It may be true that in space no one can hear you scream, but in the Star Trek universe, space is a fairly cacophonous place filled with explosions, starships warping across the galaxy, phasers firing, and grunting lizard men engaged in mortal combat with the heroic Capt. James T. Kirk. Some of these effects are among the most memorable ever created for the medium that FCC chief Newton Minow once famously referred to as “a vast wasteland.”

Back in 1966, Doug Grindstaff, sound mixer for the original Star Trek series, didn't realize at the time he was making TV history. In fact, he didn't even have a parking pass on the Desilu lot. Laughing about it now, he says he had the art department forge and laminate a pass for him, prompting studio executive Herbert F. Solow to proclaim, “You guys are really creative.”

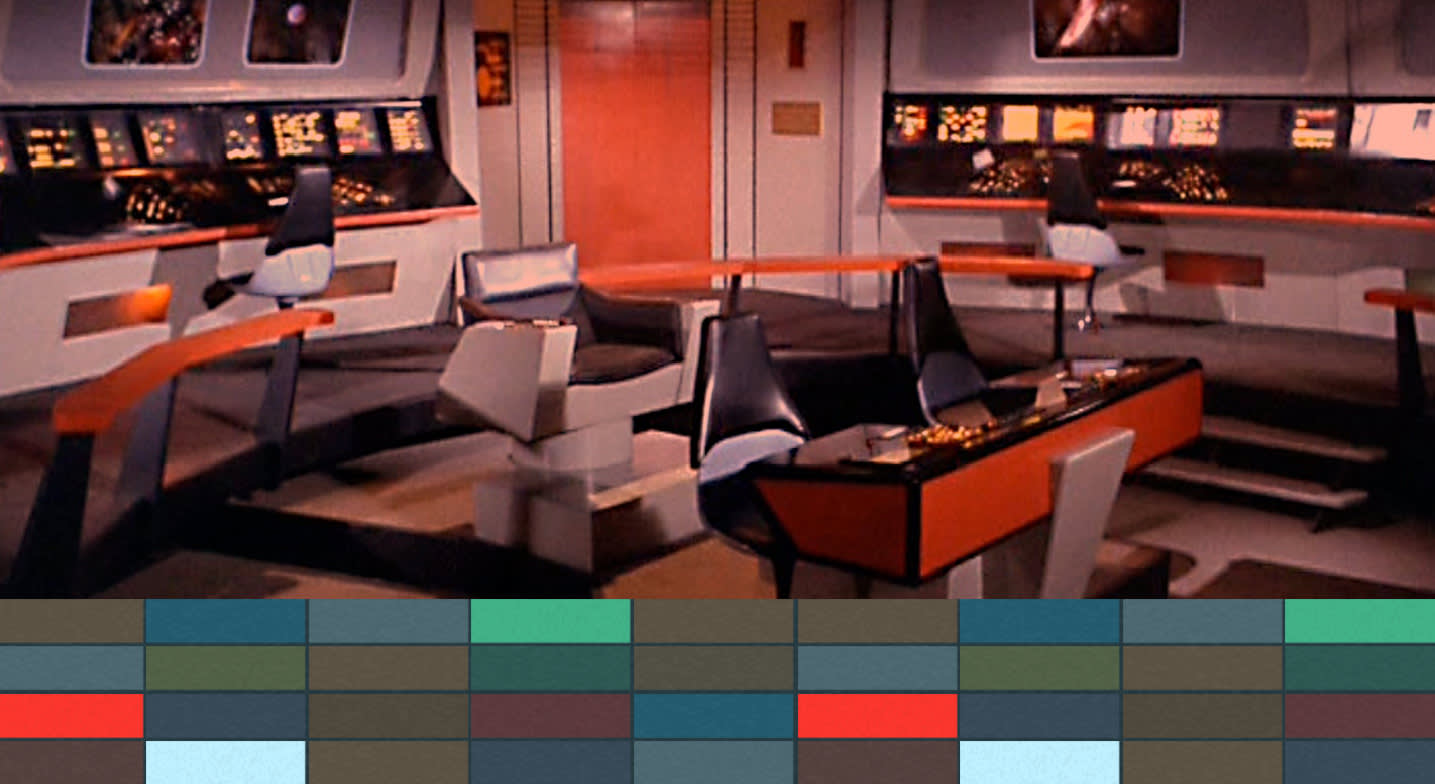

How creative they were is abundantly clear to anyone who has ever seen — or heard — the original series. The wall-to-wall sound effects were created in an analog world in which all audio was cut and mixed on magnetic tape, long before the advent of software-based sound tools. Each of the Enterprise sets had its own sonic “feel” — the chirp and ping of various sensors and instruments on the bridge, the throb of power in the transporter room and the deeper sound of power generators in engineering. This created the illusion of a massive space vessel where every part of the ship had its own distinct aural environment. The show’s space effects, while expertly done, were simple, so the rumble of the Enterprise’s engines and the sounds of phasers, photon torpedoes, and other energy forces (while they wouldn't really be heard in the vacuum of space) helped create the illusion of real, futuristic technology at work.

“I think the sound effects for the original Star Trek are probably the most memorable and iconic ever produced for television.”

“The first season we had about 10 editors,” recalls Grindstaff, who worked on all three seasons of the original Star Trek as well as the two pilots “The Cage” (the original pilot) and “Where No Man Has Gone Before.”

“I said, ‘This is ridiculous. I can do it with three editors if you give me good men and myself. That’s all I need. Get the others out of here,’” says Grindstaff. “Then I had three editors and myself and we did the show. But what I would do is create the stuff and then they would put it in. It just worked. On the original pilot, I would get in at 7 o’clock and [executive producer] Gene Roddenberry would be there. I would get out at 2 o'clock the next morning. That’s a long day. And you’d work Saturday, Sunday, holidays. Nothing mattered. I enjoyed it. The people you were working with were great.”

“I think the sound effects for the original Star Trek are probably the most memorable and iconic ever produced for television,” offers Jeff Bond, the author of The Music of Star Trek and a distinguished Trekspert. “They were done at a time when people watched television sets that mostly had a single, small, monophonic speaker, and when there was nothing like the immersive, multi-layered sound mixes that movies started getting in the late '70s, and which television showcases today. The show’s sound editors Douglas Grindstaff, Jack Finlay, and Joseph Sorokin not only created extremely innovative and unique-sounding effects, they also created entire sonic environments for the starship Enterprise and the different planets the ship would visit.”

Grindstaff, who was nominated for an Emmy Award for the first season, first came to Hollywood upon returning from Korea, at the behest of his brother, who was working in radio. He first heard of a new pilot called Star Trek in 1965 while working on another series called Swinging Summer, a precursor to Charlie’s Angels. “I was over at Goldwyn Studios when the phone rang and the head of the sound department introduced me on the phone to Gene Roddenberry. Gene had heard about me, and they needed someone to come over and help them on Star Trek. Gene was really into sound. On one episode that Gene liked very much, he sent me a memo with 11 pages of notes handwritten about the sound.”

Courage even created the familiar “swish” of the Enterprise for the opening title sequence by blowing air across a microphone himself.

“There was a wonderful musicality to the consoles — the whistles and clicks,” says Lukas Kendall, publisher of Film Score Monthly and a producer on a number of Star Treksoundtrack releases. “The sound effects got the balance just right between acoustic and electronic, futuristic yet timeless. There was a sonar ping to the viewscreen that you can practically whistle to yourself, it’s so melodic. It created this sense of a wondrous future where technology was our friend and not something to be feared.”

“One of the reasons that the show’s effects are so distinctive and memorable is that they are often musical, and that goes back to the first composer who created music for the series, Alexander Courage,” says Bond. “When Courage was working on the show’s first pilot, ‘The Cage,’ he was assisted by a man named Jack Cookerly, one of the session keyboardists, who had modified one of the electric organs of the period to make strange ‘electronic’ sounds.”

“A lot of the sound effects were generated by musical means at the end of recording sessions with the orchestra,” says Kendall. “Cookerly had a device he called a ‘music box’ — a reconstructed Hammond organ — that laid the basic tracks for the transporter effects, the medical scanners in sickbay, and other sounds.”

During the recording sessions, Courage took the time with Cookerly and some of the session musicians to create sound effects for the show, including the transporter sound, strange atmospheric and wind-chime sounds for the planet surface, the weird “thunk” of Capt. Christopher Pike (later to become Capt. Kirk) hurling himself against a transparent barrier confining him in an alien zoo, and numerous other sounds. Courage even created the familiar “swish” of the Enterprise for the opening title sequence by blowing air across a microphone himself.

“Gene Roddenberry wanted to paint the whole show like you were painting a picture,” says Grindstaff. “And he wanted sounds everywhere. One time I asked him, ‘Don't you think we're getting too cartoony?’Because I felt it should be a little more dignified, but he wanted sound for everything. For example, I worked on one scene where [Dr. McCoy] is giving someone a shot. Gene says, ‘Doug, I'm missing one thing. The doctor injects him and I don't hear the shot.’I said, ‘You wouldn't hear a shot, Gene.’He said, ‘No, no, this is Star Trek, we want a sound for it.’So I turned around to the mixing panel and I said, ‘Do you guys have an air compressor?’And they did. I fired up the air compressor, squirted it for a long enough period by the mic, went upstairs, played with it a little bit, and then put it in the show. And Gene loved it. So, that’s how Gene was. He didn't miss nothing!”

“The pneumatic ‘whoosh’ of the doors sliding open became a running joke in Airplane II with William Shatner.”

Adds Bond, “Later they adapted and expanded on these sounds, often using the tones of an electric organ [the first keyboard synthesizers were enhanced versions of these instruments and became available to the show’s composers during the second season]. The recorded tones had to be manipulated by using tape techniques — speeding up, slowing down, adding reverb or echoes to the tones. Some of the familiar effects came from Paramount’s own sound-effects library. The photon torpedo sound was originally created for the “skeleton ray” in George Pal’s War of the Worlds, and some other Trek sound effects can be heard in the low budget sci-fi movie The Space Children. The effects, like the show’s music, were crucial in creating its verisimilitude. The show’s planet sets, created on a soundstage, couldn't reproduce the scope of a real exterior or even of a bigger-budgeted film production, so the ambient sounds helped to convince viewers they were in an alien environment.

"So many of the sounds became part of the culture,” says Kendall. “We all know what the transporter sounds like, and the phasers and the communicators. Much like actors, they had great personality and were easy to remember. The pneumatic ‘whoosh’ of the doors sliding open became a running joke in Airplane II with William Shatner."

Other iconic sounds in Star Trek included the Tribbles. In the case of these famous furry and fertile pets, Grindstaff took the sound of a dove and played with it. Says Grindstaff, “You'd slow it down, you'd speed it up, turn it backwards, stick a razorblade on the mag [audiotape track]. I would use scissors to cut it. I would use sandpaper. I would use emory board. I would use steel wool. Anything that I could do to make things work. And you could take a sound and you could speed it up and speed it up again and again and a new sound would come out."

Other classic sounds Grindstaff created for the series include the sound of the neural parasites in the episode “Operation: Annihilate,” made by sampling about a hundred kisses, a secret he refused to share with his producers. Meanwhile in “Catspaw,” featuring an ominous giant black cat, Grindstaff brought in a dog to antagonize the cat that provided the required hiss. In “Amok Time,” the Vulcan gong was a combination of a guitar’s electronic twang and the sound of the actual gong being struck on set.

"The sound effects were so brilliant in selling the futuristic environment that they liberated the music scores to focus on the storytelling,” says Kendall. “Sci-fi scores until that point often had eerie theremins and atmospheres, but Roddenberry wanted the scores to emphasize timeless human drama."

So why, after five decades, does Star Trek continue to endure? It’s a mystery even to those who worked on the original show. “If I had only known, I would have kept stuff like you wouldn't believe,” laughs Grindstaff. “But I didn't realize it. No one did.”