Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

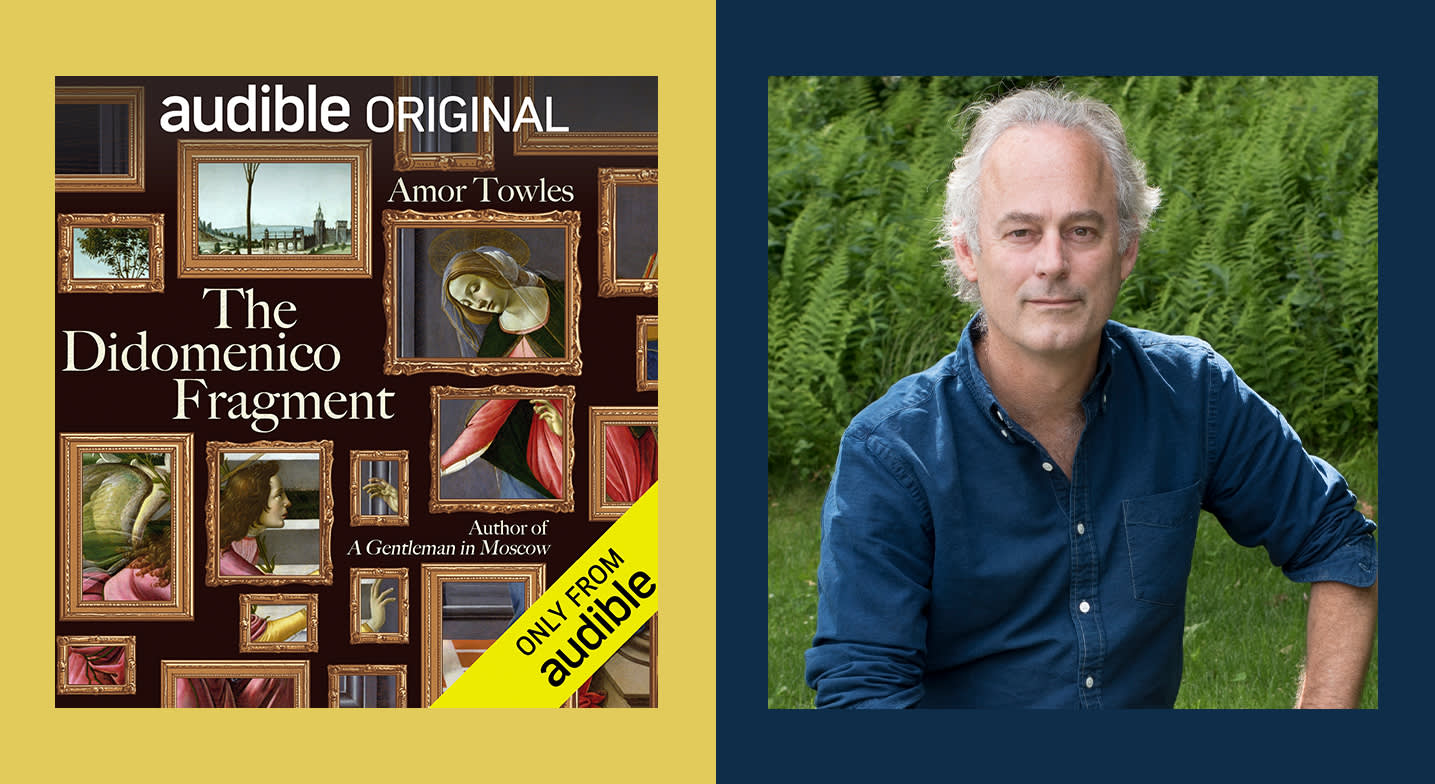

Emily Cox: Hi, this is Emily Cox. I'm an editor here at Audible. Today I'm talking with best-selling author Amor Towles. I've been a huge fan of yours since reading and listening to Rules of Civility, which was your debut novel, and I also adored A Gentleman in Moscow. But I'm especially excited to be talking to you today about your new Audible Original short story, The Didomenico Fragment. It's about a Renaissance masterpiece, a painting that's literally been subdivided by a family over several generations. Welcome, Amor.

Amor Towles: It's nice to be here. And thanks for having me, Emily. Good to talk to you.

EC: Good to talk to you too. You know, it's funny, I really struggled to boil the story down into that one-liner for the opener when I was preparing for this interview. There's a lot going on here. There's this main character, Percival Skinner, and he's later on in life, and due to some budgeting miscalculations, he's a little bit hard up for funds. It takes place around 2008 is the sense I was getting.

AT: Some vague moment like that. Yeah.

EC: But he's got this idea about how to recoup some cash, and that's by helping a mysterious serious client track down a missing piece of this painting that had belonged to his family and has been literally sliced over the generations into different pieces.

But it was also interesting to me because that painting itself almost becomes one of the characters. And you really served up this amazing art history lesson about the Seven Joys of the Virgin and the Annunciation and how that's a recurring theme in Renaissance art. So I wanted to ask you—that academic rabbit hole was amazing—how did you come to that as a subject for a short story?

AT: First of all, let me say that I've been writing fiction since I was a kid. I wrote fiction in high school. I wrote it in college. I wrote it in graduate school. So inventing stories or thinking about stories has been a part of my life almost for as long as I've been able to read. For me, I got interested in writing at the same time I was learning to read, and the two practices have gone hand in hand ever since. And I'm 55.

So the roots for this story kind of come from two places, in terms of the big elements that you're partly describing. The first is that I was raised in the Boston area and my mother's family comes from old New England Puritan roots, and my grandfather was a classic old, new England WASP, Boston Puritan type.

"When it's going well, yes, you can create something that feels fresh and interesting and surprising and informative to you, even while you're making it. And Percy is a version of that for me."

When I was a kid, we used to gather for Christmas at their house, which was not a mansion, but a nice-sized house where he had raised my mother and her sisters with my grandmother. And so we would gather for Christmas and Thanksgiving, what have you.

When you were there the staircase would turn in that sort of old style, and at the turn and the staircase, there was a portrait on the left and the right side of the staircase, and it was a man and a woman. I don't remember, they were my grandfather's great-grandparents or grandparents or great-great-grandparents, but they were just these old 19th-century or late 18th-century portraits of these two eminent Bostonian types.

When I was a teenager, my grandfather and grandmother moved out of that house as older people not needing the space and moved into a small house in the town that I lived in, Dedham, Massachusetts. And the first year that we went there for Christmas, that they moved there, there were the portraits, but the only thing was that they had moved into this sort of 300-year-old small house with low ceilings in sort of the 18th-century style. And they couldn't fit the portraits in the house in any one place.

So my grandfather, who was eminently practical and rarely really sentimental, he thought that really the best thing to do with these two portraits, which were full length, was to cut them in half, so then when we sat down at Christmas dinner, there was great-great-great-grandma and great-great-great-grandpa or whatever, they were truncated from the waist up, reframed, and presiding over this now smaller, more intimate dining room. God knows where the legs are. I would give anything to have them today.

But anyway, so that happened in my teen years, and you kind of pack that away as "What a hilarious thing to happen." And always, for me, the perfect example of my grandfather's kind of fine version of this... There's some sentimentality there, because he wanted to keep the paintings, but not too much sentimentality. So that's one thing.

So flash-forward a number of years, 15 years later, I'm 30 years old, and my wife and I are, maybe we're even engaged at that point, but we're not married, and we went to Italy, and one of my uncles was renting a home in Tuscany, my uncle and aunt, and we went to visit them. While we were visiting them, the four of us went on kind of this well-known pursuit, which is known as the Piero della Francesca Trail.

Piero della Francesca, one of the early Renaissance figures who invented the fine painting of the Renaissance, had done paintings and on walls and for churches throughout Tuscany, and there was a trail you could go on. You get in your car and you drive and 30 minutes later you'd see one of his works of art in a small chapel, and you get back in the car and drive another 30 minutes and see another one, then you have lunch and wine, cheese, and then go on to the next one.

So we had done this, and one of the paintings was an Annunciation, and the Annunciation is the moment at which one of the angels visits Mary to let her know that she is pregnant with child. I am not an overly religious person by any means. I think that I know as much about that moment in the Bible from the Peanuts Christmas Special as I do from church attendance. But nonetheless that's the moment. And the angel comes and tells her that she is pregnant with a divine child, thus the Annunciation, it's the announcement of the news.

And as we were going through Tuscany and seeing not only Piero della Francesca's paintings, of which he has done a very famous Annunciation, I had begun to see in Florence and throughout Tuscany other Annunciations by other extremely important Renaissance painters. And what really stood out was that unlike many of the religious paintings that the Renaissance painters were doing, this is one which they constantly return to in a very similar format, where Mary's on the right, often seated and reading a book, the angel appears on the left and is kneeling out of respect. The angel often has a flower in his hands. Usually she's in an inside-ish space, sort of like in a room that's on the edge of a garden, but it's open on the garden, and the angel is usually outside in the garden, kind of talking to her through the opening. But time and again, the most famous Renaissance painters, some of those famous Renaissance painters in our history in the West, had tackled this painting using that format.

That kind of fascinated me. I had written notes to myself then, at the age of 30, about what it might mean and what an interesting thing to investigate, potentially to write a work of nonfiction that looks at this and etcetera. Now, so years pass, and now I'm around 53 or so. I was doing a bunch of short stories, which I'll often do in between novels, because while I'm traveling, talking about A Gentleman in Moscow, say, it's not a great time to start a new novel, because you're constantly getting on planes and talking about the last book, and so I'll write some short fiction.

I thought I wanted to write this story about this character in New York, kind of an old WASP type. And I thought, wouldn't it be interesting if that idea of the painting getting cut in half, whether that happened in a family, but it was intentional, where a great-great-grandpa had a famous painting that he revered and loved and has four sons, and so unwilling to give it away or sell it, but also unwilling to show preference over one boy versus the others. He has the painting cut in four, framed in four, and bestowed on his children.

So this is the idea of the story that I started with. And once I started going into it, I was like, "Oh, what painting is it going to be? What painting...?" And all of a sudden, of course, then you're like, "Oh, you know. I know. It's going to be the Annunciation." And then I can go back to this sort of crazy obsession that I had in my 30s about this strange painting and its history and merge these two things. So, suddenly like that, the protagonist is not only a New York WASP, he's also a former curator at Sotheby's, which suddenly makes so much sense.

And so that's the way these things sort of come about. They crash together of little bits and pieces from the past. When I start a story like that, I really don't have much of an opinion about what it's about. Frankly, I don't really think about my novels, what they're about, even though it takes me years to write them. I rarely ask myself that question. It's more of a, is this a rich and interesting set of circumstances that I can begin to investigate as a writer? Then very importantly for me, this isn't true for all writers, but it is for me, do I have a personality and a tone of voice that intrigues me? Whether that's Katey, who's at the heart of Rules of Civility, my first novel, which is first person from her perspective. Or the Count in A Gentleman in Moscow, where it's third person, but really we're hearing his view of the world and his tone, his trials and his poetry through the language of the book.

Same problem poses itself in a way more acutely in a short story, because you have to deliver so much in such a short period of time. And so the question is, who is this person who's going to tell the story? And then once you get a good sense of him, you're off to the races. Again, without necessarily knowing what it's about yet, but having the right person talking about it. That's all I need.

EC: The painting being cut in half. So, I mean, I actually worked at Christie's briefly before coming to Audible, and—

AT: So you know more about this than I do. You should be talking.

EC: Well, no, but I worked in British pictures and then in rare books. I didn't actually know much about Renaissance art, but I was definitely Googling the Annunciation the whole time I was reading this. I went down a total fascination, like you said you did as well.

But I have to say, when I read this and you got to the part where he says he did what an egalitarian father would do—or I don't remember the line, but he cut it into four equal parts—I think I screamed, actually, because I just remembered the conservation efforts that sometimes it took to piece things back together. It was really... It was almost a little bit like this is horror for me, because I don't read horror, but this felt like a little bit of a horror moment for me.

I was going to ask you if you've ever seen that done to a famous painting, but I guess not, to your family painting.

AT: Well, it's interesting you say that. Another obsession of mine, and it's closely related to that, and it's another thing that I've thought about writing about at some point in my life, is there's a very famous painting of Manet's. I'm going to get it wrong, but it's The Execution of Maximilian or something to that effect. And it's about one of the French sort of political... The person in charge of Mexico, but reporting to Napoleon in Mexico, was eventually executed by Mexican soldiers and it was depicted by Manet.

"...With Lithgow I have no hesitation. I think he's a perfect person to play the character."

But for a variety of reasons that painting ended up getting chopped up. And I think some of it was Manet's interest in doing so, and some of it was, I think, in the convenience of framing it in a particular way. And I'm going to get this wrong, the facts, I think, but it's close to this: Degas ended up becoming, was a great fan of Manet's, and obsessed with this painting, and he tracked down the individual pieces that had been taken off of this painting. And it's sort of reconstructed, and that's at the British Museum and is a beautiful thing to see. But again, versions of this have happened throughout history. Paintings that are not deemed world famous yet, they're not valuable yet in the real sense that we think of them, they're not fetishized yet. They're still just objects on the wall that make the room prettier for some people. And maybe there's an owner who has a deeper sense of attachment to that painting. But that's the way a lot of art starts, is that it's decorative.

EC: Right. And then these massive prices that they earn at auction houses, it’s not really what the artists themselves ever thought would happen.

AT: Right. That's all fantasy. So it's quite reasonable to cut off a little bit here or cut off a little bit there, for some people, to make it fit in a particular spot. Now, of course, we look back in horror at that kind of thing. But nonetheless, those kinds of things do certainly happen.

EC: And is Didomenico... So this is something I couldn't uncover. He's not a real painter, is he? Or is he, and I just couldn't track him down in my internet searching?

AT: I encourage any reader or listener of the story to spend as much time as possible tracking down his history. I think that's terrific.

EC: All right. So I wanted to talk about Percy. Poor Percy and his dwindling resources. He is such a snob, but also really lovable and not pompous, whereas his cousin is pompous. He's not pompous. How did you develop that voice? I mean, it was a lot to accomplish in a short amount of time. There's a lot of derision that you've sewn throughout there.

AT: Yeah. It's not me, that's for sure. I think we've all met people who have different tones and different ways of approaching things. And there is that sort of sophisticated person who is a little negative, a little insightful, a little sarcastic all at once, and they can walk into a dinner party and quietly turn to you and sort of suss up what they're seeing in this really cutting way, but yet it seems very accurate. And yet it's shocking all at once, you know?

So yeah, he's sort of trying to grab a person with that tone. There's been money in the family generations ago. He's not sitting on money now. And that's an important part, I think, of the personality. If readers find him at all endearing, that helps. Right? I mean, because he has been humbled in some ways, and that's a part of... But he's still a sharp figure.

I don't know where the voice comes from particularly, but I enjoyed writing in it. It's one of the few cases where having written the short story, I immediately began thinking of other stories that I would like him to tell.

EC: Oh, interesting.

AT: Because I found his angle interesting. Now I'll pause here to make an aside, but I think it's for our listeners or readers that they might find this intriguing, which is that in writing Rules of Civility or A Gentleman in Moscow, and I traveled the country for both books, having the luxury of talking to readers about those books. If you go to amortowles.com and go to the contact page, your emails come straight to me. So over time, you hear from readers about what has affected them in the books. And when someone comes up to me or writes me and says, "This is a sentence or a paragraph or a passage that seemed either wise or astute or particularly poetic. And I wrote it down," or "I sent it to my mother," or "I read it out loud to my husband" or "my wife," whatever.

When this happens, somebody comes to me and says this, 99 percent of the time, the thing which they are reading, this insight or this moment of wisdom, is something I would never have come across, come up with in the course of my daily life. I would never have said it to my children, or suggested it to a friend, or thought about it myself as I consider my own behavior, or said it to my wife. It never would have come up in the course of my daily life. What's happened instead, is that in writing, whether it's, as I say, the Count in A Gentleman in Moscow or Katey in Rules, I've invented a person who I am not. A person has a different personality than me, a different background than me. In both cases, quite profoundly different than me—

EC: Yeah. You don't write autobiographical fiction, do you?

AT: Not so much. And so then I take that person who is not me, and I put them in a situation I've never been in. And while that person with their different background and their different psychology is navigating this circumstance that I've never been in, there's a moment where they may stop and look around them and say, "You know..." whatever it is. They'll rattle off an observation about what they've just observed.

It comes very fast in that moment. I'll be typing and I'll be like, "Oh, well done, Count." You know, "That was terrific. What an insight." You know? "Oh, man." As soon as I hit the period. But that's what it feels like, is it feels like this is insight that has been brought to you by this combination of their background, their personality, and their experience that they find themselves in.

"It's been nice to have readers reach out to me and say that it has helped them in some small way navigate this time or their own experience suddenly is more in harmony with the Count's experience than they had ever imagined, just like with me."

And so when I say finishing "Didomenico" and wanting to go back and take Percy into another situation, whether in form of a novel or another short story, it's partly because of that I don't think the way he thinks. I don't live the way he lives. But when I put him in a situation, I find him both insightful and entertaining to me. I know that sounds really vain. Right? For a reader, like, "Wait, he's entertained by his own characters?"

But it's not vain because I don't really think of him as myself. And you wouldn't make the connection, that that person is me. But it's one of the gifts of the creative process, that yes, the artist can be entertained or moved or made more wise by their own imaginative output. And you got to be a little disciplined about that too, because you got to be prepared to edit and cut and drop and recognize something is maudlin when it's maudlin, or cliché when it's cliché. But when it's going well, yes, you can create something that feels fresh and interesting and surprising and informative to you, even while you're making it. And Percy is a version of that for me.

EC: Whenever I recommend your books to friends, I always describe them as "epiphany rich," which kind of makes sense, hearing how your creative process works, that you're letting your characters create observations that don't always feel like they immediately come from you. They come from them. So that makes a lot of sense to me. I feel like every page there's something that feels a little bit like, "Ah," a very refreshing observation that I had never thought of before.

AT: Great. Thank you.

EC: So I wanted to quickly talk about the casting for The Didomenico Fragment.

AT: Oh, yes.

EC: Yeah, when you visited Audible last year, you said you were hoping for someone that could do sort of New York City patrician, and now we have John Lithgow, who is a Mayflower descendant.

AT: When you emailed me to say that, "We found John Lithgow and he's agreed to do it," my immediate response was, "Perfect!" I think it was a one-word email, you know? Because I can't imagine a better person. And you write it, you hear it yourself, you imagine what it might sound like, and it's a tricky thing. When they bring it to life, you may say, "Oh, they did a great job bringing it to life. It doesn't necessarily sound exactly like I would have wanted or what have you," but yeah, with Lithgow I have no hesitation. I think he's a perfect person to play the character.

EC: Yeah, me too. I'm really looking forward to it and looking forward to our listeners being able to pick it up.

I wanted to ask you about A Gentleman in Moscow specifically because of right now where we're on a phone call through our video chat because we're at home and we’re quarantining. But I've seen so many people on my social feeds talking about this book and how they feel like they can relate to it and they weren't expecting to relate to it.

But for those of us who are fortunate enough to be able to quarantine and isolate at home, it does feel a little bit like a gilded cage. This isn't necessarily what you expected a crisis like this to feel like. I just wanted to see, did you ever imagine that one of your fictional renderings would ever feel prescient in this way?

AT: Absolutely not. No. People have reached out about that, readers, and it's very moving and satisfying as an artist to know that a character you've created or a set of circumstances you've created resonated with their own experience. For those of you who have not read or listened to A Gentleman in Moscow, the premise is that a 50-year-old aristocrat in 1922 is sentenced to house arrest in a fine hotel across the street from the Kremlin. In that book you spend 30 years in the hotel with the Count as he navigates his inability to leave the building.

And that book came out almost five years ago. So yeah, it was certainly not a byproduct of—

EC: No idea, yeah.

AT: ...anything like this. But yeah, I mean, there's obviously when you set yourself a task of telling that story, inevitably you're asking yourself to, in taking on this person's circumstance, to walk the halls of the hotel, and I like to think of it as that when he walks into a hotel in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, he's lost his family, he's lost his possessions, he's lost his social standing. And in a way what's more profound is that he's watching as everything that he cares about in Russian life is being uprooted by the new regime systematically. That's kind of how he begins his internment in the hotel. And over the course of his 30 years, he must establish new relationships. He must find new causes for happiness, however small. And ultimately he must find a new sense of purpose.

That's really what that book is about in a big sense. And yeah, me personally. That investigation, which is natural to the telling of that story, has a harmony that I never wanted in my own life, just in terms of, you're trying to make the best of your times and find elements in your daily life that replace those pleasures and relationships and sense of purpose that our normalcy provided us.

We're all kind of moving back as carefully as we can towards that normalcy, but in the interim we've all had to kind of reinvent different aspects of what we do and how we interact.

And yes, the book is an investigation of that in many ways. It's been nice to have readers reach out to me and say that it has helped them in some small way navigate this time or their own experience suddenly is more in harmony with the Count's experience than they had ever imagined, just like with me.

EC: Yeah, completely. I'm not sure I would have realized this until now, reflecting back on it, but you did a really great job of depicting the evolution of cabin fever and the way that your mindset changes over time. And I think it's just... It's really spoken to me. I can't believe how on key that's felt here.

Also, it's interesting because you assume when a pandemic hits, or one would assume, that it might feel more like sci-fi than it feels like historical fiction. And so it's interesting that your historical fiction work is the one that's connecting with the current moment, but—

AT: Yeah, that's true. That's fascinating, yeah.

EC: Are there any other genres that you'd like to dabble in that are outside of your normal zone?

AT: No question I will continue to kind of explore... I mean, you kind of get a sense, I think, in looking at my transition from Rules of Civility to A Gentleman in Moscow, that I like to keep shifting the tiller. And my new book that will hopefully be available through you.

But that book is about three 18-year-old boys and an eight-year-old boy who are on their way from Nebraska to New York City in 1954. That book takes place over 10 days. So it's a very different kind of experience than certainly A Gentleman in Moscow, which is a sophisticated figure over 30 years. These are very unsophisticated 18-year-olds over 10 days and in 1950s America, which I think will be fun and I'm enjoying writing it, but it will be, again, a very different thing.

There's no question in my mind that in my time, in my life, I will turn my attention to the noir environment, whether it's to write a detective book or a murder story or something suspense, but I love, I'm deeply steeped in the history of American noir and love it, having been a fan of Chandler and Hammett, and Humphrey Bogart in film. And so I'd love to go and explore that more closely as a writer.

EC: Well, Amor, it's been such a pleasure talking to you and I can't wait for our listeners to enjoy The Didomenico Fragment as much as I did. Thank you so much for joining us.

AT: Thank you for having me, Emily. It was great talking to you.