I’ve said some unhinged things before, but this one might really take the cake: I don’t think I would’ve given love a second chance if it hadn’t been for the romance genre.

I got married very young the first time. Too young. Too fast. Two months of knowing someone is not a foundation—it’s a free fall. And when that marriage ended, it didn’t just end a relationship. It broke my faith in romance altogether.

So, I opted out. No love. No dating. No hope. Just work, school, survival, and a “nah, I’m good” with a disgusted side eye for potential suitors. At that time, romance felt fictional in the worst way—dangerous, naive, and most certainly not meant for someone like me.

And yet, that’s when I started diving into romance books more seriously.

Pride and Prejudice has shaped how I understand the genre more than any other story. The first time I read it, as a teenager, I didn’t get it. I remember thinking, “Ugh, this annoying mom who won’t let this girl just read her dang books...jeez!” I also thought, "What’s the point?" I was too young, too unscarred, too unfamiliar with real disappointment to understand why restraint and self-reflection mattered. The second time I read it—in college, months after my first marriage ended—it felt like an entirely different book. After real heartbreak, after learning how unsafe love could feel, watching two people grow separately before they grew together felt almost radical. Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy don’t fall in love because they want to be saved. They fall in love because they could confront their flaws, sit with discomfort, and choose to be better.

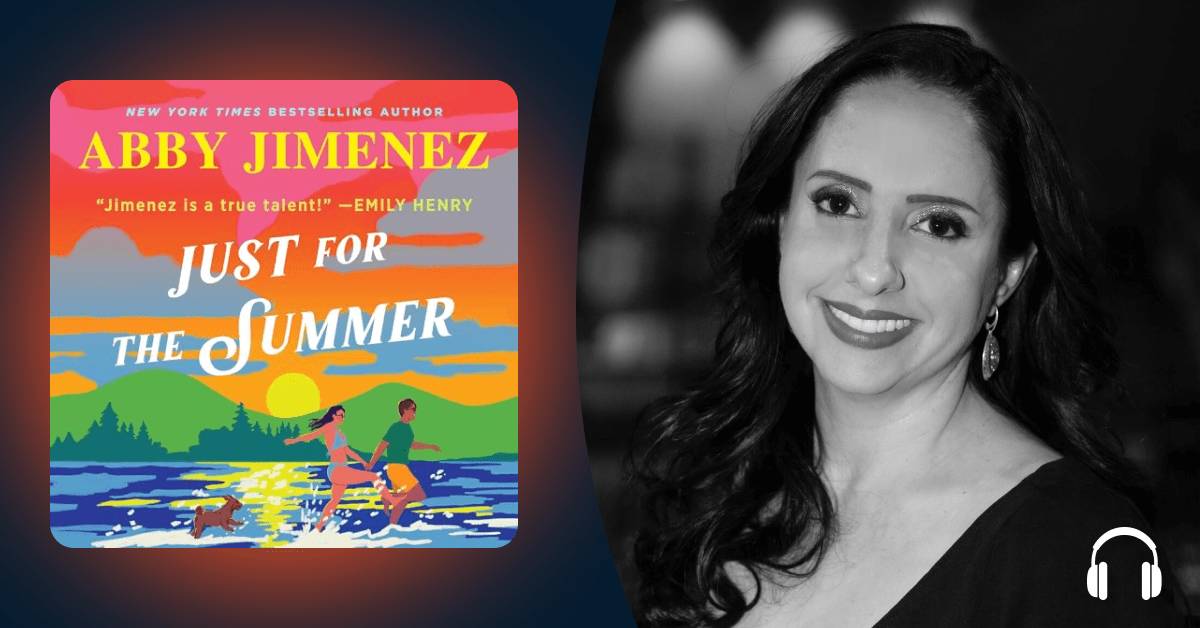

The contemporary romances I found kept reinforcing that idea. Listening to books like Graeme Simsion's The Rosie Project, Kennedy Ryan’s Before I Let Go, and Abby Jimenez’s The Friend Zone, I’ve learned that love is inseparable from grief, accountability, and the long, uncomfortable work of healing. These, and many other romance books like them, aren’t about reunion—they’re about whether two people are willing to face who they’ve been and who they still need to become.

Somewhere in the middle of all that reading, listening, and rebuilding, I met my now-husband. Not through a grand gesture, but through friendship, consistency, and time. I wasn’t looking for romance. I wasn’t open to it. I was focused on my life. But when I realized I was in love—real, inconvenient, terrifying love—I didn’t panic the way I once would have. I went to therapy. I questioned patterns. I learned how to hold boundaries without turning them into walls. Not because love fixed me, but because romance books had already taught me this truth: Love asks something of you.

Romance didn’t teach me to fall in love recklessly. It taught me discernment. Patience. The belief that healing is part of the love story—not something you do afterward. Romance stories didn’t lie to me. They didn’t make me naive. They didn’t promise fantasy without consequence.

They taught me how to choose better; they taught me to love me before loving anything else.

Sometimes romance doesn’t teach you how to fall in love. Sometimes, it teaches you how to try again.

Thanks for hearing me out.

In this article