Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

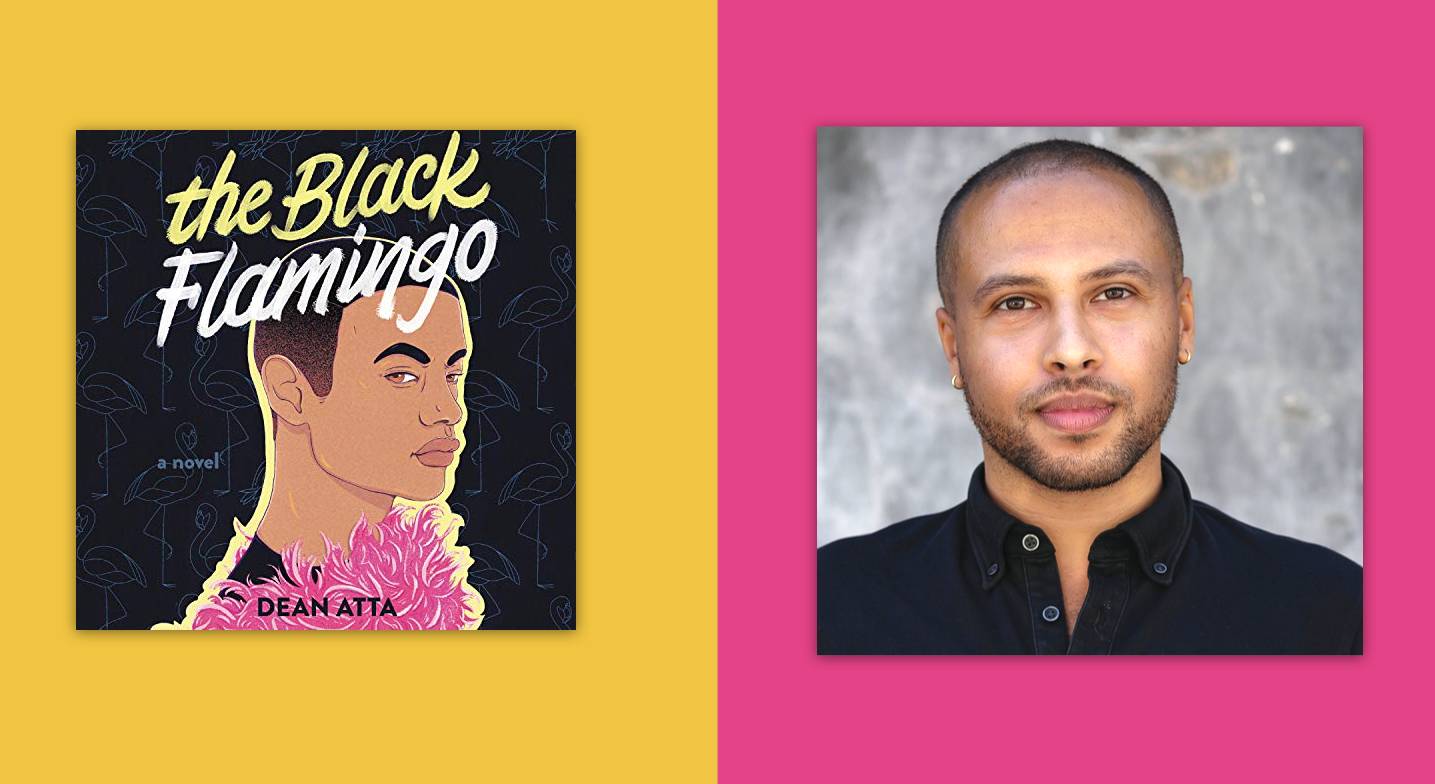

Abby West: Hi, I'm your Audible editor Abby West, and I'm here today with Dean Atta, a writer who in the last few years has been named one of the most influential LGBT people in the UK, as well as one of the UK's finest poets. He is also the author of The Black Flamingo, his debut novel told in verse about a boy who comes to terms with his identity as a mixed-race gay teen, and then truly finds himself as a drag artist. Welcome, Dean.

Dean Atta: Thank you. Thanks for that lovely introduction. It's nice to hear the accolades and the book being summarized so beautifully, so thank you.

AW: I'm very glad you found that satisfying because it's one of those things I always have difficulty with folks whose identity is so tied to their work and how people perceive them. So when I do those kinds of intros where it's like, "Named as one of the most influential LGBT people," do you own that? Or how do you feel about that? Sometimes people are like, "Ugh, move on to my work."

DA: I think especially as a Black man, to be an LGBT role model is important because I didn't have many Black LGBT role models when I was a teenager and growing up. If I can be that for others, and also you could focus on one part but I think it's interesting to look at the intersectionality of my identity. Whether we're talking about Pride or we're talking about Black Lives Matter, I intersect both those ideas and I stand for those things very much, so I want to do both at once and not have to choose one or the other. And with my mixed-race identity, like my mom's family's from Cyprus and my dad's family's from Jamaica and I was brought up in London in the UK, I don't feel I have to choose between Cyprus, Jamaica, or the UK. I can represent them all simultaneously.

AW: I love that. And going into the fact that your character in The Black Flamingo, Michael, is also part Greek Cypriot and Jamaican, and you are also, how autobiographical is The Black Flamingo? Are we going straightforward autobiographical?

DA: Not straightforwardly autobiographical, because when I was Michael's age, we had a very different climate for LGBT people in the UK. Our government had passed a law called Section 28, which meant schools were not allowed to talk about same-sex relationships or families with same-sex parents. And they couldn't have materials such as my book in schools. It was seen as promoting something that was other than the ideal family. It was illegal for teachers to teach such material, to talk positively about these kinds of things, so that really colored my childhood.

I needed to tell one happy story to go some way to addressing the imbalance of how [Black queer] stories are told, whether they're told by us or by other people.

Michael is blessed because he's a teenager today, and today there's a lot more respect and acceptance and celebration of LGBT identities and people and families. And so for me, I wanted to write it set during today because I knew for Michael it could be a lot happier and more positive experience to be growing up and realizing you're gay than it was for me. I had a lot more turmoil around that, but Michael doesn't and so I'm glad I get to write that version of the story.

AW: I love that because a lot of the reviews and what I felt in listening was how uplifting it was, and that seems like a deliberate choice.

DA: That was the goal. I wanted to write a queer fairy tale where no one dies and no one's horrifically beaten, no one gets kicked out of their home. We have those stories and we will still have those stories because those things still happen. But for me, I needed to tell one happy story to go some way to addressing the imbalance of how our stories are told, whether they're told by us or by other people. And when I say us, I mean Black queer people. I feel like often we, whether it's who commissions those or who makes those movies, the tragedies always seem to get the money, always seem to get the commissions, and the fairy tales and the happy endings don't always get the airtime. And so I wanted to make sure that there was at least one more happy story for Black queer people in the world.

AW: We talk about this in the States as well. Black pain is what people gravitate towards wanting to promote, and Black joy is less so, and it feels the same for the LGBT community. I don't know why it is that we all gravitate to the grist and the pain more than joy.

DA: And I worry about it because it paints a picture of us as being able to withstand pain. And so when pain is inflicted upon us, it's seen as less tragic, but actually it's incredibly tragic—even if we're not on the receiving end of the pain—to witness that pain, whether it's in movies or real-life footage. And so I don't take that lightly and I don't want to put more of that in the world, unless it's absolutely necessary for the story I want to tell. And for this story, it wasn't necessary. What was necessary was joy.

AW: I think I know the answers to this, but why this story and why for the YA audience?

DA: Because I think drag is so fun. And I think young people love drag. A lot of people love drag, but I think your teens is a time of experimentation. It's a time of looking at your identity, whether that's through drag or just what clothes you're going to wear, how are you going to do your hair, whether or not you'll wear makeup, what you identify with, whether it's the music you listen to, or whether you're a skateboarder or whether you're this or that. There's so many ways of playing with identity as a teenager. It was a good way to represent that in a quite an extreme way. I think playing with gender is still seen as fairly extreme for a lot of people, so I wanted to see how empowering it could be for Michael. I've done drag myself, but I didn't do it until I was in my 30s. And I was like, "Wow, I really missed out. I should have done this earlier because it's so much fun."

In UK we have a very interesting kind of drag scene. It really plays with gender in lots of different ways. We'll have drag kings celebrated as much as drag queens, and there'll be people who don't identify as a king or a queen, but play with gender in their performance in lots of different ways as well. There's a fairly good representation of people of color in drag, especially in a city like London. I wanted to give a flavor of that because we can't go into the whole history of drag. We're telling one boy's story, but I wanted to give you a sense of what he's stepping into and that the possibilities for him are vast.

AW: This is so much more than about sex or sexuality, right? It is about coming of age, about finding yourself, about finding self-love. And you do talk about the intersections between homophobia and racism. Are these conversations things that you feel like you've nailed or that you're still evolving on yourself, that you're having new realizations, that this is an extenuating conversation? Not like, "Hey, you’ve nailed it."

DA: I think the language, the vocabulary, and the depth of our understanding is constantly evolving. I felt like I knew what I knew when I set out writing the book, but as I met readers and spoke to people about the book and how it resonates with their own experiences, I realized it's kind of speaking to other things that I wasn't even fully aware of.

There are some people that kind of slip up when talking about this book and think it's about a trans character, but Michael isn't trans. He's happy with the gender he was born into. He's male all the way through the book, but he feels that a male identity is quite restrictive in terms of the expectations of boys to be tough or to play certain sports or to act or dress a certain way. It's not that he doesn't want to be a male, it’s that he wants that to be a more open thing. So it's not like you have to dress a certain way, act a certain way, or like certain things just cause you're a boy. That's never him saying, "I don't want to be a boy." It's just saying, "I want to be free as a boy and a man."

I think the way it resonated, though, with trans readers and people who want to have a conversation about trans identity—because it doesn't go there necessarily, but it kind of touches upon some of the similar, kind of coinciding issues that a trans person might come up against—that's been interesting for it to enter that realm of conversation. But there are other books that deal with that head-on.

Being involved in that and seeing the awful transphobia that's out there, from some big-name authors and people in positions of power and politics and all sorts of arenas, I think we need more trans representation out there in literature and beyond as well because we can't have other people tell us who we are, telling our stories, and I say "us" again in a kind of umbrella term, the LGBT community now.

AW: What is that like in this moment in time to have people, authors, big-name authors, who don't show up in the way that you might hope they would in terms of their stances?

DA: I wonder about that because I sometimes think silence is a very violent thing as well, but there are people who maybe should stay silent on issues that they don't understand and should amplify the voices of those that do or should do some reading because there's so much literature out there, whether it's in fiction or nonfiction. You can really educate yourself. There are people giving, they're spending time and energy to educate others. Often, we don't look to the resources that exist; we just turn to the nearest trans person or the nearest person of color to educate us. I don't understand why people do that. There's so much out there for us to learn from already. We don't need to make it the labor of the trans people in our lives or the Black people in our lives or the queer people in our lives to educate us because the books are out there. Do some reading, or listening in the terms of audiobooks.

AW: That's the case, it just takes a little extra work and a thoughtfulness that sometimes people are... This is an extended conversation, especially in the last three weeks here in the States, and I think globally now, that idea of doing the work yourself, but also listening and talking to people and not being so afraid of getting it wrong, but being open to some criticism.

DA: Being humble when you do get it wrong and then listening to the criticism, like you just said.

AW: Yeah. So let's talk about this US edition of the audiobook, which is delightful. There's so many things to dig into here. Let's talk a little bit about the differences between the UK edition and the US edition, because something I found was how universal it felt. It's like listening to something that is set someplace that I am not, and I'm not super familiar with, but everything about the character's sense of being in self and concerns is resonant. That felt like something you worked hard at.

DA: Definitely, and worked with my editors on as well. For both editions, the UK and US editions of the book, having white female editors was really interesting because it meant it was going through them to the readers. Do you know what I mean? They had to understand it, and by them understanding I think it does universalize the experience a bit more, because if I didn't have them as the filter, it might be something that just Black queer people would read and understand. But having a straight white female editor edit me, a Black gay male writer, it's quite an interesting partnership. It really aids understanding for them, the readers that come to it. And so that was not always the most straightforward relationship. There were a lot of questions and answers that could get tense sometimes. But I think we all came through it really graciously. And again, it was a learning experience for everyone involved and I'm really grateful for what I learned. I know that my editors are too, so I'm really happy for that experience.

…Poetry verse novels and poetry in general are meant to be said aloud… it exists in the air and it's lovely when you can put it out there…

The main differences with the US edition are just the specificity of very UK-centric terms or the high school system in the UK being different to the US, so having to adapt how we spoke about that and things like football and soccer, making that translation. But for the most part, I think Michael's voice stays authentically Michael's voice. And you can hear that voice because I get to narrate him in both cases. It was really fun for me to do that. To have Michael come through me is really exciting as a performer as well as a writer, so I really enjoyed that experience of recording the audiobook. I think it gives you a sense, even if you don't fully understand it, when you hear me say it. It's probably clearer than even reading it on the page.

AW: And I think the audio narration just works so well for verse. It's so natural. How, if it did, does it, did it differ for you narrating it in the studio versus your stage performances? How was that different for you? Because now you've done it twice for both editions.

DA: It actually helps with the editing because the book isn't fully finalized. We're recording the audio, but the physical book hasn't gone to print. So if in the recording of the audio we realize that I'm not able to say something the way it's written in the most fluent and fluid way, then we'll say, "Let's change how it's written." And so that's been really good to be able to go back to the print book and be able to change that based on how the audio recording went.

That isn't how I knew the process was going to go but it was such a wonderful experience to see both texts, the audio texts and the written text, with them being able to adapt to each other in that way. I think poetry verse novels and poetry in general are meant to be said aloud, so whether it's hearing me say it or reading it out loud to yourself, I'd recommend that with any poem or any verse novel, because I think it exists in the air and it's lovely when you can put it out there, even if it's in an accent or it's written in a way that you wouldn't necessarily say. Just try it and hear what it sounds like coming from your mouth, and I think I had fun with that.

There are [other] characters in the book, so it's not all Michael who's close to me. I narrate also his Jamaican grandmother and his Greek Cypriot relatives as well. And so I have to do a bit of a patois and I have to do some actual Greek. That was really fun for me as well, because I'm not comfortable with either actually. I understand them and I was able to write them, but I don't actually speak to my Jamaican family in patois and I don't actually speak very much Greek to my Greek family, even though I am starting to learn the language, so it was quite a challenge for me to do both of those things, but I really enjoyed doing it.

AW: And you did it beautifully. It's just spot-on and I cannot imagine anyone else performing this.

DA: I've seen videos of people performing my poems now. It's quite funny. It's quite strange and surreal to hear someone read out your own writing, but good for them.

AW: I've heard authors say, "I create the work and I put it out in the world and it's no longer mine." So it's the extension of that where they're owning it.

DA: I don't know how I'd have felt if they got an actor or someone else to record the audiobook there. I might have been a bit hurt.

AW: I doubt that they were looking seriously ever at anyone else.

DA: I want to record some other people's audiobooks now. It's quite fun. It's lovely being in the studio. You have a director, you have a studio technician, and it's really good fun. You just get to live inside a book. You get to become the book. It's so cool.

AW: I love that. That was going to be one of my questions, whether you enjoyed this enough to now make it a part of your repertoire.

DA: If they'll have me, I'm up for it. Any verse novel you want me to narrate, I'm there.

AW: I’m going to pull this out. You, Elizabeth Acevedo, you guys have got me pulled in.

DA: Elizabeth was an inspiration. The Poet X is one of the books that really gave me a template of how to write an excellent verse novel and I got to do some events with her when she came to the UK last year. It was just amazing to be onstage with her, to be on a book signing with her and to hang out in a green room with her and just chat…

AW: You also mentioned that Maya Angelou, I've read, is one of your inspirations, your author inspirations, because of a certain universality of her writing as well. Could you talk a little bit about that and how that translates into your current work?

DA: Maya Angelou always managed to speak to a moment and yet it remains so ever-present, what she has to say about Black people, Black women, and those who are oppressed or underestimated in society. I think of Still I Rise in particular. There are so many of us that can relate to that regardless of our specific identities. It's a really tough thing to do because there's a simplicity to her language, but there's also this boldness and this kind of defiance in what she's saying, and it cannot be underestimated how powerful those words are. It's funny, especially when you see her perform those words, but also when other people perform those words, you can see they're taking a bit of her magnitude, because she was just such a huge figure in so many ways. Even when you see her in her wheelchair, you know how huge she was and how much she had fought in her life and what she represented for so many people and continues to.

If poetry and a poet can do that much in the world, it's something that I want to aspire to. I think having a role model like that is big shoes to fill. I'm not trying to fill those shoes, but just seeing what's possible with poetry, straightforward, "I'm going to talk about my experience. I'm going to talk about our experience and I'm going to represent us the best way I can," and that she's done. We're so proud of her. Right?

I feel so well-represented and I can imagine as a Black woman in America that must be 10 times more for you. So I'm just thinking about that, and I guess I'm trying to do my bit in that regard for Black queer kids, wherever they are. I started with Britain now, but I'm coming to America and who knows where we'll go next?

AW: World takeover, Dean. I like it.

DA: Yeah.

AW: To that end, there's so many parts in this book that I want to play and replay, but particularly the epilogue:

How to come out as gay: Don't. Don't come out unless you want to. Don't come out for anyone else's sake. Don't come out because you think society expects you to. Come out for yourself. Come out to yourself. Shout, sing it, softly stutter. Correct those who say they knew before you did. That's not how sexuality works. It's yours to define. Being effeminate doesn't make you gay. Being sensitive doesn't make you gay. Being gay makes you gay.

It's a credo now. I can see this becoming a manifesto, and I've seen it pop up in different places and referred to as that. What does that feel like for you in this moment to be setting out in your work to inspire young gay teens, Black gays, and Black queers across the board? How does it feel to have set up something that is going to be a credo?

DA: Well, I wrote that piece for myself first and foremost. I was reflecting on when I was 15 and did come out. It kind of just happened and then suddenly, you're out and you can't go back in. But then I realized that actually you can and things change. Identity is what you make of it really. There are some people that come out and go back in the closet and there are some people that never come out, live a happy life, and the people that need to know, know. I think there's no one right way to do it, and there's no wrong way to do it. I don't agree with outing other people. It's a personal choice and it has to be done when that person feels able and comfortable to do it. Maybe not comfortable because it's uncomfortable because society is deeply homophobic. So it's never really going to be comfortable. But I just think when you feel ready enough to do it, that's when you do it and you've got to feel safe.

There are so many young people I speak to that ask me, "When should I come out?" I either refer them to that poem or say, "You've got to feel safe. You've got to maybe start with a friend or that family member that you can truly trust, but you don't have to come out to everyone straight away." That's what that poem is trying to say…

AW: That's really good. Does this mean that you'll be doing more novels? Where do you see this leading you to next?

DA: Definitely more novels. I had such a great experience with it. I'm loving storytelling. I'm loving character and world-building. I'm going to go a bit further from my own direct lived experience next time, I think, and write some different characters. That will be a real challenge for me because there are questions over who should write what identities, but I mean, if you do it with research and with care, then I don't think you can go too wrong. But also if you get it wrong, you take the criticism, you learn from it. You apologize if you need to...

AW: Any particular genres calling to you? Is there a sci-fi novel in you? What are we talking about?

DA: Witchcraft is getting me interested at the moment. I've got a sister who's really into crystals and potions and I've got another friend who's a shaman and I'm really interested in that kind of stuff. Someone who writes witches has let us down, so I think I need to step into the genre of magic and make it really queer.

AW: Amazing. Amazing. Have you started on a second book?

DA: I've started on three ideas. They’re with my agent and editors and we're thinking about which one to pursue. It's interesting because we're going to have to look at right now. What do people want to read in a year's time? Life has been really changed for so many of us. Do we want to read for escapism or do we want to see this current reality reflected in our literature? Do we want to write to before all this happened or do we want to write another possibility for the future?

A lot of authors that I talk to are grappling with this. Some people are shelving ideas. Some people are coming up with new ideas. Some people are forging ahead with the ideas they already had. But all of us are going to have to incorporate these new experiences that we're having in this shift in our societies, whether that's to do with the coronavirus, whether it's to do with Black Lives Matter, or whether it's to do with the environment and climate change. There's so much for us to grapple with, and whether or not it's in your literature, it's still a statement whether you exclude it or include it. You are making some sort of political statement there, so I am thinking about those things for myself, and I imagine most authors are.

AW: Dean, I'm so glad we got to talk today and I cannot wait for more people to listen to The Black Flamingo. It's wonderful.

DA: Thank you so much. It was a pleasure to chat to you.