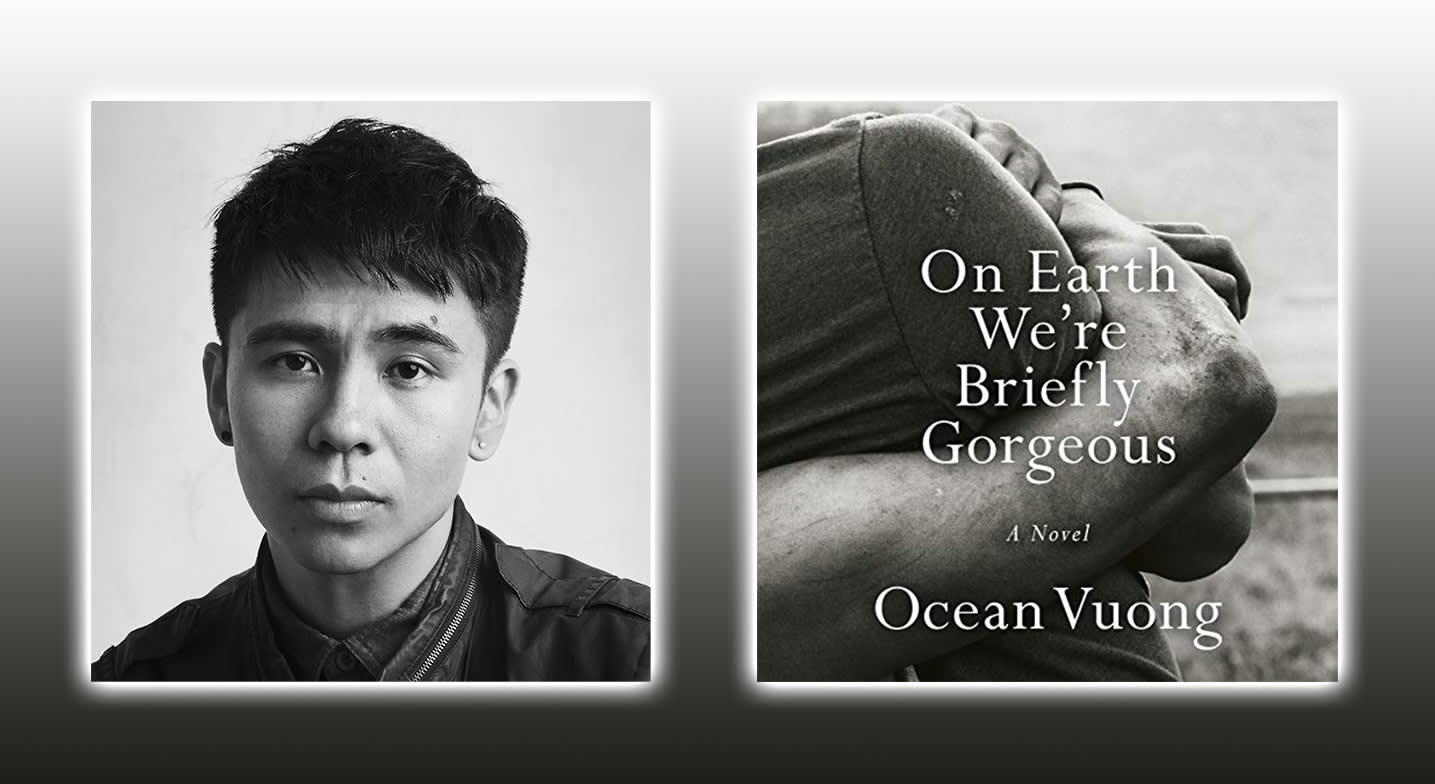

There is something so hauntingly beautiful about the way a skilled poet can spin a web of complex emotions thanks to a mastery of language that moves the rest of us to tears while it expertly drives home a point. Ocean Vuoing is that kind of poet, as seen in his critically acclaimed poetry collection, Night Sky with Exit Wounds. And he's now showing how deftly he can write at that level no matter the genre, with his stunning debut novel On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous, which he also narrates.

Editor Aaron Schwartz had the pleasure of attending an MFA program talk Vuong gave earlier this year and jumped at the chance to talk with him about what makes this novel so special. Listen in as they cover so much ground and Ocean drops one beautiful phrase after another.

Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

Aaron Schwartz: Hi, I'm Audible editor Aaron Schwartz, and I'm talking today with award-winning poet, and now novelist, Ocean Vuong. His new book, On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous, is his debut novel--a story told from the perspective of a son, a character we know only as Little Dog, in the form of a letter to his illiterate mother. It's a heartbreaking and deeply moving story that hits on so many deep and complex themes, which we'll talk about today. Welcome, Ocean, and thanks for taking the time to talk.

Ocean Vuong: Of course. Thank you, Aaron. Glad to be here.

AS: So you're known for your incredible poetry, especially the critically acclaimed collection Night Sky With Exit Wounds, which won the T.S. Elliot Prize and the Whiting Award, and was named a New York Times Top 10 Book of 2016. Just to name a few of the accolades you've received.

On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous is your first novel, and a whole new kind of work for you. This novel deals with themes like masculine identity, sexual identity, family, war, violence, drug use--there's a lot. As a reader of your poetry, I know these are things you've been interested in exploring in that form as well. So, I'm curious... Why the novel? And how did this project take shape as a letter from Little Dog to his mother?

OV: I never planned on writing a novel. It's hard enough to do one genre. And I always thought to myself, "A novel? I'll wait for the next life to tackle that." But what happened... [When] you write a book of poems, you never expect it to do what Night Sky did. And I'm still just following that book. I'm the shadow of that book in a way. I'm just catching up to it. It has its own life in the world, which I'm very fortunate and grateful for.

What happens, however, when a book gains that kind of traction is that very quickly, the writer confronts this capitalistic anxiety. What now? What next? And all my friends and colleagues and editors are knocking and say, "Well, you wrote about geopolitical violence and how that informs American identity in relation to the intersections of poverty, masculinity, and queerness. Now what? What are you going to do for the second book of poems?" As if now I have to write about Mars or what have you.

And I think that's something that we have a lot of anxiety about as a country, particularly in relation to creators. Whether it's poems, or TV shows, or even products, food, recipes, we have to constantly reinvent ourselves, or else we're static. And to be static is akin to death, creative death.

But I always felt that the questions that I asked in Night Sky were inexhaustible to me. That there's no way an 85-page paperback of poetry can possibly be an ultimate container for such large questions I've been asking my whole life. And so, we hear often about the sophomore slump, and I think there is something to it in the sense that a writer is now almost sometimes demanded to reinvent herself after spending her whole life writing one thing, or negotiating one theme. And so, after the first book, in a span of four or five years, we're asked to do something [different], present a fresh new flavor.

I would encourage every writer attempting a novel to take a serious earnest attempt at writing poems ...you have to pay attention even to the line, even to every syntactic unit, every breath. It creates hypervigilance to the torque and sensibilities of a certain sentence.

I was really depressed. I thought, all of a sudden, you get your dream, which is to write a book people care about. Then, all of a sudden, it's about cranking them out. And I never saw myself as having a career as a writer, and I still don't. It sounds bizarre because that's everything I do now. But I don't think writing is a career. I think a book is a singular act. I happened to have two, so far. That might be it. And if that's the case, that's a good life. That's a good creative life. Some people don't get to do even one. So I treat them as singular acts, singular epicenters.

And so, the novel was a way to delay or detour from that expectation, and to take the questions that I always felt were potent into a different form and see if I would surprise myself. And so, it was an experiment. It was a secret experiment that I did. I didn't show my agent anything until the fourth draft.

AS: Oh really?

OV: Yes, I went through everything. I have to know where this bridge is going, Aaron, because often my bridges go nowhere. So, before I invite folks on it, I've got to make sure it arrives at a destination. And so, that's how that came about. It was taking the questions from the poems, and with the faith that they are inexhaustible questions.

AS: That point you brought up about the books, and how lucky you've been to have them exist, it reminded me that at the reading I got to see you do this past fall, in the Q & A, I remember somebody asking you something along the lines of, how do you know if your work is done? And you said something like that it's never really done. And then even though the book exists, I believe you said, you still rewrite some of those poems.

I talked about that afterwards with some of my fellow students who were with me at that reading, and we thought that was so interesting.

OV: Yes, absolutely. I mean the book is a fossil. As soon as you write it, as soon as it's published, it's locked in time. It's locked in time and space, like a photograph is. Of course, you look at a photograph of yourself taken even last year, and yourself, your biology, your physical self changes as soon as that photograph is taken. And so why shouldn't something as organic and lively as a creative text also continue to grow. And it's just a negotiation we make according to the limitations of publication.

But I don't think a work is ever finished. We simply let it go, or we let it go to be fossilized. But I think we still obsess over it. We still tend to it. And this is how our ancestors, by the way, created for most of our species. Now we have to understand writing and publishing is still new in relation to our species. Homer's The Odyssey was memorized by the Greeks in its entirety. And of course, somebody went in there and made some changes, and memorized differently, and added their own flavor to it. That's why I think Wikipedia is one of the most faithful mediums of our species' inquiry. Self-inquiry.

AS: I agree.

OV: Is that we're always updating ourselves. And so, even as the book is published in the world, my brain has already updated it to something else.

AS: Yeah. That's incredible. So, has that happened with this novel yet?

OV: Not yet. Because I haven't read it. I'm sure once I'm on the road, I start reading it, I'll have to stop in the middle and take out the pen, and make some marks as we go. I dread that, but it's going to happen. I know it.

The ear is such a good editor when it comes to rhythm, pressure, momentum.

AS: I found that after having heard you read your poetry, and then actually having read your poetry myself, and then reading and listening to this novel, it's still so poetic. And the language is just so beautiful. And I wonder in writing and in revising the novel, how important was it for you to maintain the power and elegance of your kind of poetic writing in this prose?

OV: It became the only way I knew how to write. And I think, I would encourage every writer attempting a novel to take a serious earnest attempt at writing poems because the poem has a contracted stage called the line break. And so, in prose we often think of sentence, perhaps on the most minute level, and then paragraphs. But in poetry, you have to pay attention even to the line, even to every syntactic unit, every breath. It creates hypervigilance to the torque and sensibilities of a certain sentence.

And what happens is that you look at sentence making differently. You break them apart. Literally, the line break is a fracture of the sentence. And they become these sort of crystalline objects. And I thought, that would be one of the greatest advantages in prose is to take that same care and use the propulsion of the paragraph to move it forward.

And I think some of my favorite novelists were hardcore poets. We think of Moby Dick and Herman Melville. Fun fact, Melville wrote more lines of poetry than Emily Dickinsonand Walt Whitman combined.

AS: Really?

OV: Absolutely. Especially after Moby Dick. And I think for a lot of American letters, folks worked between those genres quite fluidly. We think of Faulkner. Faulkner called himself a failed poet, and that's being hard on himself. He wrote two volumes before his first novel. We think of Raymond Carver, Denis Johnson, Joyce Carol Oates, Annie Dillard, even James Baldwin had his hand. And so I think to write poetry is to care on the level of the atom for language, and anyone who is trying to write a novel should be an apprentice of the sentence. And to be an apprentice of the sentence is to write poems.

AS: I like that. The apprentice of a sentence. I like that. So, you're very familiar with reading your poetry out loud. That's what poetry is made for, is to read it out loud. And what I loved about listening to this audio book, and listening to you read your poetry is that you have such a command of the language, and your presence in reading is really transfixing. And so, I'm wondering what reading the audio book and narrating the audio book, is how different or similar that was from you reading your poetry.

OV: It was not that different because when I'm writing, I'm always writing aloud. Sometimes a line, or a sentence, or a paragraph would come on a walk. And I would just mumble it over and over, just to get the syntax right, just to get where the subordinate clause is, where the independent clauses come. And so, I think sometimes writing for me begins in the mouth. And that is, again, that's common. That's a very common thing in our species. We invented, and the oral tradition was part of the narrative structure. And so, it came quite natural to me.

There were challenges. I learned that I couldn't say certain words. It was very difficult to say the word "duh." I tripped up on that often. But it was a wonderful experience, and I didn't see much difference in it because I wrote this whole novel aloud. I would write a draft, and right away I would read it aloud. Read to others. The ear is such a good editor when it comes to rhythm, pressure, momentum. And reading it aloud, it gives your brain another auditory angle at the page, and that could only benefit the writing.

AS: Yeah. That's funny you mentioned that because my workshop professor -- I just had Julie Orringer -- she encouraged us to read the story out loud before you submit it to everybody because you'll find that there are so many things that you're not picking up on when you're not saying them.

OV: Right. Absolutely.

AS: Something that really struck me about this novel, among the many things, is something that I personally have been thinking about a lot myself in my own writing. And it's the idea of inherited trauma, and how there's this weight that we're predisposed to carry around with us in our lives that's kind of already been decided for us long before we're alive, or have any agency ourselves. And I'm amazed at how well you illustrate that through Little Dog. And I'm wondering, does that ring true to you, and was that something specific that you wanted to tackle in approaching this project, or did that kind of just come about as you were finding it on the page, or as the story just went on?

OV: Epigenetic trauma is interesting. Science is finally starting to consider it, starting to see its validity, but our ancestors knew. It's woven into our stories. It's woven into our folklore, our mythologies. Just this notion that the body remembers, and it can remember and recall and pass information down through the DNA, through the mitochondria. And so this is something that we've all understood as a species, but to write about it, to orchestrate it with language was a challenge, but also a pleasure.

And what I discovered in the process is that often when we think of trauma, we think of PTSD, we think of this burden that we inherit from our elders, and then even pass on to our children. But I also think that there's also a possibility simultaneously of instead of epigenetic trauma, but also epigenetic strength. And I think sometimes the trauma we feel, the PTSD that we experience are often tools, methods towards survival. And, oftentimes we are better suited for traumatic situations, right?

And so, what does trauma do? It creates vigilance, which we can call paranoia. And so, it creates this mode of strength at times. And I think that's what Little Dog starts to understand, that yes, his family has a lot of mental illness because of the war. But they also taught him how to look at the world at its most minute detail in order to survive it. They taught him how to observe his surroundings. They taught him how to gain power through silence and observation.

And so, there's a moment in the book where he meditates on the fact of being visible is the first tenant to being hunted. So how do we both be gorgeous and visible, but also the visibility makes us prone to being hunted and being in danger. And I think that's why he finds such kinship with animals. And the book really explores the vulnerabilities, the strengths, and the possibilities of animals, and what we do to animals. And, of course, it's no accident that his name is Little Dog.

AS: Right. You brought up a vulnerability, and that was another thing I wanted to ask you about. Your writing is just so vulnerable and honest about so many things. But one thing in particular is masculinity, and about how the people and things around us push us as men to be or act a certain way. And I think we're in a time right now in our society where it's really important that we have male artists and voices like yours to explore the effects of that. So what kind of role do you think literature can play in helping make this much needed shift in how we treat boys and men in our society? Which in turn, how they treat others as well?

OV: The great potential of literature is right there in the page, language. I think to change masculinity, and I mean change, I don't mean do away. I'm not invested or interested in canceling masculinity. Because it has its purpose. Masculinity is not tied to gender. It has a use. It even has use for queer folks, people in transition.

AS: Absolutely.

OV: But I'm interested in complicating it. I'm interested in expanding its possibility. Right now, it's a small monolith, if that even makes sense. It's a tiny monolith. It's sold to us. And what we call it, the official name is hegemonic masculinity, which ends up being the toxic masculinity that we feel. And when we look at it, we realize that it's actually a cage. It's not a liberating force that is often sold to us. It's not a means. It's not full of agency. It's actually incredibly restrictive.

Growing up in the early oughts, one of the status phrases I heard as a kid, as a boy growing up, was "no homo." Right. "No homo" was used within certain circles of boys and men as permission, as a spell, as abracadabra, for what? Touch. This basic human act to simply touch, which is proven to be a biological need amongst our species, can only happen through a magic spell called "no homo." So, when masculinity has gone to the point where it starts to deny our humanity, it has to be killing us. And that's what it has been doing. Not only us, but those around us. Right? Those within other genders and other sexes, and everything in between.

I'm interested in expanding it. I see American masculinity as something that has not yet had the opportunity to mature. There's much work to be done in it. Literature can simply complicate it, can simply chip away at the monolith through language. Language is very important because how masculinity becomes toxic begins with language.

If we think about how we celebrate our boys, and how men in this country celebrate each other, it is often through the lexicon of death and conquest. "You killed it, man." "You smashed her." "You went in there guns blazing, right?" "You owned it." "You owned that workshop." "You knocked it out." "You're killing the game." "You're making a killing." An audience is a "target audience." A state is a "battleground state."

These are all ways of seeing, and the saddest part for me as a writer and a negotiator of language is that these are all celebratory. We have chosen, and it is a choice, we have chosen in this country to celebrate our men through the lexicon of death. And it is no wonder that we arrive at an incredibly toxic space.

AS: I've never thought of it like that. That's crazy. This is a real switch of gears, but I was wondering if you are an audio book fan, and if so, what was the last great audio book that you listened to?

OV: I'm just starting into it because I'm a dedicated a reader.

AS: Sure.

OV: I need the tactile book. But I also love the oral tradition. And one of my favorites was actually a former Brooklyn college professor, Michael Cunningham.

AS: Oh, absolutely.

OV: I mean if you have a chance, listen to him read The Hours. It's one of those moments where, when a text gets published, it becomes in a way a civic document. Everyone can negotiate with it. Everyone can read it. But when you hear Michael Cunningham read The Hours, you realize that, only he could ever read it the way it should be. And I rarely say that. I believe that a text can be brought to life by anybody in very different ways. But when you read it, you say, oh my goodness, this is it. This is definitely his book. And he reads it the way it exists in your head so it's almost like listening to an echo. If you read the book before, and then you listen to audio book, it's almost like listening to an echo of the voice in your head when you first read it. And I highly recommend that one.

AS: I'll definitely check it out. And I want to say that going in between reading and listening to your novel, I feel the same way about how you performed narrating this book. It's so incredible. And I've been talking about it nonstop in the office.

OV: Oh, thank you, Aaron. Thank you. That's very kind of you.

AS: And it's been such a pleasure reading that and revisiting your poetry and listening to the audiobook. And I want to thank you for taking the time to talk because it's been really enlightening and I've had such a great time.

OV: Of course. Of course. Thank you. Thank you. And thank you for being a writer yourself, and congratulations on finishing your first year at the MFA. That's great to know.

AS: Thank you, Ocean. I appreciate that.