In recognition of Autism Acceptance Month each April, we set out to amplify neurodivergent voices, celebrating their unique perspectives and honoring all the complexities and variations of the human brain. For decades, disability activists have been championing paths to inclusion, accessibility, and equity in every aspect of life, from employment, healthcare, and housing to architecture and construction to widespread liberation from all forms of abuse, neglect, discrimination, and sociocultural barriers. And through self-advocacy—activism that recenters the narrative on the experiences and interests of the group a movement pertains to—the conversation on neurodiversity and creating a world that works for all, regardless of neurological or sensory processing differences, has grown to new heights, encouraging both empathy and change.

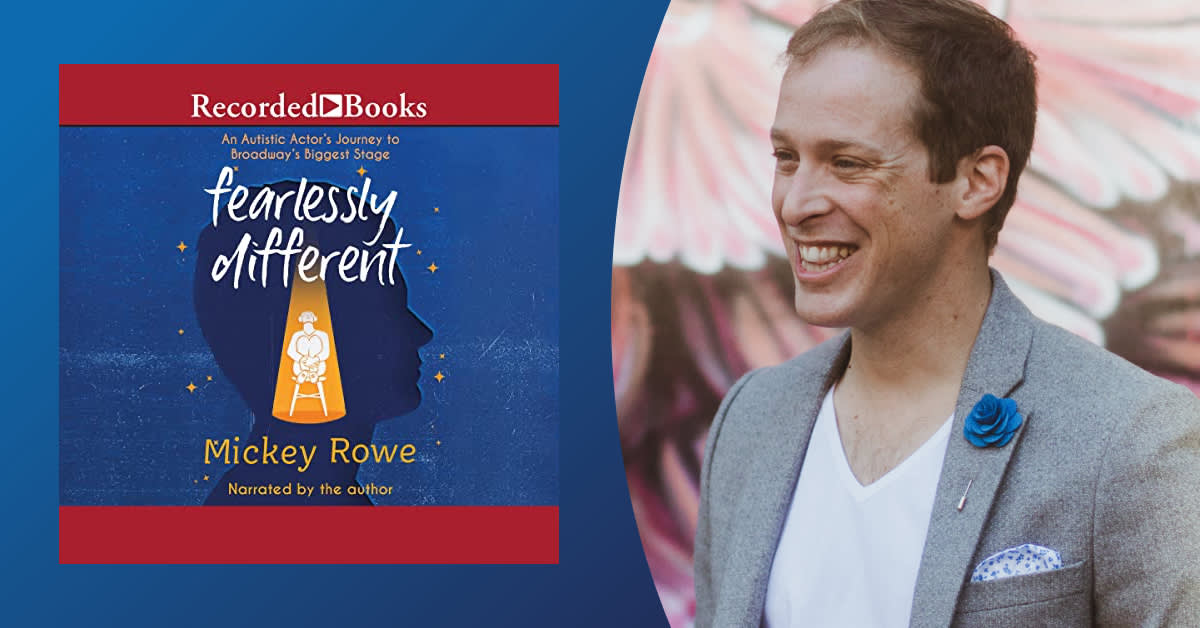

One such champion of the neurodiversity movement is actor, activist, and now author Mickey Rowe, who details his journey from an oft-infantilized youngster told he wasn't fit for mainstream society to the first autistic actor to play the lead in the Tony-winning stage adaptation of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time in his heartfelt and candid debut memoir, Fearlessly Different. Rowe, an autistic and legally blind artist living in Seattle, Washington, refused to be defined by what others told him he was incapable of, whether it be taking the stage in the title role of Arts on the Waterfront's production of Amadeus or encouraging other disabled actors to follow, which inspired him to help found the National Disability Theatre.

We were fortunate to have Rowe give us his thoughts on the importance of representation, authentic storytelling led by disabled artists, and embracing neurodiversity in both the arts and society at large.

What is the responsibility of art—theatre, books, movies, television, and audio—in accurately representing the lived experiences of those living with a disability or sensory processing difference? Do these fictional performances hold the power to inspire real world change?

Stories have so much incredible power and also so much incredible responsibility when it comes to portraying disability and neurodiversity! The stories we tell affect who gets employed, who gets diagnosed, and more. Inclusion in the arts and literature leads directly to inclusion in life. As an autistic person, I didn't get a lot of social interaction, but at the theatre or in books, I got to watch all these incredible relationships and social interactions in a safe way. But we disabled folx don't just want to be audience members—we want to be employed. We want to be active parts of the conversation about autism. We want to help shape the stories about us from the inside, just like any other minority group would want to have a hand in telling the public stories that shape public understanding about their group.

It’s been estimated that around 95% of disabled characters in media are portrayed by non-disabled actors. What issues are inherent in that statistic? What recommendations would you make to casting directors in opening the field to a wider range of talent—most notably, those who have intimate experience with the matter at hand?

Absolutely! Young people with disabilities in this country need to see positive role models who will tell them that if you are different, if you access the world differently, then the world needs you. Excluding people with disabilities from stories that are entirely about disability, unfortunately. doesn't help to accomplish this. Authenticity is powerful. Authenticity is sexy. You can capture so much more brilliant, honest, three-dimensional nuance with authenticity.

If you want to learn about autism, the best way to do that is to go to autistic adults. There are so many wonderful books by autistic adults. If you need help figuring out how to cast, or hire, disabled folx at your place of work, the answer is simple: Consult with other disabled consultants on how to make that happen.

How could embracing the idea of neurodiversity (and emphasizing the importance of inclusion in schools, workplaces, and across the board) fundamentally change our communities for the better? What kind of applicable practices could companies and individuals seek to make in their thinking and policies to create a world more accommodating for all?

People with disabilities are some of the best creative problem solvers in the world. We have to be creative problem solvers every day to navigate a society that wasn't designed with us in mind. Can you imagine how advanced society would be right now if all throughout human history, women [had been] allowed to have jobs, Black people [had not been] put in menial positions, and disabled people [hadn't been] either killed at birth or put in institutions? Can you imagine where we would be as a society if everyone, with their diverse lived experiences and brain wirings, had been allowed to contribute to society? As Stacey Park Milbern said before her passing, “Ancestorship, like love, is expansive and breaks manmade boundaries cast upon it, like the nuclear family model or artificial nation state borders. My ancestors are disabled people who lived looking out of institution windows wanting so much more for themselves. It’s because of them that I know that, in reflecting on what is a ‘good’ life, an opportunity to contribute is as important as receiving supports one needs.”

With autism comes a new way of thinking: a fresh eye, a fresh mind—literally, a completely different wiring of the brain. We think differently than most people, so we are amazing problem solvers and innovators. If most people are looking at a problem from one angle, autistic employees are able to see the problem from a completely different perspective. Who wouldn’t want to hire that into their organization?

In terms of hiring autistic individuals, moving away from interviews with lots of small talk to working interviews where the autistic individuals get to show you how great they are at doing a job that they love is an amazing first step.

Despite being fairly common, autism spectrum disorders remain quite misunderstood. Your memoir seeks to upend many of those misconceptions—what messages do you hope listeners take away from your story?

I think that people want so badly to fit in that they forget what makes them stand out. And I really hope that my book helps people to feel brave enough to stand out. Truly, your differences are your strengths. Often, young disabled people can be taught by society that they are a burden. But know that you are not a burden. Your differences truly, truly are your strengths. The things that make you different are so valuable. You are giving the world such a huge gift when you share all of you.

"Can you imagine how advanced society would be right now if all throughout human history, women [had been] allowed to have jobs, Black people [had not been] put in menial positions, and disabled people [hadn't been] either killed at birth or put in institutions? Can you imagine where we would be as a society if everyone, with their diverse lived experiences and brain wirings, had been allowed to contribute to society?"

You’ve mentioned that your success was not in spite of but instead because of your autism. How did your disabilities—what some might consider hinderances—actually guide you through life, on stage and off? And what can be gained by viewing disabilities not necessarily as deficits but merely as differences that can even afford a set of strengths?

It is so important that we learn about both our strengths and our weaknesses. My autism has made me more empathetic, [and] my autism has made me a better creative problem solver! My autism has made me a better actor because, as an autistic person, I need to act every day to try to "pass" as neurotypical. You reading this, your differences, the things that make you different from your neighbor or co-worker, also make you strong in so many ways.

85% of autistic college graduates in the United States are unemployed. And then, even if you [could] get a job—up until right before the pandemic started in Washington State—there was no minimum wage for people with disabilities like myself. Nationally still, while the federal minimum wage for everyone else is $7.25 per hour, for disabled people companies can choose to pay as little as one or two pennies per hour. That's just the law. So because of that, I had to street perform.

But I loved street performing. After leaving special ed, I street performed, stilt-walking as an autistic and legally blind single dad with full custody of my autistic child to make ends meet, while the children's [biological] mom saw the kids in supervised visitations. This street performing was such incredible practice for playing big roles in a theatre.

For most of my life, people felt uncomfortable around me as an autistic person. But when I was street performing, everyone who saw me smiled. My whole life I had been the fool, but while I was street performing, at least I was acting the fool by choice, and being paid to do it. So for this reason and more, autism really forced me to become a great actor—[and] to survive.

"Often, young disabled people can be taught by society that they are a burden. But know that you are not a burden. Your differences truly, truly are your strengths. The things that make you different are so valuable. You are giving the world such a huge gift when you share all of you."