Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

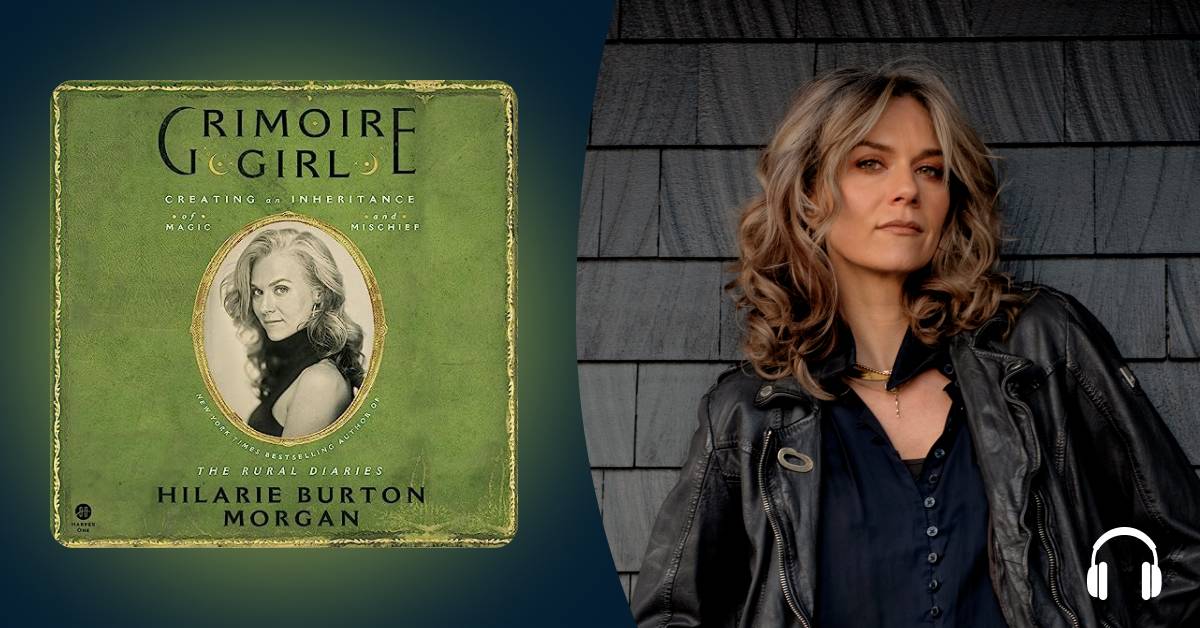

Alanna McAuliffe: Hi there, listeners. I'm Audible Editor Alanna McAuliffe, and today I have the distinct pleasure of speaking with actor, writer, and creative Hilarie Burton Morgan on her enchanting new memoir, Grimoire Girl. Hilarie is perhaps best known for her breakout role as Peyton Sawyer on One Tree Hill, an emotionally complex teen character that deeply resonated with me as an angsty emo music loving young adult. But since her teen days, Hilarie has become the definition of a multi-hyphenate.

She starred on multiple shows including White Collar and Grey's Anatomy, settled in with her family on Mischief Farm in Upstate New York, penned two memoirs, started a liquor line with her husband, bought a local candy shop, and has proven herself to be a fierce advocate for social justice. And now, she's added magical mentor to that long running resume too. Hilarie, I am so glad to be sharing this space with you. Thank you so much for being here.

Hilarie Burton Morgan: That was the nicest intro I've ever heard. (laughs)

AM: Oh, of course. Well, I'm just so happy to be sitting down and talking with you today.

HBM: Thanks.

AM: To get started, I wanted to ask you a bit about the format of your latest audiobook. It's arranged as a series of personal anecdotes and recollections interwoven with guidance on how listeners can begin to incorporate simple spell work into their own day-to-day. Why did the format of a Grimoire speak to you? And what ultimately inspired you to encourage others in this pursuit of survival and self-discovery?

HBM: Well, the organization of this book was definitely the hardest task. Writing each chapter was so easy. I could write a chapter in like two hours, be really pleased with it. But the organization was difficult, because I essentially was taking journals that I'd kept from the time I was a teenager and smashing them all together and taking the most important bits out of each one. And so, I had my marble composition notes from high school, where I had really, really awful poetry and a lot of big questions that you write down when you're a teenager. I was a very religious kid—I went to church multiple times a week and had very big questions about how I could reconcile the church that I was growing up in with the theater world that I was involved in and what my innate sense of right and wrong was and where that conflict was.

Then I get to college, and, of course, I start taking theology classes and criminology classes and writing classes and art of the novel and all of those things. And I had just so many notebooks in my attic to sift through. And then I had a separate storage area down in the basement for all my One Tree Hill years, where I wrote about the ghost that lived in my house. And I started really delving into a lot of magical thinking and the history of witchcraft, or just the history of women in general.

And so, taking all of those different chunks of my life and putting them together in a narrative that had flow to it and could move from my childhood home to my young adulthood to my current home was really hard. (laughs) It was really hard.

AM: I can imagine, yeah.

HBM: Yeah.

AM: That's quite the undertaking.

HBM: It's like taking hoarding and trying to make it palatable for a mass audience.

AM: It's hoarding as an art form.

HBM: Sure, sure, sure. Yeah, we all have different hobbies. Mine's hoarding notebooks.

AM: (laughs)

HBM: But I split it up into three sections, and each section is representative of a different home that has imprinted on me. So, there is the first section which heavily deals with my home back in Sterling Park, Virginia, growing up at the base of the Blue Ridge Mountains and what that meant, you know, what that folklore was and how it sent me off into the world. And then, the second chunk is all about my One Tree Hill years and early adulthood living in a very, very haunted house.

And then I get up into my current home, which is the Hudson Valley where there really is a lot of mysticism here. I mean, John Irving made a living out of writing scary stories about the Hudson Valley. So, it feels good to land here.

AM: Absolutely. Yeah. That definitely makes sense. And I will say I visited Rhinebeck, New York, where you now reside with your family.

HBM: Oh, right on.

AM: It's exactly what you said. There's an air of this almost otherworldly whimsy. And may I just add as a brief aside that Samuel's Sweet Shop is just a delight.

HBM: (laughs) Well, that was a great plug. I'm drinking Samuel's coffee right now.

AM: (laughs)

HBM: Ta da.

AM: I'm wondering, since you've lived so many different places and this idea of home has shifted so many times over the years for you, do you find that there is a different kind of magic in these smaller towns and communities as opposed to larger cities where you've lived? And if so, is that sense of magic inherent. or is it something that you've had to kind of find and cultivate along the way?

HBM: So, I would say duality is my favorite thing in life, right? And it was like when I was working on One Tree Hill, I was also working back in Manhattan at TRL, you know? Because I had duality. I had small town and the big city. And here, or when I was growing up in Virginia, I lived in this smaller town but had DC right there where I could go and do professional theater as a child.

Here in the Hudson Valley, we obviously live in a very small town—it’s like 9,000 people here—but we have Manhattan that's so close. And so that duality is really important. Because in bigger cities where you get to be anonymous in a way, the magic is in your anonymity, right? The magic is in your privacy.

AM: Mm-hmm.

HBM: It's being able to walk down the street and be a mystery to everyone around you. And that's really exciting. And I definitely think that's something that people should cultivate. Here in this small town—I watched the Barbie movie with my kids the other day. And the scene in Barbieland where everyone's like, "Hi, Barbie! Hi, Barbie! Hi, Barbie! Hi, Barbie!”

AM: (laughs)

HBM: And everybody knows everybody—that is an example of how wonderful it is there because everyone knows everyone. And the magic is collective, right? That's what I experience living in this small town—collective magic, where we're celebrating all each other's wins. We are holding each other in each other's losses, you know?

AM: While we're on the topic of magic—it's something that came up a lot for me throughout the book, and I know that it's something you meditated on a lot too. Historically, there's been a lot of unease surrounding sort of perceived spiritual mysticism. Even today, despite this kind of growing fascination and comfort with things like witchcraft and spiritualism, that taboo still persists.

HBM: Sure.

AM: So, I'm wondering why you think that that suspicion persists even to this day? And whether or not you foresee a shift towards maybe a more open-minded approach to witchcraft, spiritualism, or mysticism in general?

HBM: Yeah. I mean, obviously we know from our history lessons that none of the people who were killed for being witches were—they weren't drinking off the teat of the devil, right? (laughs)

AM: (laughs)

HBM: It was misogyny. King James had horrible mommy issues.

AM: Mm-hmm.

HBM: So, he did two things in his legacy. He chased women for being witches and tortured them, and he wrote a Bible. And so, it's really complicated to move forward with the Christianity that we've been presented knowing how deeply affected it's been by misogyny. The women who were persecuted were odd birds. They were outspoken. They owned land that someone else wanted. You know, we know all of this stuff. And what we're seeing today is a political backlash against women who are demanding their autonomy and their power and their place in this world.

"The women who were persecuted were odd birds. They were outspoken. They owned land that someone else wanted. You know, we know all of this stuff. And what we're seeing today is a political backlash against women who are demanding their autonomy and their power and their place in this world."

So, it's not a new story, you know? It's age-old. I think what we have on our side now is as much as everybody hates social media, God bless it, right?

AM: Yeah.

HBM: People who are in small towns need that lifeline. Me, growing up as a kid in small town, I didn't know who to ask these questions. I didn't know who to ask about all the women in the Bible, and why a lot of them were portrayed really terribly. I didn't know who to ask about pagan goddesses and Greek goddesses and to find power in those narratives.

Because it's not necessarily that you're worshiping those goddesses or gods—it’s that you're finding that collective similarity. Where, if the gods can go through heartbreak, If the gods can go through loss, it makes it more bearable for stupid humans to do it too.

AM: And, ultimately, how inseparable love and grief are. And they're just these forces that, inevitably, as a fact of being human beings, we will encounter.

HBM: Mm-hmm.

AM: You wrote a particularly stirring passage about the passing of your dear friend, Markie, and how you commemorated her loss with roses similar to those that she grew herself. I thought that was so beautiful. So, because I feel like this is a safe space to get a little morbid, I was wondering if there are any things, be they of the natural world or human creation, that you hope would offer a tangible memory of yourself upon your passing for those you love.

HBM: Oh. Oh, wow. That's … hard. (laughs) What a good question. Geez.

Yeah, you know—that was the original intent of this book. I had read a book called Italian Folk Magic by Mary-Grace Fahrun. And she is a nurse in Canada with this strong Italian heritage. And she talked about how it was really her aunts and grandmothers that passed down this mystical Italian thinking to her. And I don't have that—I don't have a relationship with grandparents; I don't have aunts and uncles. I don't have that. And it really upset me when I had my daughter, what am I going to give her, you know? Like, I don't have any stories. I don't have it, so I have to invent it and work on it. So that by the time I do go, it's like rich and weird. (laughs) And something that she gets to pick and choose from.

And so, that was the original intent of this book—to collect all the weird stuff that I have been accumulating over the years. I would say for my children, though, my biggest thing I want them to carry is a real sense of joy about stupid stuff, right?

AM: (laughs)

HBM: Because I grew up around some people that were dark about everything—they hated everyone. Everything was a burden, you know. And when you're a child growing up in that environment, you have to start doing magical thinking so that you don't fall into the black hole. So, I think a lot of the way I process trauma, and just deal with day-to-day stuff, is to make it a narrative and make it colorful. And so, sparing my children the trauma (laughs), I would still like them to be the kind of people that marvel at silly things.

And it's nice to see the sprinklings of that. Like, we have an old man that sits in our town by the stop sign by the elementary school. And he holds up a clipboard every morning with a different message for the kids. And my daughter lives for this. She's like, "Here he comes. What's he going to say today?"

AM: (laughs)

HBM: And it's something you could really easily pass by and not pay attention to. But I wanted to raise children that see magic in clipboards and in strangers and in the leaves falling. And yeah, they've really got a handle on mysticism at a young age. And so, I hope I've spared them trauma (laughs) and maintained that. I'm like, here's a shortcut to magical thinking—you’ll go to therapy for different things when you're a grownup!

"I think a lot of the way I process trauma, and just deal with day-to-day stuff, is to make it a narrative and make it colorful."

AM: (laughs)

HBM: (laughs)

AM: No, that's really gorgeous. I am tearing up right now at this image of this old man with the clipboard.

HBM: Oh my God. Babe, listen, at first I really had to ask around. And I was like, "Do we know this guy? He's cool? He's cool here?" And a couple of other parents were like, “Yes, he goes to the church on the corner, and he announced at the beginning of the year that he just really wanted to cheer for the kids this year.” And like, what a lovely thing. And what a lovely thing for the children to notice, you know?

AM: Yeah.

HBM: It's really easy to be zeroed into your phone or your iPad or just like, you know, thinking about yourself. And so, to be looking up and looking around, that's what I want to give my kids.

AM: Yeah. I mean, I don't think you could leave them with anything better than that. It's so easy to fall into the cynicism trap.

HBM: Mm.

AM: But hope and joy are all we have at the end of the day. I think that's such, just a purely lovely thing to leave behind on this Earth—just live as kindly as you can and as gently as you can. So that's beautiful, really.

HBM: Thank you.

AM: And I guess, you know, since I've gotten the ball rolling on the topic of death …

HBM: Look, I played Peyton Sawyer, and I remember everyone telling me how morbid I was. And I was like, "Yeah, you think so?" And now that I'm doing a podcast about the show, and I'm going back and I'm watching it, I'm seeing it as an adult looking at a child. But I'm also thinking about all the deaths that happened when I was a teenage that really like colored Peyton and therefore have colored me.

It feels strange to be the death lady, but it is a mantle that I'm proud to carry. (laughs) If we can embrace death and like be cool about it, cool.

AM: I think the more we talk about taboo subjects, be they witchcraft or death, it’s opening up conversations that we need to be having.

HBM: Right. Like, make sure you tell the people that you're going to haunt that you're going to haunt them, so they know—so they're looking out.

AM: (laughs) Well, since I cannot resist an invitation to talk about haunts … One of my favorite stories in Grimoire Girl recalled your experience living in a haunted house in Wilmington, North Carolina, with your cantankerous spectral roommate, Hester.

HBM: Yeah.(laughs)

AM: I'm wondering if you've had any other ghostly encounters of note since then?

HBM: My very first ghost encounter ever was in Seaside Heights, New Jersey, when we were doing the MTV Beach House. We had to stay in this Victorian house. And I for sure thought that somebody was screwing with me. Because I was like, “We're the only people staying here.” It was just the VJs staying in this Victorian house, and somebody's kid's running around all over the damn place and stomping around at 2:00 AM in the morning. It was crazy. I was mad because I had to get up. (laughs)

AM: (laughs)

HBM: And so, obviously, you do the thing—you go to the front desk and they're like, "Sorry, baby, there's no kids here." And then, the water would start doing weird stuff in the room. If I was watching kid-friendly shows, everything would be fine. I watched a lot of Nick at Night back in those days. Everything was fine. The second I would put in on like the news, all of the sudden the lights would flicker and the water in the bathtub would just turn on by itself. I mean, it was tricky.

So that was my first one. And that really made me swallow a lot of my own ego, because I had been hearing ghost stories from my father, who grew up in rural Virginia, my whole life. And I was always like, "Okay, cool story, Dad."

AM: (laughs)

HBM: And then when it happens to you, you really do feel insane. But when I lived on Nun Street in Wilmington, North Carolina, and I had Hester as my roommate, you know, it was seven years of constant activity that other people experienced too. And when you're validated in that way, it makes it so much easier to talk about. Because if something happens when you're by yourself, you feel like a freak. If something happens when you're with a group, you're like, okay, we can't all possibly be freaks.

I had an interesting experience the second I finished this book. And it had been kind of emotionally exhausting to really like finish, finish. Because I'm talking about the loss of a number of my dear friends. I'm talking about trauma in my own life. You know, it felt like going to a funeral, doing that final pass.

And so, I get home and I go to the bookstore. And I'm trying to get a book for a girlfriend of mine. And this one book keeps falling off the shelf, over and over and over again. And I cannot, for the life of me, get this book to stay on the shelf. And so, finally I pick it up. This was at Oblong Books here in Rhinebeck, and it was called The Haunting of Alma Fielding. It's about a woman who was possessed and spiritualists came and they were studying here. And there was a large conversation as to what was real about the paranormal stuff that was happening with her, and what was induced by the trauma that she'd experienced. Because they say that when you are in a traumatic state, you are more open to this kind of activity.

And so, I'm looking at the book and I'm like, “Fine, I'll buy it. Fine.” And I read the prologue. And right there in the prologue, they're talking about a Greek myth with Amphisbaena. And I was like, “What is that?” It describes it as the spawn of blood dripped from Medusa's head, and it forms a two-headed snake. And I had just finished writing about the two-headed snake I had tattooed on my hip in Portland with the name of my childhood street, Ithaca, in the middle of it. And this book really wanted me to buy it so bad. And I had never studied the correlation between haunting and trauma before.

AM: Mm-hmm.

HBM: But as I wrote about this haunting I’d experienced on One Tree Hill—which now, as I have been able to share, was a very traumatic experience—all of the sudden all these puzzle pieces came together. (laughs) And I was like, “Okay, well, someone wanted me to read this book!” Someone wanted me to have that two-headed snake imagery and to know what it was called. And to understand what that chapter of my life was.

So, yeah. I love when weird, weird stuff like that happens, because I don't need to explain it. I just like to believe that something wanted me to read The Haunting of Alma Field. (laughs)

AM: Oh, that's incredible. Some things we don't need a concrete or scientific reason for.

HBM: Well, there's a narcissism to wanting everything explained.

AM: Mm-hmm.

HBM: Like you deserve the answers, right? I deserve to know that this is. I want all the answers. There's a humility in acknowledging and being happy with the idea that you don't need to know everything.

AM: Right.

HBM: There's magic in the world. I always said it was, like, God has such a better imagination than man, you know what I mean?

AM: (laughs) Yeah.

HBM: Man's not going to know everything that was dreamed of.

AM: Absolutely.

HBM: It's way more fun to think that bigfoot and fairies and all that stuff is real. (laughs) My husband gets so frustrated. I believe in everything. Once you live in a haunted house, you're like, “Who knows, man? Game on.”

AM: Yeah.

Listens that inspired Hillarie Burton Morgan:

HBM: It's all real.

AM: I'm honestly proud of myself that I have not monopolized this conversation talking about Mothman ad nauseam.

HBM: Oh, babe.

AM: (laughs)

HBM: Have you gone? Have you gone to West Virginia?

AM: Not yet, but the Mothman Festival's on my proverbial bucket list. I’ve got to go.

HBM: Yeah, yeah. There's a lot of weirdies out there. And I love all of them.

AM: (laughs)

HBM: They're so fun. (laughs)

"It's way more fun to think that bigfoot and fairies and all that stuff is real...I believe in everything. Once you live in a haunted house, you're like, 'Who knows, man? Game on.'"

AM: To touch back on a point that you made in your previous answer, I'm really struck by this description of the process of writing and recording your memoir as going to a funeral—which I completely understand, given a lot of the content, a lot of the traumas that you've lived through. But it also struck me because it reminded me of another note that you strike in your book, which is the idea of eulogizing

the self.

HBM: Mm.

AM: So I'm wondering, how is writing a memoir—or two, in your case—an application of the practice of self-eulogizing? Like, is it a similar process, or are they different beasts entirely?

HBM: When I'm writing, I am always conce

rned about the person reading. And maybe I shouldn't be, but I am—the same way with like when you're doing a performance. In any acting I've done, I'm very concerned about the woman at home who has lived the experience that I am pretending. And I've had a lot of women come up and say, "I've experienced domestic violence. I've experienced loss from breast cancer. I've experienced this thing. Thanks for playing it the way you played it." And there's just so much weight to that. It's like, “Don't fuck it up.” This is for someone else t

o interpret and use however they need it.

With your eulogy, with your own obituary that you work on throughout the course of your life, there's a little more naughtiness to that. I probably watched The Bridges of Madison County too young (laughs) because as a kid, this idea that these children really thought they had everything figured out about their mother, and they didn't know about this torrid affair that she'd had until she was dead and they found the artifacts up the attic—that really affected me.

And I was like, “Well, what stuff are my kids not going to know about me?” Because to them, I'm just the lady that picks them up and drops them off and cooks dinner. And I want to be wholesome for them. In their world, they're the main characters. They matter more. It's my job to make them the main characters. But when I die, I need to them know I was cool.

AM: (laughs)

HBM: And so, I started keeping this list forever ago of just all the cool stuff that I'd done that I knew I would forget about. Then as the years went on, it became a thing that I would go back to when I wasn't feeling so great about myself. When I was feeling insecure, when I was feeling rejected, I would go back, and I would look at this list and be like. “This is a wild mix of stuff that I've done in my life. I can probably do more.” So I think keeping that for yourself is a very important little secret to keep until you're ready to share it. And then let your kids read that over the dinner table when you're gone and just try to figure it, you know.

AM: You do keep some close to your c

hest, understandably, but you share quite a few doozies.

HBM: (laughs) There are definitely some I was like, “I'm not putting this one here. This one stays private.”

AM: (laughs) And you know what? I'm not g

oing to spoil any of them.

HBM: How nice.

AM: If anyone wants to hear them, they'll have to listen to your book.

HBM: Thanks.

AM: I'm so curious about this process of writing an

d recording a memoir. It's not your first time behind the microphone, certainly. You narrated your first memoir, The Rural Diaries. And you now cohost the absolutely delightful One Tree Hill rewatch podcast, Drama Queens, with your former costars Sophia Bush and Bethany Joy Lenz. In Grimoire Girl, you do talk about the emotional process of having recorded the latter. How does the experience of watching yourself on screen and reacting to it f

or a podcast differ?

HBM: Like I love writing. I love it. My greatest fear right now is putting out the next book, which will be fiction. And I have been writing fiction since I was in first grade. I mean, I still have books that I wrote in first grade because that'

s all I ever wanted to do. And acting was the thing that I did that made other people happy, you know? And so, I feel very fortunate that I've been able to do both to make other people ha

ppy and make myself happy in the trajectory of my professional career.

But I'm … nervous—I have stage fright about writing. And I don't have that about acting anymore. And so, I know where my heart is.

AM: Mm.

HBM: And so, it's nice to go back and watch the acting part of things, because I'm not envious of that anymore, you know? I think if I was still auditioning and wanting to carry a show and do all of that, it might be bittersweet to watch something that I did as a very, very young person. And think like, how do I recapture that magic? Being in this phase where I have all of these new hopes and dreams and aspirations, it allows me to isolate the acting part of my life in a way that is nurturing. I can be like, "Look at that little girl try so hard. She's trying, she's doing so good." I can separate myself from it. And I didn't anticipate how healing it would be to do that. Like I thought for sure, oh, this is going to be a hard watch. And there have been episodes that have been hard. But for the most part, I am able to see a kid that looks very much like my own children and feel a great deal of empathy for her. And pride in how hard she's working, and there's a sense of ac

complishment there that feels like good closure.

But yeah, I've said it in a number of interviews—I'm a deep introvert. (laughs) I like being by myself. I like hiding. And so, writing was always my dream job, and, thankfully, now I'm being mentored by really fabulous writers. Alice Hoffman is a mentor of mine. Angela Slatter, who is just a remarkable novelist and short story author down in Australia—she is a mentor of mine. And so, I've got these very accomplished women that are like, "Come on, you can do it." And that feels nice. That's the community I always wanted.

AM: For sure. And Alice Hoffman's also your pen pal, right?

HBM: Oh. I'm obsessed with her.

AM: (laughs).

HBM: Yeah. She and I, we became pen-pals back in 2019. We were supposed to go on like a lady date, a little friend date, because my husband was doing a movie in the Boston area. And this was February or March of 2020. She and I were supposed to meet on a Friday. And we both were like, "Hey, there's a lot of people around us like getting sick. Maybe we shouldn't go meet for lunch. Why don't we just like w

ait two weeks? We're not going anywhere. I'll see you in a couple weeks." And then by Tuesday, the whole world was shut down.

And so, I never got to go on that lady date with Alice Hoffman. But we have maintained this pen-pal relationship that is—it blows my mind every time I see her write my name. I'm like, "Oh my God. Not only does Alice Hoffman write my name, but she spells it right."

AM: (laughs)

HBM: Like, that's incredible! (laughs) She is so lovely. And I have really enjoyed reading all of her books, starting from her first book, Property Of, which is something she wrote as a very young woman about the girlfriends of gang members in like 1960s New York. I was like, "Alice, were you a bad girl?" And she's like, "Hilarie... maybe."

AM: (laughs)

HBM: I just love that book so much. I want to direct

it so bad. But now to her latest book, The Invisible Hour, which really marries her love of libraries—which is something we connect over—her love of, like, other authors. And just being able to process trauma by disappearing into a book. And I think that there's a legion of us that do that. And Alice is one; I am one. I think you're one. (laughs) You know?

AM: Absolutely.

HBM: But you can find each other in a crowd.

AM: For sure, yeah. While we're talking about storytelling a

nd books, there's this sentiment you express later in the book—you write, "The magic of storytelling is that each time we tell our story, it gets easier. We share more and ideas begin to crystallize as we say them out loud." And it's a line that especially struck me as this memoir, like The Rural Diaries, is author-narrated.

To what extent is your narrative process, or the art of spoken work in general, an act of manifesting magic? And is there any specific intention you’ve imbued your narration with?

HBM: Ooooh. My children make fun of this, that I

say things out loud, especially when we're driving around the village of Rhinebeck here, and I'm like, "A parking space will open up."

AM: (laughs)

HBM: And it always does, you guys. I don't want to brag about it, but they joke. They're like, "Oh geez, Mom," you know? I think saying things out loud is another one of those notions where this is a gift that we've been given, the gift to articulate and the gift to say things out loud and to communicate with each other. You're not just saying it for yourself. You're saying it to let other people know what your intentions are.

And so I say everything out loud, almost to a fault. And I've seen like memes, or I've seen like Instagram grid pictures where it's like, "Don't say what you're going do, just do it." And I say, bullshit, right? You say what you're going to do. And you say it, and you say it, and you say it, and you say it—and then it happens. And then you get to give yourself a little pat on the back. So for me, in writing this book, I really got to put to bed a lot of stuff that I had been struggling with. But I also got to finally be myself in a way that when you're so busy playing other characters, you have to be careful not to do. You know?

AM: Mm-hmm.

HBM: You kind of need to be beige to be an actor, because you need to fit into a lot of different places. And that's not my priority anymore. Now I'm just like a farmer and a PTSO mom. And so, I love being the witch PTSO mom in town. That's more fulfilling than anything else I've ever done.

So yeah, I think for me, putting it out into the world that I want to write fiction. I think crafting female narratives is really important—it's an act of therapy, but it's an act of community. And those are my goals in my 40s. So that's, you know, where we're headed.

"I think saying things out loud is another one of those notions where this is a gift that we've been given, the gift to articulate and the gift to say things out loud and to communicate with each other. You're not just saying it for yourself. You're saying it to let other people know what your intentions are."

AM: Absolutely. No, that definitely makes sense. And just to wrap it up, sadly, on that theme of storytelling, I was wondering if you had any audiobook or podcasts that you'd like to recommend to our listeners?

HBM: I'll tell you, the person who got me into podcasting is Aaron Mahnke, who hosts Lore. And he also produces Noble Blood that Dana Schwartz hosts. And he did one with Rabia Chaudry about the djinn. He is a lover of morbid history and gives book recommendations throughout the course of his podcast. I really appreciate Aaron because without even saying it out loud, he's able to tie the string from something wild that happened in the past to what's going on right now.

And so, for those little like 40-minute episodes, my son and I just listen to them back-to-back-to-back-to-back on car rides. And we marvel, you know. Sometimes the stories are awful. Sometimes they're magical. Sometimes they're so weird. Sometimes they're not appropriate.

AM: (laughs)

HBM: But I would say Aaron Mahnke's World of Lore has a little something for everyone. And when I was first dipping my toe in the podcast waters, Aaron came and sat with me and my family and taught me everything about the podcast industry. And I was actually supposed to be doing a podcast about witches with him. And that's when Drama Queens came around, and I had to go do Drama Queens. So one day, Aaron and I will get back to our witch project. But he's a lovely man. I definitely endorse him.

AM: Yeah. Our listeners will be looking out for that witchy project. But in the meantime, Lore's a perfect recommendation as we're sort of easing into spooky season.

HBM: Yeah.

AM: It's excellent.

HBM: He's a good dude.

AM: So, Hilarie, I have enjoyed this conversation so, so much.

HBM: Same.

AM: And I'm just endlessly grateful for your time today and for you having shared so much of yourself and your magic with us in all that you do. Listeners, you can get Grimoire Girl on Audible now.

HBM: You're so wonderful. Thank you so much.