Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

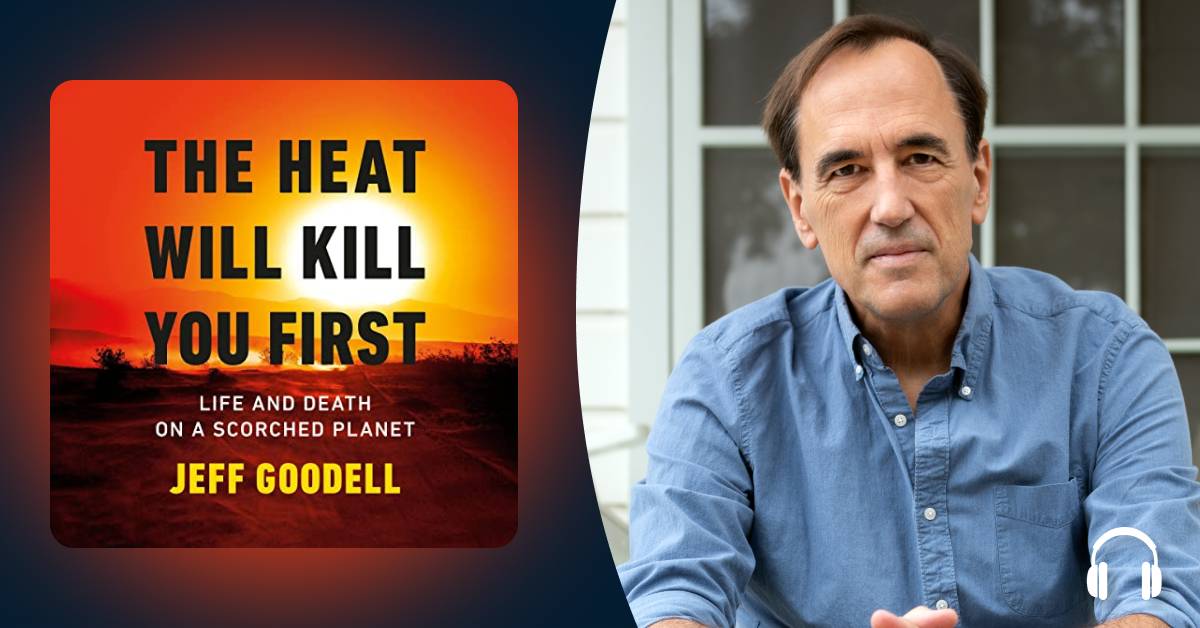

Phoebe Neidl: Hello, listeners. I'm Phoebe, an editor here at Audible. Today I have the pleasure of speaking with Jeff Goodell, an award-winning journalist and the author of numerous acclaimed books about climate change, including 2017's The Water Will Come and the 2019 Audible Original The Big Melt. Jeff is also a longtime contributor to Rolling Stone magazine, and is currently an Atlantic Council Fellow. Today we'll be talking about his new book, The Heat Will Kill You First: Life and Death on a Scorched Planet. Welcome, Jeff.

Jeff Goodell: Hi, Phoebe. Good to be here.

PN: Just so listeners know, Jeff and I go back. We used to work together at Rolling Stone. I was lucky enough to be one of his editors there, so I am extra thrilled to have the chance to catch up with him today.

So, one fact I think a lot of people probably aren't aware of with heat exposure is that it actually kills more people than all other natural disasters combined. Whereas things like hurricanes and floods tend to get the bigger headlines, heat is sort of this silent killer, right? Can you talk a little bit about why heat deaths fly under the radar?

JG: First of all, because it's very hard to diagnose, right? A paramedic doesn't walk into an apartment and find someone who has passed away and say, "Oh, they died of heat." They say, "Oh, they died of a heart attack." Or of kidney failure. Or of something like that. So, heat is very difficult to actually diagnose as a reason for death. And some of the stories in my book talk about that. And it's also true that we're not used to thinking about that. We're not used to counting heat deaths and attributing them to climate change. To the degree that they're counted at all, it's just, "Oh, it's a hot day. You know, grandma had a weak heart, and we're sorry she passed away, but you know, there she goes."

And what's happening now is we're starting to understand the correlation between people's health and between rising temperatures. We're starting to understand much better the difference between the risks of dry heat versus the risks of wet heat. I mean, it's one of the fundamental discoveries about reporting this book. And one of the reasons I wrote this book was because I realized after I've written about climate change for basically 20 years, and despite the fact that it's been called global warming and everybody knows it's about the planet heating up, there's been very little research and reporting and understanding of what the real impacts of heat are on the human body, and, in fact, what heat even is. So, all of that is wrapped up in this question of why we don't understand heat mortality as well as we should and as well as we're learning to.

PN: Yeah, it's so true. I feel like this gets right at the heart of climate change in a lot of ways. It seems almost so obvious, but I don't think anybody has looked at [heat] as directly as you have, just as far as how it's going to affect all living things—plants, humans, animals. I learned so much from this book. And to the point of [how] it's going to affect all living things, another theme in the book is that the risks aren't the same for everybody, right? Can you talk a little bit about how social inequality puts some people at greater risks from heat than others?

JG: Yeah, this is a great question, and a really important question. All of us are sensitive to changes in heat. Not only all people, but all living things. One of the things I talk about in the book is this idea of the “Goldilocks niche”—that everything on Earth evolved in this certain temperature range. In fact, when astrophysicists look for life on other planets, what they look for is this Goldilocks niche, which for all intents and purposes is where water is liquid, where it's not frozen or vaporized.

So, this question of sensitivity to heat is important to everything. But, of course, in the real world that we all live in, we have different kinds of adaptations to that heat. I, for example, am talking to you from Austin, Texas, right now. It's a spring day. It's June. The temperature today is forecast to be 103 degrees and humid. It is brutal outside. But I'm sitting in my house, and I have air conditioning on. And I have an insulated house, and I look out my window and I think, "Oh, it's hot out there." But I'm okay. I drive down the street, and I go to East Austin, and I see a lot of people who are homeless, who are out on the street, who are red-faced and suffering from this, who are not in the best health. That makes them even more vulnerable to heat.

I know from my reporting that there are a lot of people who don't have a lot of money, who live in apartments that are not very well insulated. They run the air conditioner as much as they can, but it's expensive because air conditioners are not economical, the houses or the apartments aren't well insulated. So, they put them on an hour or two a day. And they're making a calculation of, "Oh, okay, it's 104 out. You know, I'll spend $25 today," or whatever the number is, and run the air conditioner for a couple of hours. So basically, the big-picture story is that privilege and money buys you comfort and buys you insulation from the risk of heat. And that is the fundamental problem of this sort of injustice of climate change, and the fundamental problem of the injustice of extreme heat.

PN: And then compounding that, right, is that there just isn't the sort of public education about the risks of heat that there are for some other things. It's interesting, you talk about an effort underway to name heat waves, the way we name hurricanes. That maybe this would help people understand that this is a real health hazard going on.

JG: I mean, one of the difficult things about that, about becoming aware of the risks—and you're right, there isn't very good communication about it. And this goes to things like the jobs that you and I do in the media, which is like, “How do you communicate about heat?” I mean, you watch TV or in newspapers on a hot day, and images are often of kids playing in sprinklers. Or people at the beach. And you think, "Oh, so it's hot. It's no big deal, so we'll turn the sprinklers on."

One of the difficulties about heat and why it's so dangerous is because it's invisible, you know? It's very hard to visualize what a heat wave is. It’s not hard to visualize what a hurricane is. It's not hard to visualize what a drought is. It's not hard to visualize what a melting glacier is. But it's really hard to visualize a heat wave.

"Basically, the big-picture story is that privilege and money buys you comfort and buys you insulation from the risk of heat. And that is the fundamental problem of this sort of injustice of climate change, and the fundamental problem of the injustice of extreme heat."

PN: This book is the result of years of reporting. And one of the things that makes it so engaging to read is all of the travel and all the different people that you talk to. I mean, you reported from Antarctica, Oregon, India, you're at the Great Barrier Reef, you're skiing through the Arctic. You're all over the place. And you talked to so many people. And what's so powerful, it's not just scientists and academics, but it's real-world, average people who are on the front lines of bearing the brunt of climate change and trying to document climate change. And you tell their stories. So, I'm curious, what were some of the most powerful moments you had in the course of traveling for and reporting this book?

JG: Oh, there were so many. And you're right, I really wanted this book to feel like you were with me out in the world. I mean, I think about going around Phoenix on a 117-degree day with these two guys who were working with a Phoenix church, who were going out to check on people in the heat, going to people's apartments, going to homeless people. I remember walking in a park in Phoenix, into a bathroom, which they happened to know was a hangout for homeless people. And there was a woman kind of sprawled out there. It was 117 degrees that day. I don't know how hot it was in that bathroom, but it was really hot. And you know, they’re talking to her, bringing her water, trying to convince her to come into a cooling center, her resisting that. People like that, where you see sort of literally death in their face, from this heat. And the difficulty of saving people from that.

Going to Antarctica was a whole different kind of experience. Because you would think, "Oh, what does heat have to do with Antarctica?" Well, it has a lot to do with Antarctica, because what's important about heat is not just that “Wow, the temperature's really hot and it's really dangerous.” But also how small changes in temperature can have such a huge impact. I was on a ship that was right at the face of Thwaites Glacier, which is this big glacier that's one of the most at-risk glaciers for the whole West Antarctic ice sheet. And long story short, the scientists determined on this trip that this glacier is radically destabilized and if it falls apart, it has huge implications for virtually every coastal city in the world. But it's a temperature change of less than one degree in the water that is destabilizing this whole ecosystem.

And then, I also think, just the last example, is the reporting I did about changes in disease outbreaks. Heat changes where animals want to be, just as it changes where you want to be and where I want to be. If it's a hot day, I want to go to a cool place. Same thing with animals. Same thing especially with things like birds and mosquitoes. And especially mosquitoes that carry various diseases. They're vectors for diseases. And wandering around Houston with a mosquito catcher, and him talking to me about how the patterns of mosquitoes have changed in South Texas over the past 10 years just because of changes of a few degrees in temperature. It really gave me this visceral feel that every creature on this planet is sort of moving and trying to find a comfortable space. And the implications of that are enormous.

PN: Yeah, I actually have a question about that. This strikes me as an area where it might be harder to predict exactly what impact rising temperatures are going to have. Because just one keynote species disappearing or changing its migration pattern can have a big domino effect, right? So, my question is, do the scientists you've spoken to worry that there are domino effects with extreme heat we haven't even thought of yet? Or do they feel like they have a pretty good handle on what's coming down the pike?

JG: No, they do not have a good handle on what's coming down the pike. I mean, that's one of the forefronts of climate science right now, is trying to understand these cascading effects of one species moving or changing or one species dying out, and what that means for all the other species that depend on it. One kind of classic example of this is in the Rockies, with pine bark beetles. As it gets warmer, these pine bark beetles are able to move into new areas. They're devastating little beetles that destroy the pine forest in the Rockies. More heat makes the trees weaker because they're more stressed, because they need more water. They don't have it. That makes them more vulnerable to the pine bark beetles. So, the trees get attacked by the pine bark beetles. They're dryer, they're weaker. And then they're also more vulnerable to forest fires, and so you begin to get more [fires], as we obviously have just seen with what's been going on in Canada with the wildfire smoke. You get these cascading effects. You could argue that the changes in pine bark beetle habitats impact the lungs of people in New York City or in Los Angeles.

And so these cascading effects of what it means for these small shifts, how they amplify, is a really complicated question when it comes to these changes in the ecosystem that I write about in this book. I think it's the hardest thing not just with heat, but with climate change in general, to get your mind around, is that we're not talking about just the loss of the species. Or we're not talking about just putting more air conditioning in your house or something like that. There's all of these cascading effects, good and bad, that we have just not even begun to understand.

PN: So, climate change is a pretty depressing topic, obviously. But one of the reasons I've always loved your writing, while you don't sugarcoat at all how dire the outcomes can be, there is a sort of awe of nature and science that comes across in your work that I find kind of strangely uplifting. So, is this something that you sort of consciously do when you're writing to mitigate what a hard, scary subject this is? And is thinking about the emotional impact something you take into consideration as a climate writer?

JG: You know, that's a great question. And a difficult question. I'm often asked, because I've been writing about climate change for 20 years, "Why are you not just an alcoholic who just is so depressed and just chugging bourbon every evening? And how can you keep writing about this?" But I think there's two things for me. One is that, I'm a journalist. And as a journalist, I'm attracted to good stories. And I think climate change is the great story of our time. In every dimension.

Whether it's talking about how we as humans are going to deal with this politically. Whether it's about what mosquitoes are going to do and how they're going to move. Whether it's about how glaciers are going to react. Whether it's about entrepreneurs and new businesses. Whether it's about urban design and how cities are going to be built. I think watching this play out, just as a journalist, forgetting good, bad, whatever, is just completely fascinating. I think it's just amazing. Every time I go out, I learn something new. I find new, inspiring, interesting people. You have really creative, inspired people, politically, economically, technologists, entrepreneurs, activists, whatever, fighting really hard for a better world. And to me, I find that really inspiring.

I also think that there's a real opportunity here to build a better world. I know that there's going to be a lot of loss. And I'm very sad about that. I have three kids, and I think about the world they're going to inherit. And part of my interest in this is trying to shape the world they're going to live in. Like I said, I live here in Texas, and any time I go out for a drive, I drive by these strip malls and stuff, and I think, you know, there are better ways to live than the way we're doing it. Maybe climate change is going to be the thing that inspires us to think differently about how we build cities. It's going to inspire us to think differently about how we think about nature.

It's tragic and sad that we're going to lose so much, and we are going to lose so much, whether it's your favorite beach, or your favorite tree, or people you love. But on the other hand, these moments of change are opportunities to do better. And I think that we can see that in the climate crisis already, is that it's inspiring us to think differently about everything. And as a writer, I just find that completely fascinating, and it's what I try to capture in my work. Both the drama and the tragedy of what's happening, and the hope and the optimism of what can come out of it.

PN: Yeah, I think you use Paris as a really interesting example of just how challenging making these changes can be, right? I'd love to hear you talk about just some of the challenges to making these changes to infrastructure. In Paris, you have those famous, beautiful zinc rooftops everywhere. But at the same time, they trap heat, and they're just boiling people in these romantic, garret apartments that we all sort of romanticize. But good luck trying to change all of the rooftops of Paris, this beloved, most-beautiful city. So, yeah, I'd love to hear you talk a little bit about some of the challenges of getting the world to change the infrastructure for heat.

JG: Yeah, there's many classic ways of framing this challenge of changing infrastructure. But that's certainly one that I found very compelling, because I love Paris. Virtually everyone agrees that Paris is one of the most beautiful cities in the world. And it was these 18th-century buildings that basically define downtown Paris that have these tin roofs on them. And those tin roofs were seen as a great innovation at the time. And we've come to think of them as very beautiful and very defining of Paris and the Enlightenment Age that Paris represents. And yet, those roofs, now, are like convection ovens. They absorb the heat, and to live underneath them is to live in a death trap. And so there's this great fight going on right now between people who love Paris and say, "We can't change these roofs because these roofs are what define Paris." And then you have people who say, "Well, Paris has to move to the 21st century, and has to think differently about what it is." And those 18th-century roofs that define Paris for us now, we have to remember that the architects who built Paris in the 18th century basically bulldozed the city and built those. And the idea that you would bulldoze the city now and rebuild it in some new way is just unthinkable.

So, you have this stalemate going on there. And Paris is doing a lot of great things right now. They're banning automobiles from downtown. I write about them trying to plant and reimagine the Champs-Élysées, and plant a whole bunch of new trees there, and redefine these boulevards and green the city. So, there's a lot of things that they can do to bring the city into the climate age. But it's emblematic of the big infrastructure changes that we have to think about. You know, how do we build buildings? How do we think about air conditioning? How do we think about comfort? What is comfort for us? How much are we willing to sacrifice? That's the difficult thing and the fascinating thing.

"Life on Earth is a finely calibrated machine, one that has been built by evolution to work very well within its design parameters. Heat breaks that machine in a fundamental way, disrupting how cells function, how proteins unfold, how molecules move."

PN: So, one of the things that's definitely going to stay with me the most, I think, from this book, is just the description, the unbelievable description you give of what literally is happening to the body when it's under heat duress. There's a quote I love that sort of talks about this. You write, "Life on Earth is a finely calibrated machine, one that has been built by evolution to work very well within its design parameters. Heat breaks that machine in a fundamental way, disrupting how cells function, how proteins unfold, how molecules move." And obviously, you can't go into the whole, long description of what's happening in the body, but it makes me think differently about how I conduct myself in high heat. And I find myself now, like, lecturing other people about it [laughs]. So, as just sort of almost a practical matter, are there two or three things, like top key things you would tell people to do in extreme heat in order to keep themselves safe? Because you can be healthy and well-hydrated, and it's still a great risk to you, which I learned in this book.

JG: Water is really important. And if you're out on a hot day and you're on a hike—I write about a family that died on a hike in my book—and you don't have enough water, you will sweat out all the water that you have, basically. And then your body will have no mechanism to cool down. And so that gets very dangerous very quickly. However, it is also true that water can only dissipate so much heat. So, if it's really hot, or you're exercising really hard, or your heart isn't working very well for whatever reasons, it doesn't matter how much water you have, your body will still not be able to dissipate the heat. Your heart will pump really, really hard. You won't be able to cool it off, and you will die. Or have heat stroke. So, this myth that drinking water will save you, I think, is really, really important to sort of understand.

The other thing is this difference between dry heat and wet heat. So dry heat is in certain ways much less dangerous because your body can continue to sweat. And as that sweat evaporates, it cools you off. Everybody knows this, but 110 degrees in the desert is different than 110 degrees in New Orleans, right? When it's more humid, your sweat doesn't evaporate because there's already so much water in the air, and so your body doesn't cool off.

And the other is the vulnerability of different people. I mean, nobody's immune, ultimately, to the impacts of heat. But it's basically true that the better health you are in, the better you're able to deal with heat. A 22-year-old athlete will be able to thrive in higher temperatures for a longer time than an 80-year-old who has a weak heart. Because the first thing your body does when it gets hot is it pumps blood around to get towards the surface of your skin so that it can dissipate the heat. And so it puts a lot of strain on your heart.

And then the last thing I'll say about what to do is everyone is more or less the same vulnerability, given their health. So, it's not like if you grew up in Mexico or the Philippines or something, you're less vulnerable to heat than if you grew up in Alaska. What's very different is people who grew up or live in hot climates understand how to deal with heat. And I learned that for myself here in Texas. When I moved to Texas a few years ago and we had some work being done on our house, I noticed these workers were taking breaks all the time. They're sitting in the shade all the time, and like every 20 minutes, they're stopping and going and sitting down. I finally started talking to them, and they're like, "Yeah, this is how you have to work in these kinds of conditions. You have to understand that you work differently." So, the whole idea of a siesta, you know? It came out of working in hot climates. And it's something that humans have known for a long time. But we've forgotten partly because of air conditioning and partly because we haven't had to deal with extreme heat as much as we are now learning that we have to do.

PN: So, I want to talk about the audio performance of this. L.J. Ganser narrates this book. He's a veteran narrator who's won lots of awards, deservedly so, and he does a wonderful job. You had actually narrated your Audible Original, The Big Melt. So, I'm curious, did you consider maybe narrating this one at all? And if not, what were you looking for in a narrator?

JG: I didn't consider narrating this at all because my experience narrating The Big Melt gave me incredible respect for the people who have the ability to narrate these books and to give every sentence the kind of weight and drama that it deserves. I work very hard in writing this book to tell a story. I'm not trying to write a PhD thesis here. I'm not trying to write an argument. I'm trying to tell a story that is full of people, of travel, of different places, of people that I meet. And I really feel like it's really important that the narration reflect that. That the narrator understands that, you know, that this is a story. This is not Huckleberry Finn, okay, but it's more Huckleberry Finn than it is a PhD thesis. I want the narrator to really capture that. And I think that he's done an excellent job here of doing that.

And the other thing is that I think for a book like this, the voice, the narrator, has to be full of a kind of life and kind of capture the fascination and the complexity and the, you know, strange thing to say, the sort of wonder of what I'm writing about. This is not a doomsday book, even though it is about how heat can kill you, it is not at all a doomsday book. I've described it as sort of a beach read for the climate age. It's really important that the narrator understand that and capture that. And not make it feel like some sort of apocalyptic sermon.

PN: Absolutely. Exactly. I think he really nailed the right tone for this. So, my final question is, if you were going to leave listeners with one thing you really want them to understand about the extreme heat we anticipate from climate change, what would it be?

JG: One of the really important things to really grasp when we're thinking about the climate crisis in general and about extreme heat and the risks of extreme heat is, first of all, why this is happening. It's very clear that this is happening because we are continuing to burn fossil fuels, and we're loading the air with more and more CO2. And that CO2 traps heat. And that's what's ultimately driving this. But it's also really, really important to understand that there's a serious and inspiring effort right now to move off of fossil fuels. And even the hardcore fossil fuel people know that the fossil fuel era is coming to an end. And the acceleration of investment in clean energy here in Texas and in many red states, actually, is really amazing.

But the temperature of the atmosphere is not going to go back to normal as soon as we get off of fossil fuels. That CO2 stays in the atmosphere for thousands of years. It's not like smog or air pollution. We used to have smoggy cities. I grew up in California. I remember seeing the yellow mountains in the Bay Area. And then catalytic converters were put on cars, and we really did a great job of cleaning up air pollution. And within a decade, you could see those mountains that I could never see as a kid, very clear. The same thing is not going to happen with climate change. The CO2 that we're putting up there is going to stay there for thousands of years. So, our temperatures are not going to go down until those CO2 levels go down, which are going to take thousands of years.

And so we're going to be living on this hotter planet for as long as you and I and our generations can imagine. And the implications of that are really enormous. And really important to grasp. And it makes the urgency of getting off fossil fuels all the more important because every molecule of CO2 we put up there, we're going to have to live with. And our kids and grandchildren are going to have to live with. And the temperature is going to stay high. If we went to zero emissions tomorrow, if everybody in the world changed their car for a skateboard, and every airplane was grounded, and we went just magically to zero emissions, the temperatures would stay exactly the same as they are today. They would not cool off. And that, I think, is a fundamental fact about our world and about what we face that is really important to grasp.

The other really important thing, I think, to leave everyone with in thinking about extreme heat in particular is extreme heat is, as we've talked about, the biggest risk to human life and to the life of every living thing on the planet that is manifested by climate change. But it's also the one that is easiest to save ourselves from, in a way, right? Nobody should die of extreme heat. All we need to do is get better at communicating about it. Get better at getting people into air conditioning or cooler buildings. Better at building shade structures, better at planting trees. There's ways of dealing with heat. There's ways of, instead of 15,000 people dying in France in a heat wave in 2003, you know, none of those people should have died. There are ways of dealing with this.

And some of it is as simple as calling up your aunt and your grandmother and your grandfather and anybody you know when it's hot and saying, "Are you okay? Do you need help? This is a risky situation, Mom. You need to make sure you have air conditioning or you have access to a cool place." And so in the sense that small action can save a lot of lives when it comes to heat and heat waves is really important to understand. And so to me that's really actionable. And you know, we can save thousands and thousands of lives just by being a little bit smarter. It doesn't require rebuilding entire cities. I mean, we're going to have to do that in the long run. But in the short run, this summer, we can save a lot of people's lives just by thinking differently and paying attention and communicating about it.

PN: That's a great point. I'm really glad you brought that up. That's good to keep in mind. Well, Jeff, thank you so much for being here. It has been an education, as always. I'm excited for listeners to dive into this and to travel around the world with you and learn about extreme heat.

And listeners, you can get The Heat Will Kill You First: Life and Death on a Scorched Planet by Jeff Goodell now on Audible.com