Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

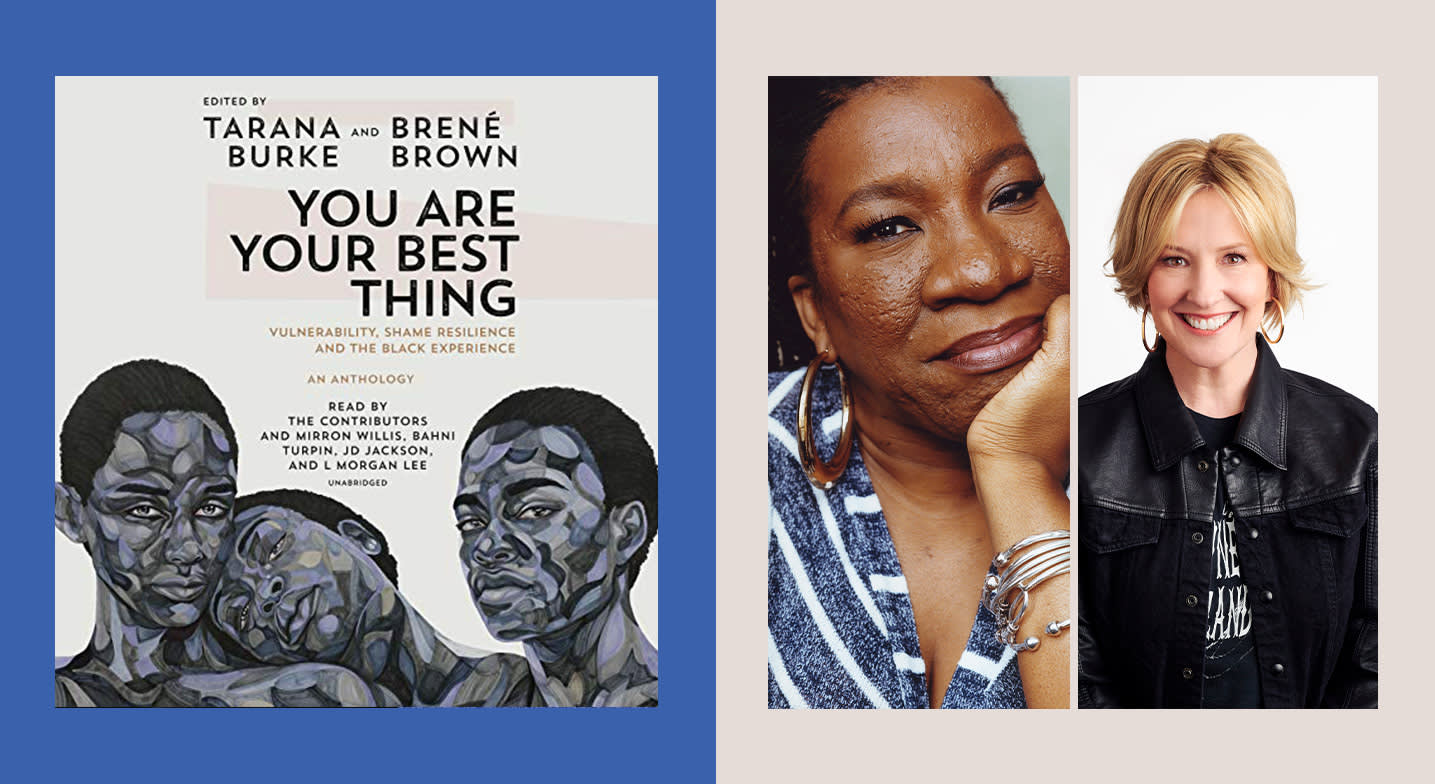

Rachael Xerri: Hello, I'm Audible Editor Rachael. Today I have the honor of speaking with Tarana Burke and Brené Brown. Tarana Burke is an activist and the founder of the Me Too movement, and Brené Brown is a researcher and author of five number-one New York Times' best-selling books. We're here to talk about their collaboration, called You Are Your Best Thing: Vulnerability, Shame Resilience, and the Black Experience. It's an anthology of essays by some incredible authors, celebrities, and cultural figures. Just to name a few names here we have Kiese Laymon, Imani Perry, Laverne Cox, Jason Reynolds, and Austin Channing Brown, among so many others. Tarana and Brené, welcome and thank you for being here.

Tarana Burke: Thank you for having us.

Brené Brown: Thank you. Excited to talk to you.

RX: Likewise. Okay, so, Tarana, I'm going to start with you. What led up to you wanting to put together this anthology and why did you want to work with Brené? I know from some of your previous interviews that you and Brené are friends.

TB: Yes, well, that certainly started it, but also I wanted to do the book because I really wanted to have an offering for Black people in this moment where there's so much reckoning around race in the country, and so much discussion about how people, other than Black people, can be better and how people, other than Black people, can change their lives to make Black lives matter more in this country. But there was, in my opinion, too little conversation about how Black people can process in this moment and how we needed to work through the trauma of holding all of this violence and this lack of concern in our bodies and our minds and our spirits.

"...There was, in my opinion, too little conversation about how Black people can process in this moment and how we needed to work through the trauma of holding all of this violence and this lack of concern in our bodies and our minds and our spirits." — Tarana Burke

This book felt like the right offering in this moment to help us think and work through some of that. If I'm thinking about shame, shame resilience, vulnerability, courage, wholeheartedness, any of those things, Brené Brown is the person who comes to mind first, but also, she was the person who I was talking to, like a lot, during that time, and it just made sense that when it came up for me I wanted to have a conversation with her because her work had been so, so helpful for me over the years. I thought, if we expanded it to make it more clear how the Black experience fits into it, that it would be even more helpful for Black people in this moment and for other people who are pushed to the margins, other people who may not feel like their stories are represented or seen, their experiences with vulnerability or shame or shame resilience are not seen.

RX: Brené, what was that conversation like for you, when Tarana first approached you about putting together this anthology?

BB: Well, we had been on a text-tear for, I don't know, several weeks about home decorating, about wallpaper and paint colors, and so when I saw the text come up I have that thing on my phone where you can see someone's text but you can't see what it says. So I'm like, "Oh my God, she's finally decided. I wonder what she's gonna do?" And then when I pulled up the text I think it said, "Do you have a minute? Can we talk?" And I was like, "Mmm... Doesn't sound like decorating but maybe it's like a very serious decorating question." So I said, "Sure, let's do it right now.”

I'm in the car, and my husband was driving, we're always going back and forth between Austin and Houston, and so we jumped on the phone and she just kind of laid what she laid out for you. She said, "I have found a lot of helpful things in your work. It's been affirming for me. Your work on shame research gave language to something that I had been doing with girls and young women and women in the sexual assault work I've been doing. I thought I was the only one who used the word shame." And I was like, "Yeah, I think it was just the two of us, basically."

And she said, "But sometimes, honestly, I have to kind of contort myself to find myself, not in the research but in your stories, and how you bring the research to life, and I'm wondering if there's something we can do together so that people who are living the Black experience don't have to look so hard to find themselves in the narratives."

This was not the first time that I had thought about this or received that feedback. But it was the first time I had received that feedback from someone who also said, "And I've got an idea about how we can do that." I was honored and anxious, and I think that all came out as a "Hell yes, let's do it," followed very quickly by, "You know we're both on writing deadlines for other books, right?"

TB: Right.

BB: Yeah.

TB: I think we really severely downplayed the busyness of our lives and how big it is to put a book out in the world.

BB: You think?

TB: Phew.

BB: Do you think we did that? Yeah, I think we did that. But it was just so exciting and it was so hopeful, and I asked her a lot of questions, and the thing that she said that just—I mean, when she said, "Hello," sealed the deal—but when I said, "What's your hope?," she said, "I want this book to be a soft place for Black folks to land. Antiracism work is really important. I'm not interested in antiracism work that doesn't embrace the full humanity of Black people, and I want this to be a book that embraces the full humanity of a diverse group of Black writers and thinkers." That just pierced my heart in a really profound way, and so I said, "Well, I'm willing to put aside what I'm working on right now if you can and let's do it."

RX: Thanks, Brené. That's actually a really good segue into this next question. Tarana, you talk about this idea of Black humanity and its role in antiracist work. Can you elaborate, to our listeners, what you mean by Black humanity and its relation to this anthology?

TB: I think Black humanity's pretty self-explanatory. It's humanity, but of the humanity of Black people. Our lives, our material lives, not just what we represent or what you see in the media or the snippets that you get in pop culture of who we are but how we deal with trauma, how we overcome trauma, just the full spectrum of who we are, as human beings. We're more than hashtags and we're more than marchers and we're more than protesters and we're more than stereotypes. A lot of people only deal with the pieces of who we are because it is much easier to take us in bite-sizes, and I think we do that with people, right? People don't tend to engage fully in other folks' humanity. We are so busy living our lives and trying to get through life ourselves, but in this moment where there's this particular attention being paid to the lives of Black people and we have this mantra that people...

You know, I was in a restaurant the other night, for the first time in God knows how long, and it had a huge sign in the window that, it was etched, that said "Black Lives Matter." It was a beautiful etching on the glass and I thought, "That is so fascinating to me that they have this on the mirror," and I kept looking around the restaurant and it was… I mean, what does a restaurant do, right, to show that Black lives matter? But it just felt a bit contrived, and I wonder what the lives of the Black people who work here are like. There's some, probably Black, person in the back. I didn't see anybody on the floor, I didn't see anybody on the staff, and we were one of two tables that had Black people in the restaurant.

So, there's a lot of symbolism that was happening, a lot of talk that was happening, a lot of studying that people were doing, but not a lot of engaging in who we are as people. And I think this book, when we started thinking about who we wanted to write and what we wanted them to write, we even attempted in the beginning to put ideas next to people, and that proved to not even be necessary and even wise, right? Because once we had the conversations with the authors and said, "The book is about vulnerability, shame, and shame resilience," and people went in their own directions and it was beautiful, and wonderful, and exactly what we needed.

RX: Absolutely. There are so many human moments and so many breathtaking moments in this anthology. Just taking a moment to be a little bit vulnerable myself, there was this specific part in Austin Channing Brown's essay, "This Joy I Have," where she talks about the fear of losing loved ones, specifically because of racism, and it resonated with me.

My partner of seven years is Black and I have a fear every time he walks out the door or takes a cab or speaks to an officer that he'll be in danger, and listening to Austin's essay really confronted me with the fact that as a White woman, that fear that I feel for my partner is just one fraction of what someone who is Black and whose family is Black experiences every single day. Not just for their loved ones but also for themselves, and there are so many moments like this in these essays that have also sparked conversation between me and my partner at home about his relationship with vulnerability. So I know this was a really long aside but my next question is—

TB: I think it was a great aside though because—

BB: Me too.

TB: ...I loved that you used the word that it "confronted" you. That is a great way to put that.

RX: I think there's a lot of work that needs to be done by allies, just consistently to learn and to listen. I've learned a lot from this anthology. My question is, for both of you, if there was a specific essay or moment or series of moments that resonated with you? Tarana, we can start with you.

TB: Oh, gosh, every time I'm asked this question, I feel a little bit differently. Well, definitely my daughter. I bring that essay up a lot because it was... I actually, unlike what people might think, I did not invite my daughter to contribute to the book. Brené did.

BB: That was me.

TB: Yeah. Brené was like, "What about Kaia?" And I was like, "Oh, okay, that would be great." I know my child is a great writer and is very expressive and very emotive, but the actual essay, seeing all the words put together on the page was jarring for me to take in and to read. We have a very good relationship but engaging them as an adult, an adult human being in the world, was an interesting experience. I read Marc Lamont Hill, who is my friend as well, I read [his] essay the other night because somebody posted an excerpt from it online and it was a line I didn't remember, and so I went back to read it and I was like, "Man, this is really good." It's just, I want so many other Black men to read it. It's really, really so good. I find new things all the time. I know I'm biased but there's just so many little gems in it.

RX: Right. How about for you, Brené?

BB: Very much like Tarana, I think there's something for every emotion that I experienced, there's something for every time. I don't know that I have a favorite. I don't think I've shared this in an interview yet, Tarana, but you can remind me, but the one I was most anxious about was actually Tarana's.

TB: Oh, really?

BB: Yeah, because we're friends and I love her and she was as vulnerable in her essay as I've ever seen her. And I felt this pull–push of, "God, this is amazing and this is exactly what we need to be talking about, for all women but especially for Black women and women of color." And then, at the same time, I was like, "Don't do it!" You know, I just felt maybe, I don't know, protective.

TB: Yeah, you did kind of express that. You were like, "Are you sure you wanna put this out? Are you sure this is where you wanna go?" And I wasn't sure.

BB: You weren't sure, and it was probably reflective of the fact that you talk about the plight of actually being human and not, like, a superhero and getting sick, and those are really shame-triggering things for me and I know how hard it was, so I was just swept away by all of it at different times, for different reasons. I think Tarana wrote hers last, or at least I read yours last. Did you write it last?

TB: I wrote it last. No, you're right.

BB: Yeah, yeah. It was just beautiful, honest, and unflinching and...hard, and helpful for me. Healing in a big way, yeah. You had that text at, you know, midnight, "Do you want me to read Kaia's first?"

TB: Exactly, I was like, "Please."

BB: "Or do you want to read it?" and you're like…

TB: "Please read it first."

BB: And then I remember just sending a text that said, "OMG, read it."

TB: There's so many little stories here, I do appreciate that. I was so nervous to read it and finally Brené… I kept putting it off and Brené was like, "Do you want me to read it first?" And I'm like, "Please, thank you."

BB: "OMG, read it, grab tissue."

TB: Yeah, certainly.

RX: Brené, I have a follow-up question too. How is working on this anthology and hearing these stories shaped or informed how you'll approach your work moving forward? Specifically taking note of how to make sure that Black humanity is front and center in antiracist work.

BB: I don't think my work will ever be the same, because I'm grateful that I've always, for 25 years, always had a very representative, very diverse sample, and that comes from being trained as a social scientist and a researcher within a school of social work. I spent my entire academic career critiquing articles based on really White samples that then the author would make a leap to try to generalize to a broader population and you' just couldn't. I remember being an undergraduate social work student a million years ago and learning that all of the original breast cancer research was on men.

"...Shame cannot survive being spoken. Shame only works if it can convince you that you're completely alone, but once you know you're not alone, that other people have lived through that or are experiencing that, it takes down shame at its knees." — Brené Brown

TB: What?

BB: Yeah.

RX: Wow.

BB: And so I come from a very politicized background as a social worker. I always had very diverse samples, and so it made sense to me when Tarana, and others, have told me the research rings deeply true: "Your expression of the research in the books leaves me trying to find myself in my lived experience." A lot of times I explain the research. I'll lay out the data, but then the stories I use to illuminate it are my own stories, just because I have access to the backdoor, I can say, "I was really feeling like this but it came off as pissed off." And so, I think moving forward I'll continue my commitment to diversity in the research samples, but I will make sure that the stories used to teach the research are representative. And not just my stories. I'll include my stories because I think that's important because the backdoor piece is helpful, but it won't end there, moving forward.

RX: That's great. Thank you. Let's talk a bit about the incredible performances in this anthology. Tarana, I thought you did a masterful job as well. Most of the contributors in this anthology actually narrated their own essays. One that comes to mind is Tanya Denise Fields's performance of her essay "Dirty Business." I thought that was just so impactful. Tarana, what was it like to both write and narrate your own essay?

TB: I will tell you that I was not ready for narration. I did write my essay last, I had read a ton, you know, the whole book. Not in the order it is now but sort of as the essays came in, we were editing and going back. So I'd read them several times and in pieces and then the whole thing. So when I sat down to narrate my story, I'm also in the middle of writing my memoir, and I stopped that to write the essay, and then came back to it. When I sat down to read my story, I had not read it, my own story, in a while. And it destroyed me, quite honestly.

And Kaia and I did it on the same day, and my daughter was at my house and they arranged for us to do it [the narration] the same day. I did all the technical stuff and we did the tech check-in and I found the best place in the house for the sound quality, and we'd spent, like, 30 or 40 minutes getting all that done, and I settled in and we were finally ready to start and I started reading it and probably 10 minutes in, I burst into tears. I was like, "Oh, boy. This was why they gave you a script, to read it beforehand." I was just so busy, I didn't have a chance to do any of that.

But I really did enjoy the experience and I really love the fact that you get to bring your own story to life, so you know just where to make inflections in your voice and where to emphasize, right? I love that part of it, and I had a really good producer. She walked me through it, she was very patient. She stopped and took breaks and she encouraged me to take breaks. She was really, really, really good, so shout out to her, but yeah, it was quite an experience and then I warned my kid. When I finished I was like, "Baby, you gotta prepare yourself. Let's just take a beat and get you prepared," and then I went into mommy mode and kept running back and forth with water and snacks and checking in and checking, "Are you okay? Are you okay?" And they had a similar experience too. It was like, "Whoa! I was not ready for what it was gonna feel like to say these words out loud."

I've been hearing the responses from people who are listening. It's so different to hear the responses from the people who have listened to the book as opposed to read it. Right?

BB: Yes. And I've listened, and as someone who's read all my books I could not believe the level of talent on the audio. Holy crap.

TB: Oh, I gotta go listen to the whole thing. I'm gonna listen to it on my trip to LA next week.

BB: Oh my God, just gird your loins.

TB: Yeah, oh.

BB: Yeah, at least you're gonna be on a flight, because you think they're emotional to read... I mean, Tanya's is a great example... Oh yeah, it's not easy to do that but I was blown away by the quality of the voice performance. I was gonna say, "Weren't you?" Weren't you, Rachael? Come on.

RX: Yeah, absolutely. I think there were so many moments where I had to pause because it was just so heavy and especially, like I mentioned before, I've been listening along with my partner as well, so wanting to give him some space to really absorb it, because it is some heavy stuff. Especially with the themes ranging really from everything from our broken healthcare system to being a survivor to domestic abuse. I was absolutely blown away by the performances.

Brené and Tarana, was there anything new that stood out to you when you listened to the anthology versus reading the essays in print? And Tarana, you can answer this just from the lens of what you've listened to so far, your essay and your daughter's essay.

TB: Well, I'll let Brené answer first because she's listened to the whole book.

BB: I think, just how deeply courageous... I mean, that whole idea of, "Speak your truth even if your voice shakes." You could tell that... Tarana has said this a lot in the interviews we've done and I had it in my heart but I didn't language it, and now, once you'd said it, Tarana, it makes so much sense.

There's such generosity of spirit in this book. That these folks would come and share these stories that are so deeply human and personal. I just kept thinking as a shame researcher, shame cannot survive being spoken. Shame only works if it can convince you that you're completely alone, but once you know you're not alone, that other people have lived through that or are experiencing that, it takes down shame at its knees. And so, I thought, in just the speaking of these stories, and the writing of them as well, but also just the speaking of them is an act of profound shame resilience in itself.

TB: That's a really good point and that's probably why I had an emotional reaction, right? I always talk about the power of getting the story out of your body. Even if it's not necessarily to an audience or to a bunch of folks.

The first person you tell your story to is yourself, and there was such a personification of that, right? It was like, "These words are coming to life right now and right in front of me." And Kaia, because they're my child, their voice is particularly connected to and I have an affection for, so hearing their voice say the words really, really affected me. I'm like, "I just can't listen," it sends me back to that place of wanting to do something to fix something, to just, anything to make what they're saying not be true. But then there's people like Jason, who I could listen to read the phone book. Just a talent in and of itself. You made a great point about them speaking out loud.

BB: In the research, one of the elements of shame resilience is speaking shame, and I do think there's a power in spoken word around this affect or emotion, particularly.

RX: Definitely. And moving on to this next question. Tarana, I think you've said this already, that your intention for this book was to give Black people a soft place to land, and I love that description but elaborating on that, who is this book for and what do you want listeners to take away from it?

TB: I think there's multiple audiences for every book. I think the first audience for this book is Black people. I think that it is an offering to us, to Black folks, that says, "Here is a reflection of your humanity that you don't often get to see in mainstream, in books, in pop culture, what have you. Here are other people who think and feel and respond in similar ways to you." That's important, that's deeper than representation, right? It's reflection. But I also think that after that, other groups who deal with similar marginalization to Black people will find themselves needing and grateful for some of these stories, and they will resonate in similar ways. And then I think White people, I think that everybody else, I don't know who the everybody else is, but this is about connected humanity, and I've been saying that so much lately that I almost have to giggle at myself because 10 years ago I would have said, "That person is a sucker."

So kumbaya, but it is true. I think that, as I get older and hopefully wiser, what I see, this interconnectedness that has kept us alive in the Black community, is also necessary in life; we're doing all this work. Whether you're working on climate change or gun control or ending sexual violence or advancing Black lives, whatever it is, it really is, ultimately, about advancing humanity. And we have to have vehicles to do that, we have to have containers to hold those stories, we have to have tools to do that work, and I think that this is both of those things. It presents a container to hold the stories that we don't often hear, but it also is a tool for that level of connectedness that is absolutely necessary if we're going to get to the place that we, ultimately, are saying we want to get to, right? Where our shared humanity matters, and not because we don't see color and not because we're just all one, but because we deeply understand that we're not all one but we're still connected. That "I do see your color and you still matter." So, I think it's still important for us to have books like this in order to get to that place.

"Whether you're working on climate change or gun control or ending sexual violence or advancing Black lives, whatever it is, it really is, ultimately, about advancing humanity." — Tarana Burke

RX: Absolutely. Is there anything else that either of you would like to say to our listeners?

TB: I'm just appreciative. I'm glad that people are receiving the book well and are hearing the message and the message is resonating with folks across the board, from all kinds of backgrounds and all walks of life. I'm really happily, pleasantly surprised that folks are getting it. I was nervous about, you come out with a book that's not self-published and say, "Well, the first audience is Black people," and people are like, "Oh, cool. That's cool. I can read it too, right?" I'm like, "Absolutely." But that people can hear that and understand what I mean by that, it, to me, is symbolic of where we're heading and where we're moving and the possibility and hope for the future.

BB: Yeah, everything that she said. There was a moment too, one of my favorite moments in this process—because there was also a lot of tears because we're trying to crash a book, in the middle of writing other books—but there was a moment where we had gotten probably, maybe the first batch of essays, we had eight or ten, and I called Tarana and I was like, "Oh God, what do you think?" And she said, it was so funny, she just said, "I'm learning so much about Blackness." And she went on to say how grateful she was that we were very intentional about… People always say, "Black people are not a monolith," and "women are not a monolith," but is that reflective in the work people do? And I think, in this case, it is reflected; there are so many different voices with different experiences. And she said, "What are you learning?" And I was like, "I am learning about the Black experience as well, but I'm learning a lot about my relationship with my family, mostly my parents."

It was just this moment where, I don't know, I just go back to inextricable connection and our inextricable liberation.

TB: Absolutely. Inextricable liberation. I love that.

RX: Thank you both so much for being here today. I think it's been a really great conversation, and for anyone listening in, you can find You Are Your Best Thing on Audible now.

TB: Thank you so much for having us. We really appreciate it.

BB: Thank you so much for taking the time to interview us and we're excited it's available on Audible. I do think there's a lot of power to speaking this content, so thank you.