Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

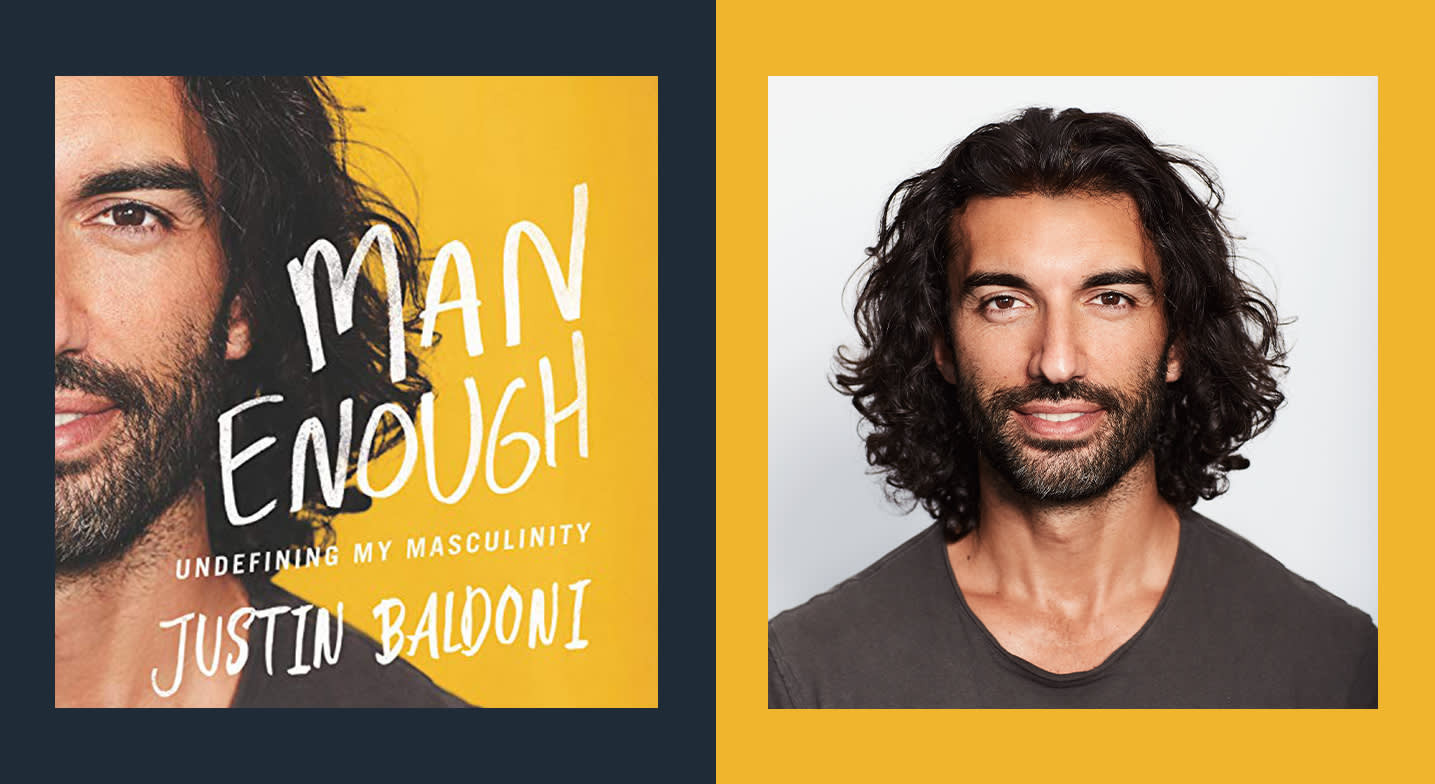

Michael Collina: Hi, I'm Audible Editor Michael Collina. Today, I'm talking to Justin Baldoni, the actor, filmmaker, director, and now author. You may know Justin from his viral TED Talk on masculinity, his acclaimed films, Five Feet Apart and Clouds, his time playing Rafael on Jane the Virgin, or perhaps from the viral proposal video to his wife, Emily. I'm thrilled to have him with us to talk about his book, Man Enough. Welcome, Justin.

Justin Baldoni: Hey, Michael. Okay, I just need to say your voice is beautiful.

MC: Thank you so much.

JB: Wow! Keep talking to me with that velvety, beautiful voice of yours.

MC: Coming from the acclaimed narrator, of your very own book too, that has a lot of sway, I would say.

JB: Well, that's a loaded statement, because I think that I've done eight sessions now, and I've heard most authors finish theirs in like two or three. So I'm not very good at narrating my own book, I will tell you that.

I joke that I've learned two things from the experience of narrating my own audiobook. The first is evidently I suck at reading. The second is that I can't pronounce "masculinity."

MC: It's a tough word. There’s a lot of syllables in there.

JB: And it shows up 120 times in my book at least, if not more.

MC: Well, we'll dig into your narration process later on. But first, I want to ask you about the inception of your book. This book is partly based on your TED Talk, "Why I'm Done Trying to Be 'Man Enough'" and also on a web series called Man Enough, where you talk to various men about masculinity and their experiences with it. Having explored this topic in so many different formats, it's almost as if Man Enough has become its own movement of sorts.

In your own words, can you tell us a bit about your book and how it interacts with some of the other Man Enough media you've created?

JB: Sure. Well, the book, like my life, like the TED Talk, and the Man Enough show, they are a reflection of the journey that I'm on. It's a journey with no destination. It's a journey that asks questions. At its core, my book is a personal exploration of what it means to be a man told by myself as a man, and I ask the question, what does it actually mean? What does all of it mean? And the goal is to undefine masculinity.

"I don't believe in toxic masculinity or that men are toxic. I believe that we are suffering from the very thing that we help perpetuate."

What I mean by "undefine" is that I think that as men we're so often put in a box, we're labeled, we have to be a certain way in order to fit in to be a man, to have the man card, to be in the man club, to be in the boys' room, to be in the locker room. And we tend to govern ourselves by this invisible set of principles and laws that most of the time most of us don't even know or realize exists. Ironically, women tend to realize it exists, and that's one of the benefits of privilege, right? You're not aware of it especially when you have it, unless you're on other side of it.

MC: Absolutely.

JB: So, in terms of the book, in terms of what the goal is, I want to undefine and unpack and open the conversation to call out and to look at what these invisible forces are, and where they came from and how we learned them, and also, to let men know that they are not under attack, that we are not bad, that it is not a bad thing to be a man. It is not a thing to be ashamed of or to apologize for. I don't believe in toxic masculinity or that men are toxic. I believe that we are suffering from the very thing that we help perpetuate.

So yeah, man, it's a deep dive. It's a personal account. I get really honest, and raw and vulnerable. I use myself as an example, because that's all I can really use, and it's an invitation at its core from my story into yours. What I hope is that I wrote a book that can model some of the ideas that I wish were modeled for me. Because I needed a book like this at 15, at 20, at 25, at 30, at 35, and I need it now as my wife said when she finished my book, she said, "Baby, it's really, really good. Now you need to read it." And that's where I am: I'm on a journey, and it's a journey that will never end.

MC: Yeah. And I think it's a journey that all men are on. Like you said, it's a book you needed, but it's a book that so many other men also need.

JB: I appreciate that.

MC: You referred to this as an invitational book. Can you tell us a little bit about what you mean by that?

JB: Yeah, you know, my work is with men. I love that women are excited about this book. My hope is that women read it and can see some of themselves in the book, but also have compassion for some of the men in their lives. But my hope and my prayer is that men read it. It's an invitational book instead of a motivational one, knowing that men would rather read motivational books.

How do I know that? I'm a man. And those are the books that I want to read. Those are the books that I gravitate to. It's like, how I can become a better meditator, how I can be able to better this, how can I become a better... You know? A better CEO, a better director. It's like we want to be better.

But so often we don't realize that…the things that we want to be better with are great, but what we really need to become better at is exploring and uncovering the parts of ourselves that make us tick, that govern all of the things that we do on a daily basis: our everyday interactions with people, with women, with ourselves, the things that we don't often check in with. And so it's an invitational book, in that I share all of these things, I share my journey, I share my insecurities, and a lot of stuff I've done wrong.

A lot of things I've never even shared with anybody just came out as I was writing it, as an invitation into your own story, because your story might not be like mine, Michael. But there's no doubt that your experience as a man growing up in America will parallel mine in some way, shape, or fashion.

You might not have had the exact same thing happen to you that I had, but you'll have something similar happen to you. And the fact that I talk about it will hopefully give you permission to think about it, and maybe even talk about it yourself. There's also a good chance that one of the things that I talk about in my book, instead of it maybe not happening to me, maybe something that I did to somebody else, maybe you were on the receiving end of that thing.

Maybe I'm the guy that bullied you, right, and that you'll then see your bully in a new way. Maybe your bully was hurting or suffering in that way. At the end of the day, it's about getting rid of the stigma that we have to be this impenetrable, impermeable thing.

But that thing, that very thing that is preventing us from showing who we are, is also the very thing that is making us so damn unhappy, that's causing men to kill themselves at higher rates than women, that makes us feel like we have to suffer in silence that we can't share. We want to take that pressure away, that stuff away, that unrealistic idea that to be a man we have to be this thing, and open it up so that if you identify as a man, if you are a man, if you are male, whatever it is, then you are as you are enough.

MC: Absolutely. I love the way you put that because it's so true. The core of what people need to understand is, it's okay to share, it's okay to share who you are, it's okay to share your story, and that's one of the first things we need to do to start these conversations.

JB: It is the first because if nobody shares, how do we learn?

MC: Exactly. And as you mentioned, throughout this book, you infuse your own personal experiences and your own journey with masculinity, with pieces of gender theory and other pieces of sociology. In fact, you discuss your experiences with body dysmorphia, and you also open up about your difficult relationship with porn and sex that you've had throughout your life.

This book was one of the first times you've actually shared that. So I want to ask, what was it like revisiting some of those personal and at times really painful moments, and just opening up and being vulnerable with so many people?

JB: Terrible. It was terrible. It was a very challenging time. I wanted to quit writing this book multiple times. I tend to govern my life by the principle that if it scares me, I have to do it, even if it means I'm going to quit multiple times. It was really hard, man.

The irony is that I wrote a book called Man Enough, yet, as I was writing it, didn't feel man enough. And I think it's important, and it's an important part of the book, because I'm not writing it as someone who's on the other side.

I'm not writing it as your teacher, or as your guru, or as somebody who can tell you that this works, and X plus Y equals this, and if you just make these four changes in your life, then this is going to happen for you. That's not what this is.

There's parts of the book and things that I share that I am on the other side of, but it's very much present for me. I'm on the journey while sharing it. That was important for me, because I can't write a book about masculinity, and I don't think anybody can, from a place of knowing exactly what it takes to fix it, because I am in it. I'm in the matrix writing about the matrix.

And I want to get out. For me, writing the book is a way of helping me get out, right? It's a way of helping me see the code and understand it. I'm fighting the Mr. Smith. And so it was really hard, because I'm struggling with it in real time. I talked about in Chapter Five, in "Privileged Enough," I talk about the recognition of my own racism.

Instead of just sharing a bunch of quotes, I shared the stories from my life, of the way I've really hurt people that I love on my journey. And talking about porn, and talking about the effects it's had on my brain, I found myself being triggered while I was writing it. So to answer your question, it was really hard.

MC: I just want to say thank you from the bottom of my heart for taking the time to go through and deal with all of that trauma and those triggering and tough issues and topics, because I think it shows one, in the finished product, you can tell you put your entire heart, soul, and body into this book. It really does show.

JB: Yeah, thank you.

MC: I think it's really going to help a lot of men; it's going to help men see, "Hey, I'm not alone. Hey, maybe I have a body image issue. I am not the only man who has experienced this or who has felt this." I think that's super powerful.

So, Justin, faith was a big part of this book. A lot of times, you mention how important it was to your journey, and to unpacking your relationship with masculinity. Can you tell us a little bit about that? That relationship and that journey in regard to your faith?

JB: Sure. So when you bring that up, what comes to mind is, I don't know if I could have written or would have written the book had it not been for faith.

In the Baháʼí Faith, specifically, we're told that one of the most important parts of faith is the independent investigation of truth—meaning you have to investigate truth for yourself. You don't just become something because your parents or your grandparents were. You don't just adopt something because it was passed down to you traditionally.

You must question it, investigate it, and then dive into it. Only then can it really be taken on for yourself and absorbed into your heart and embody it.

"All it is is acknowledging, saying, "No, my life might still be hard if I'm White, but it's never going to be hard just because I'm White.""

I can't just take it. I can't just take the masculinity that my father gave me, that his father gave him, because it doesn't work for me today. My grandfather was an Italian immigrant who came over on a boat to Ellis Island in 1912, and became a state senator in the '40s in South Bend, Indiana.

Okay, well, he had a very different upbringing than my dad did. And then he passed masculinity on, and my dad passed it on to me. So faith has taught me to question. It has taught me to question that thing, like, "Well, does that work for me? Does it work for me to never show anybody my flaws? Does it work for me to keep my struggles a secret? Did that make my dad happy?"

The answer is no, of course it didn't. But thank God I've been taught to question, because if we don't question, we can never find an answer.

MC: Thank you for sharing that, and talking about some of the difficult subjects you had to face in this book. You talk a lot about privilege, and how your thinking and your conversations about privilege were pretty painful at times for you to grapple with.

There were a couple things you were thinking back on where you hurt people in your life that you loved, not knowingly, not intentionally, but you still hurt them because of your privilege. Can you just tell us a little bit about that?

JB: Yeah, the word "intentionally," that's the one, right? "Well-intentioned White man," I think, is one of the subchapters of the book. The "Privileged Enough" chapter was the last chapter that I wrote. It was one of the hardest chapters for me because I was wrestling with the word "privilege."

For me, writing about privilege, especially living in the time of George Floyd, was a very, very tricky thing, because I was forced to look at all the ways that I have unintentionally hurt people that I love, specifically my Black friends and people of color.

Despite my intentions, the impact that my words and my actions had was messy, and I left some people bloody, and I did some damage, and my privilege allowed me to not have to see that. But thank God my heart and my faith never, never let that little thing that oftentimes we have deep, deep down in the back of our brains, which we can also call a conscience… It was always there. I could always feel it. I would always go back to it when I would meditate or something, someone would pop into my head, and I would think about something that I had done or said, and I would brush it off. But eventually I realized I had to come to terms with it, and so I write about a few instances from my life where I've really hurt people.

I hurt one of my best friends, Jamie, who is now one of the cohosts of my podcast, and the conversations that he's had to have with me, that he shouldn't have had to have with me. I write about it because I am a straight White man at the intersection of all of the privilege, and if I can't acknowledge my privilege, then who the hell can?

It's also okay, because acknowledging it isn't acknowledging that I haven't had hardships. Acknowledging that my Whiteness has benefited me does not take away from my accomplishments. And that's the thing that I think is so important to people. It's not an attack saying, "Oh, you know, because you're White you have it easy. Life is going to be easy for you."

All it is is acknowledging, saying, "No, my life might still be hard if I'm White, but it's never going to be hard just because I'm White." And that is the point of the chapter, because I had a really hard time with that.

I have brushed up against my own White fragility, that own part of me that I've recognized and noticed is identical to the part of me that I brush up against when a woman tells me that I did something that was maybe offensive or wrong.

And the intersection of those two things, I couldn't not write that chapter, because I cannot separate any longer my privilege as a male from my privilege as a White person.

And if I'm going to fight for true equality, and fight for men to take that deep dive and use those masculine qualities of bravery and strength, to go into their hearts, and to work on themselves, so that they can know themselves better, become better people, and then, of course, treat women better, then I have to do the exact same thing on behalf of White people.

And I hope that if you're a White person that reads the book, and that reads that specific chapter, you take that journey with me, and recognize that it's not an attack on you. I'm not asking you to apologize for your Whiteness. I'm just asking for you to acknowledge it, and for you to recognize that it exists.

MC: Absolutely.

JB: And the final thought I have on this whole thing and how it ties into the book is, we have to make space for our humanity. We have to make space and create a world and a culture where we are, we can mess up and say the wrong thing.

Because what so often happens is that people don't write about it or talk about it, because they're afraid of saying the wrong thing. Because they're afraid of being attacked, or being canceled, or whatever it is that we're talking about these days.

So you have so many White people that are well intentioned that don't talk or don't speak up, because they're afraid of saying the wrong thing. And that in itself is a form of privilege, the fact that they don't have to, they get to choose to be silent, right? Martin Luther King talks about that.

What we have to figure out how to do now and the hard part, which is a larger conversation than the book, is, how do we make room for men to be vulnerable and mess up? How do we make room for men to say the wrong thing sometimes? How do we make room for men to come forward and admit that they made a mistake, or maybe they shouldn't have talked to that person that way? Or maybe they made that comment that was sexist, maybe they did this or did that?

The reason I wrote this book for men is to show them that this is how you can do it. I don't have a perfect past. I was an idiot in high school. I did terrible, stupid things. I treated women terribly in college, because I felt terrible about myself.

There could absolutely be someone that comes forward one day and says, "Justin was an asshole to me." And I'll be the first person to say, "I was, and I'm sorry. I really was, and I'm sorry." We have to make room for that. Because otherwise the divide is going to get larger and larger and larger, and men aren't going to come forward.

MC: Yeah, it all goes back to, like you said earlier, it's all about looking inward, asking yourself those questions, and then taking the time and doing the work.

JB: And taking accountability when you mess up.

MC: Moving on to the performance of your book, what was it like performing your own words in this audiobook? You're obviously no stranger to acting on-screen, but did you have much experience in a sound booth or working on a project that was really only in audio?

JB: Yes and no. Yes, I've been in the sound booth quite a few times as an actor. Actually, believe it or not, I started in radio. I was a DJ when I was 16. Started at a Top-40 radio station. So I've had a lot of experience with audio, but never with something as precious as this to me. I really struggled with the audiobook, because I got a lot of advice, and all of it was different.

Some advice was, "Don't get too emotional, because you don't want to put your emotion on the reader. You want them to experience it." And other advice was, like, "Listen to McConaughey’s book. The guy performs the whole thing." Every book is different and every author is different. For me, what I really wanted in the reading of my book, was to take the listener on a very personal journey with me. Just like the book is written, I wanted the listener to feel like I was reading just to them, and that I was telling them a story.

I didn't want it to feel like reading. I wanted it to feel like a friend talking, because that's how I wanted to write the book, as a friend, as somebody that you're letting in, and then we can have a conversation in this magical space where time doesn't exist on your drive from home to work, or the bus ride, to pick up your kids or whatever it is.

So it was really hard. I put a lot of pressure on myself. I didn't feel enough, if you will, quite a few times leaving that booth. But I'm really happy with where it ended up. I'm excited. I don't think I'm ever going to listen to it, because I don't love the sound of my voice.

"I didn't want it to feel like reading. I wanted it to feel like a friend talking."

But I hope that it brings people in. And there's a few times I get emotional in the reading of it. I'm leaving that in on purpose because it caught me by surprise, and it's how I feel.

MC: Yeah, and of all books, I feel like this is the perfect one to allow yourself to get emotional in, because that's a big part of what you're talking about, is the importance and the power in being vulnerable and letting those emotions out.

JB: Yeah. Thank you.

MC: Going on to theory a little bit, you mentioned pretty much all of the big names in masculinity and gender theory—from bell hooks, Michael Kimmel, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and Liz Plank, just to name a few. But did any of these folks in particular inspire you to take this own personal journey for yourself and explore your own masculinity?

JB: Well, I think they all did. The only one I personally don't know is bell hooks, who I hope to meet at some point. I'm in touch with all of them, and they all inspire me in their own ways.

Ted Bunch and Tony Porter from A Call to Men, you know, Liz Plank is a good friend; we're actually doing a podcast together to support the book. Michael Kimmel early on in my journey was really, really helpful. These are giants, and what I appreciate and love about them is that they've dedicated their lives to the work. Bell hooks is, I think, in another category. She's the OG in so many ways, right? Writing about men.

They've also been helpful in reframing some of my ideas. Each of them actually I talked to before my TED Talk, originally, because I want to be helpful.

Here I am this, like, 34-year-old guy who's just learning about this stuff in real time, and also using my platform to talk about it. I don't want to hurt the movement. I don't want to hurt the work that they've been doing for 30 years. So one of the things I write about in the book is, from a young age I was always willing to ask for help.

In many ways, that's what I've done on my journey, is I've reached out to those names in particular, and I've asked for help. And I've asked them for their ideas and their thoughts. They read the book, they gave me their notes, they gave me their thoughts, and I don't want to do anything that can be harmful especially knowing that this movement was started on the shoulders of women.

This masculinity movement is as a response. We didn't start it, women started this. So yeah, they've all inspired me in many ways, and continue to.

MC: Great, thank you so much for sharing that. Men are really some of the biggest enforcers on one another and of their masculinity. I wanted to ask, how do you think we can go about breaking that cycle, and that pattern of behavior in general?

JB: Well, I think it starts with awareness. I think it's a two-part answer, and it's going to be really reductive, and it starts with recognizing that there's an issue, like anything. We have to look and acknowledge that there's an issue. We have to ask ourselves why we do the things that we do. Ask ourselves why.

And the second part is, we have to do the work. A stupid example, but a real one, is, if I have a resistance to doing the laundry, and I think that it's my wife's job or that she should do it, because I've been working all day and I'm tired, or resistance to doing the dishes, the resistance is masculinity.

"It's acknowledging, it's asking ourselves why, and then it's doing the actual work, despite the resistance. Those are the things that I think will eventually, hopefully get us a little bit closer to a more equitable and just world, starting with men."

The resistance is masculinity, because that's what we've been taught, that's how we've been socialized. That's the way our fathers maybe were or their fathers, depending on when they grew up, and that's it, right?

There's a system in place that's making us think that. But the resistance, I have to ask myself why, and then I have to do the work. I have to go and do it. I have to show up. I have to do the very thing that I'm resistant to. If my wife tells me I interrupt her, and then I keep doing it, it's one thing to apologize, it's another thing to then stop doing it.

I have to figure out why am I doing it in the first place. Does it mean that I value her ideas less? Do I only interrupt her when she's coming at me with something that I need to reflect on? When she's angry at me do I interrupt her? Oh, well, I better look at that.

It's acknowledging, it's asking ourselves why, and then it's doing the actual work, despite the resistance. Those are the things that I think will eventually, hopefully get us a little bit closer to a more equitable and just world, starting with men.

MC: Absolutely. I agree wholeheartedly. So, you also make a point throughout this book to acknowledge the fact that it's often difficult or impossible to know, with this type of personal and introspective work in particular, when that work is truly finished and when it's done. Because I feel like with something like masculinity and something with unlearning these behaviors, it feels like there's always more to do. Do you see yourself revisiting this book or this topic again in the future?

JB: Oh yeah. The hard part about writing this book was that every chapter was its own book. It is much longer than it was supposed to be, and there's so much that I wasn't able to put in, because these things are very complex, nuanced, polarizing conversations.

It's not an academic treatise either. That said, there's a reason why you can study this in school, right? There's a reason why there's something called gender theory. There's a reason why you can get a degree in this, and I was just interested in the ground-level conversation, because at the end of the day you have to acknowledge that something exists to ever be able to fix it.

Unfortunately, most people don't acknowledge that this exists or that it's an issue, yet so many of us are unhappy. So absolutely. I mean, I started thinking about writing right after I finished it with the opening. I was like, "So I just finished Man Enough and I'm already wishing I could have rewritten it," right? As a part two to it.

There's so much deeper to dive, and I'm just at the beginning of my journey. So yes, I'm going to be revisiting it in a lot of different ways. I don't know about book form, but definitely in audio form, and in television and film form.

I'm really interested in also helping to build the platforms of other men who are maybe at different intersections of masculinity and different levels of privilege. Race and gender and all of it, and sexual orientation, to help them build their platforms to talk about these very things.

Because I think that's the other part of this, is we have to come together as men, and lift each other up and create a space where men feel comfortable sharing and talking about it. There's a lot of men out there that deserve to have more followers than me, and so it's my mission to help them do that.

MC: Absolutely. Well, thank you so much for that incredible conversation, Justin. I'm so glad to hear more men talking about the many nuances of masculinity and what being a man can mean or look like for different people, because it does mean and look different for a lot of us.

Listeners, you can find Justin's book, Man Enough, right here on Audible.