As the world gorges itself on wirelessly transmitted goodies — videos, games, audiobooks, podcasts, music, tweets, and texts — people are also demanding that their content be delivered at ever-greater speeds, to the point that some worryour current wireless bandwidth just can’t handle it all.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has been warning of a “spectrum crunch” since 2010, arguing that “demand for mobile broadband service is likely to outstrip spectrum capacity in the near-term.”

A crunch means more than just dropped calls and frozen videos. If mobile transmissions stop moving, emergency communications will fail, smart tech (i.e., mobile devices that can surf the internet) will be inoperable, and the whole economy — now inextricably tied to the wireless universe — will suffer as a result.

While some think that talk of a bandwidth crisis has been greatly exaggerated, the U.S. government has taken recent actions to try to ensure that there’s enough room to meet these exponential demands on what is a very finite broadcast spectrum.

Because the FCC has auctioned off most of the access to the spectrum, pretty much every bit of it is accounted for — with more gadgets accessing frequencies every day.

Along with the FCC, research heavyweights like the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the National Science Foundation have begun efforts to change the spectrum landscape either by opening up parts of the spectrum for high-speed mobile use, developing new ways to share the existing spectrum, or working to create the next generation of ultra-high-speed networks.

“Whatever your approach here, making more spectrum available to meet the demands of consumers and businesses in the United States is a national priority,” says Scott Bergmann, vice president of regulatory affairs at CTIA, a trade group for the wireless industry. “If we don’t have enough spectrum, we risk losing that global leadership and the innovation. If we don’t have enough spectrum, everyone loses.”

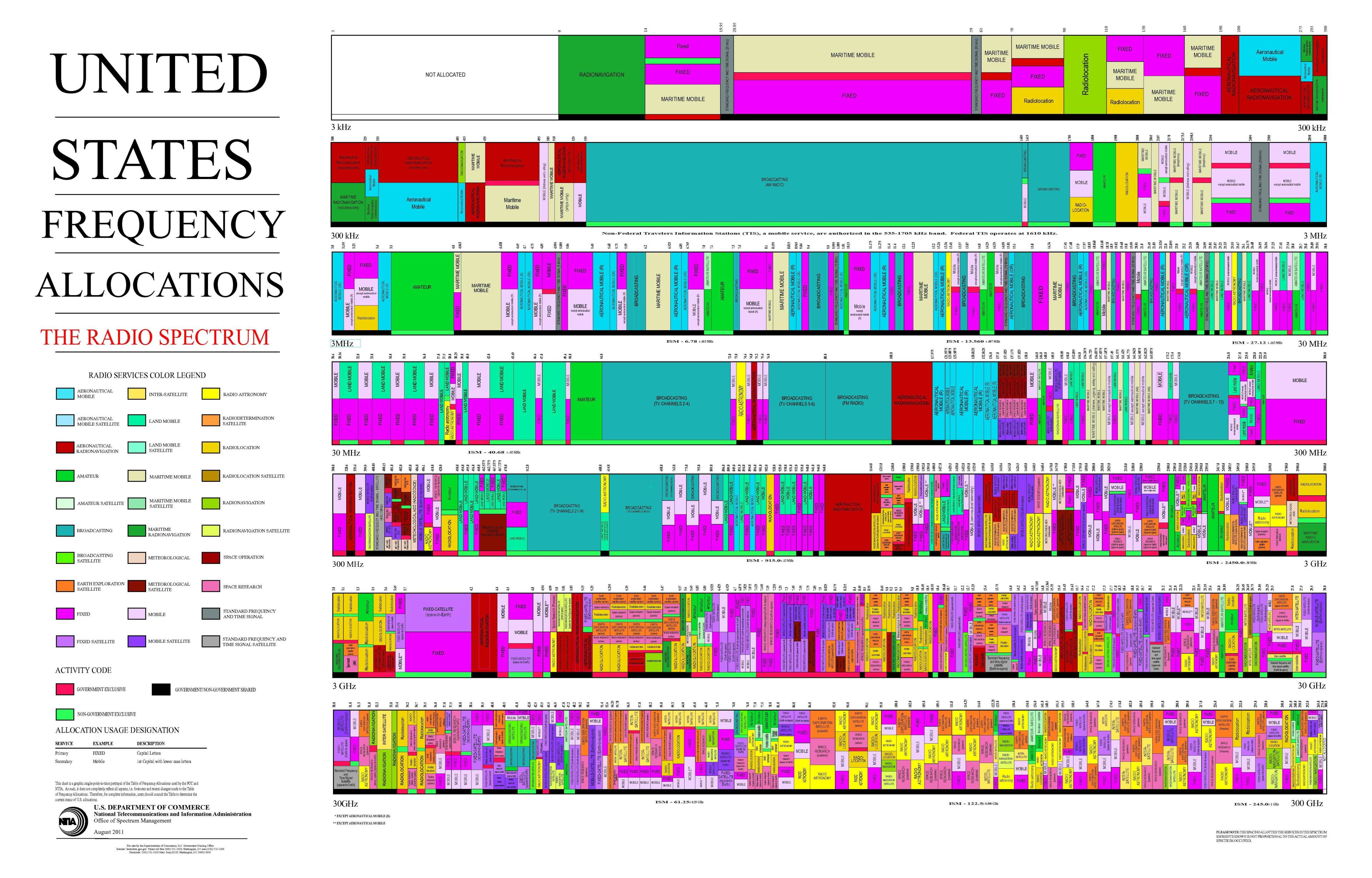

Technically speaking, the radio spectrum — the part of the electromagnetic spectrum that ranges from 3 Hz to 3,000 GHz — is the medium over which first broadcast and now wireless signals are delivered. A governing body, the International Telecommunication Union, has split up the spectrum into 12 parts, or bands, distinguished by frequency. Most television broadcasts and mobile-device data fall into the Ultra High Frequency (UHF) band, which spans 300 to 3,000 MHz. And because the FCC has auctioned off most of the access to the spectrum, pretty much every bit of it is accounted for — with more gadgets accessing frequencies every day.

To get an idea of demand, in 2014 mobile traffic was 14 times what it was in 2010, and by 2019, traffic demand will increase another six times, according to a CTIA report. Since 1994, the FCC has used auctions to sell access to portions of the UHF band (and other bands) to companies. In 2008, for instance, AT&T and Verizon paid nearly $20 billion for the 700 MHz frequency, which they used to help boost 4G performance.

This brings us to how spectrum access is distributed. Think of the available bandwidth as rooms in a very popular luxury hotel. The FCC owns the entire property and, every so often, it sets aside a small portion of rooms to sell to a wedding party. If those rooms go unused, the FCC can release them and sell them to other customers in need. There’s a finite number of rooms and the FCC only doles them out infrequently. The result: a lot of people who can’t book a room at this particular hotel.

To resolve this dilemma (and to pave the way for increased wireless usage across the board), the FCC in 2010 put together a National Broadband Plan that recommended making additional spectrums — up to 500 MHz — available for wireless by 2020, including 300 MHz for mobile. This plan was a comprehensive approach to mitigating the overcrowding issue, but some critics said it isn’t really a long-term solution.

That’s where DARPA, the Pentagon’s research and development wing, comes in. Earlier this year, the organization announced the Spectrum Collaboration Challenge, a public call for strategies and suggestions to revolutionize the way devices work together to access the broadcast spectrum. On the one hand, the program’s very existence gives validity to DARPA’s official stance: Spectrum overcrowding must be fixed. Behind the scenes, however, some DARPA staffers say the program actually proves there’s no crisis at all and that it is merely paving the way for a new era in spectrum management.

Take Paul Tilghman, program manager of DARPA’s Microsystems Technology Office. Tilghman says that while allocation is almost maxed out, utilization doesn’t even come close to maximum capacity.

While allocation is almost maxed out, utilization doesn’t even come close to maximum capacity.

“We’ve taken spectrum resource and we’ve rationed it and broken it up into little pieces and handed it out to network operators and told them to go forth and use it,” says Tilghman. “The problem with that is for every second or millisecond that the spectrum is not being used, there’s a potential chance to reuse that spectrum.” He adds, “There’s definitely more space to go around.”

One of DARPA’s potential solutions: spectrum sharing. The way Tilghman sees it, wireless entities would continue to purchase portions of the spectrum as they do today, but during off-peak periods in high-traffic areas, available spectrum could be reassigned to other areas that need it more. (Sticking with the hotel analogy, this would be like a hotel embracing dynamic pricing to offer discount rooms in periods of low demand.)

Tilghman isn’t the only supporter of spectrum sharing. In London, where a large amount of research is being done on the problem of broadcast-spectrum overcrowding, H Sama Nwana sees sharing as a viable solution too. Nwana is the executive director of the Dynamic Spectrum Alliance (DSA) and has spoken out vociferously in favor of spectrum sharing as the best fix for the purported overcrowding crisis.

“Sharing the spectrum gives everyone what they want and does not require anybody to reinvent the industry.”

“Most spectrum is not being used in most of the places most of the time,” he explains, citing Singapore as a perfect example because the nation has almost 100 percent allocation (all of the hotel rooms are reserved) but only 6.5 percent utilization (the vast majority of rooms aren’t actually slept in). “In America, for instance, 72 percent of [Americans] live on the coasts or around the Gulf of Mexico and, outside of those three areas, most of the spectrum is completely unused.”

The way Nwana sees it, one key to spectrum sharing is to open more bands so that different kinds of traffic — both licensed (paid for) and unlicensed (free and open to all) — can be sent at higher frequencies, thereby improving transmission speeds across the board.

In particular, the DSA is in favor of expanding the portions of the broadband spectrum available for unlicensed operations. Nwana notes that another key to spectrum sharing would be to prioritize different kinds of signals so that government and emergency-response organizations get priority.

“The way I see it, the solution for solving the perceived spectrum crisis is right in front of us,” he says. “Instead of spending inordinate amounts of time and money on creating something new, sharing the spectrum gives everyone what they want and does not require anybody to reinvent the industry.”

But spectrum sharing still has its skeptics. Internet access providers — companies that have purchased (through auction, of course) pieces of the spectrum for exclusive and licensed use — might have to rethink their profit models if they have to share the spectrum. And government entities — particularly the military — aren’t necessarily jumping at the chance to give up some of their spectrum slices.

In March, Defense Department CIO Terry Halvorsen told the House Armed Services subcommittee that private companies seeking more bandwidth could put military operations at risk. “What I worry about is that the private-sector demand will exceed our ability to keep pace and that we could, if we’re not careful, put some national systems at risk,” he said. “In this business, I get that time is valuable, but there is a physical limitation to how fast we can move DOD systems … to share spectrum or get out of some spectrum.”

Whatever happens with regard to sharing, everybody in the telecom industry is gearing up for the push to 5G, the next phase in telecom standards that promises to deliver data more quickly and more reliably.

In July, the FCC unanimously designated a large block of spectrum for next-generation wireless broadband services as well as fixed networks that could supplant current wired broadband. The new section of spectrum is in higher bands than those used currently (including 28 GHz, 37 GHz, and 39 GHz) and can deliver data faster than current networks. These new 5G services could provide improved speeds up to 100 times faster than those delivered by today’s 4G wireless networks. They are expected to come online by 2020.

That same month, the White House announced that the National Science Foundation would be leading a $400 million research effort to create the next generation of wireless networks “for 5G and beyond” that could usher in the age of five-second movie downloads, real-time medical data from emergency responders, and driverless cars.

Few would dispute these developments are good news. Still, there are challenges inherent in the expansion.

For starters, the 5G spectrum is not well defined just yet, and it very easily could be earmarked for different kinds of traffic (say, government use in a national security emergency) than the bulk of consumer traffic today. Tilghman also questions the strategy behind 5G, noting that it will be the first time in history that the nation has designed the primary commercial wireless standard without a single goal in mind.

CTIA’s Bergmann says another challenge will be to continue to free up enough spectrum to keep up with consumer demand, especially as the so-called Internet of Things (IoT) takes off. (Think intelligent home heating and cooling systems, for example.) In particular, he cites CTIA’s estimate that the IoT will add $2.7 trillion to the economy over the next 15 years and that as many as 200 million connected automobiles are expected to hit the world’s roadways by 2020, creating an unprecedented amount of data demand.

And that means a fully booked spectrum is just not an option.

“The more reliant we become on sharing information over the spectrum, the more difficult solving this problem becomes,” says Bergmann. “This isn’t a problem that’s going away. We can and will figure it out together.”