this blood and gore. It's really not that. It's not a bloody story. It's not that deep. My mom still refuses to read it. She doesn't want to have nightmares. I'm like, "It's not that serious." So, even though there are crimes being committed, yes, they are central to the story, but they're not what the story is about necessarily. So it's weird.

RSH: Yeah. I love it though. I think it gives it a little extra edge that I really enjoyed as a reader and a listener. So, with your background as a slam poet. Of course, you've won awards for your slam poetry. You've been short-listed as a top 10 spoken word artist. Can you talk to me a little bit about the audio form? What does it mean to you to hear the spoken word out loud?

OB: I love hearing the spoken word. The thing about poetry in general, I have to say, I'm not a great spoken word artist. I'm better at writing poetry than I am at performing it. It's not my greatest skill.

I appreciate the rhythm and the sound of someone performing poetry. Also, the thing about poetry that I think novels novels do have, but in a watered-down manner is that when somebody drops a poem for you, whether it's rare or the written word, they can speak your experience even though they died centuries before. Or they're from a completely different culture. Or a completely different gender. They can be you in that moment. They can be what you've experienced, and what you've felt. It's almost to that veil ... I say it's watered down in novels because novels get bogged down in plot. So even though you can still in moments, "I felt this way," generally the story is not your own. Poetry is generally about emotion. I think it can connect people in a way that nothing else does. Almost music that does the same thing in song.

Because I love the way poetry sounds and the way poetry flows, it's affected the way that I write my novels. Even the way I pick names. I pick names based on sound sometimes. Korede and Ayoola: I made that choice. It was a sound choice, because the sound of Ayoola is very soft, and it's lyrical. I just thought it was a soft sounding name. It was a pretty sounding name. Whereas Korede is harder. It's got the D and the K, and it's a more broken name in my mind. This is the way I think about stuff. I do think about it even in writing prose.

RSH: I love that so much. It makes this even such a richer experience in audio to hear those sounds that you have spent so much time thinking about. To hear those brought to life by the actress who reads the audio version. Have you listened to any samples of your book in audio yet, or do you plan to?

OB: I've heard samples, but not from the people that were actually chosen in the end. I think that was UK anyway, it wasn't the U.S. I have heard the sound of the narrator talking on something completely different. I'm looking forward to it.

RSH: So in the U.S. I'm afraid I'm not going to say her name correctly, but she's an American Nigerian actress, Adepero Oduye.

OB: Yes.

RSH: So, she's from Brooklyn. To me, it's so beautiful to hear that rhythm of the story that you've told. The rhythm of the language brought to life by this Nigerian American actress. For you, do you think it's important to the authenticity to have a Nigerian American narrator?

OB: Yeah, I do. Probably any Nigerian language is probably one in which people are not exposed to. The non-Nigerians are not exposed to. I think it's a lot to ask of someone to say the names and the places, and the phrases without just coming off ... you know the Hollywood movies where ... I don't know if you guys know, but over here, we're always cringing when we hear the actors do a Nigerian accent. Because we're like, "No, that's not what we sound like."

RSH: Right.

OB: So, I think it was really important to me that it not sound weird. I would even prefer they stayed in there ... she's Nigerian American, so she will have an American accent to some extent. I was like, She should be true to how she sounds. As opposed to forcing it. The truth is, Nigeria at the end of the day, we've been influenced by so many different ... Nigerians are everywhere. When we come back, you've got people who have Nigerian British accents. You've got people that have Nigerian American accents. You have people who have full on British accents. You have people who speak Pidgin only. So we're kind of a melting pot of different accents and different languages. Because in Nigeria, we don't just speak one language anyway.

It was important that it not come off and make us cringe over here.

RSH: Right. There's something about that authenticity of her speaking in her own version of a Nigerian accent that gives that authenticity to the story a little bit more.

OB: Yeah.

RSH: What is the language of origin for the names?

OB: They're Yoruba, then some characters are Yoruba and some are Igbo, some are Hausa in the book. So they're actually from different tribes. But, that's just the way Lagos is. I didn't even really draw attention to it like that. You wouldn't know unless you were here, based on just the names, that oh, they're from different places.

RSH: Has the book been out in Nigeria already, or is it coming out simultaneously across the world?

OB: It's coming out in the U.S. in November. It's coming out in Nigeria in December, and it's not in the UK in January.

RSH: Wow, that's so exciting. Well, I hope everything goes brilliantly with all of the upcoming release dates. I know we've been really excited about it here. I've been hearing really great buzz from people in the business and other readers and listeners who are really excited to get their hands on this. I'll leave you with one last question. How do you hope listeners and readers will respond to Ayoola and Korede?

OB: I want them to enjoy it. Because I enjoyed writing it, and I think that is the most important thing. So even if they left with no idea of what scenes were in the novel but they laughed sometimes, or they thought, "This is interesting." I think that would satisfy me. I think just the fact that people have read it sometimes and they said that they read it in one sitting. Or they couldn't put it down. I love it when I have that experience where I'm trying to stretch a book because I don't want it to end. Because I think when it ends, what am I going to do with my life? If I could do that for someone else, I would be so grateful.

RSH: Well, thank you so much. I think you are in luck, because I think that's definitely going to happen. I know that's already happened for us here with our advanced copies. Best of luck with everything. We wish you all the happiness and success with this novel.

OB: Thank you, Rachel.