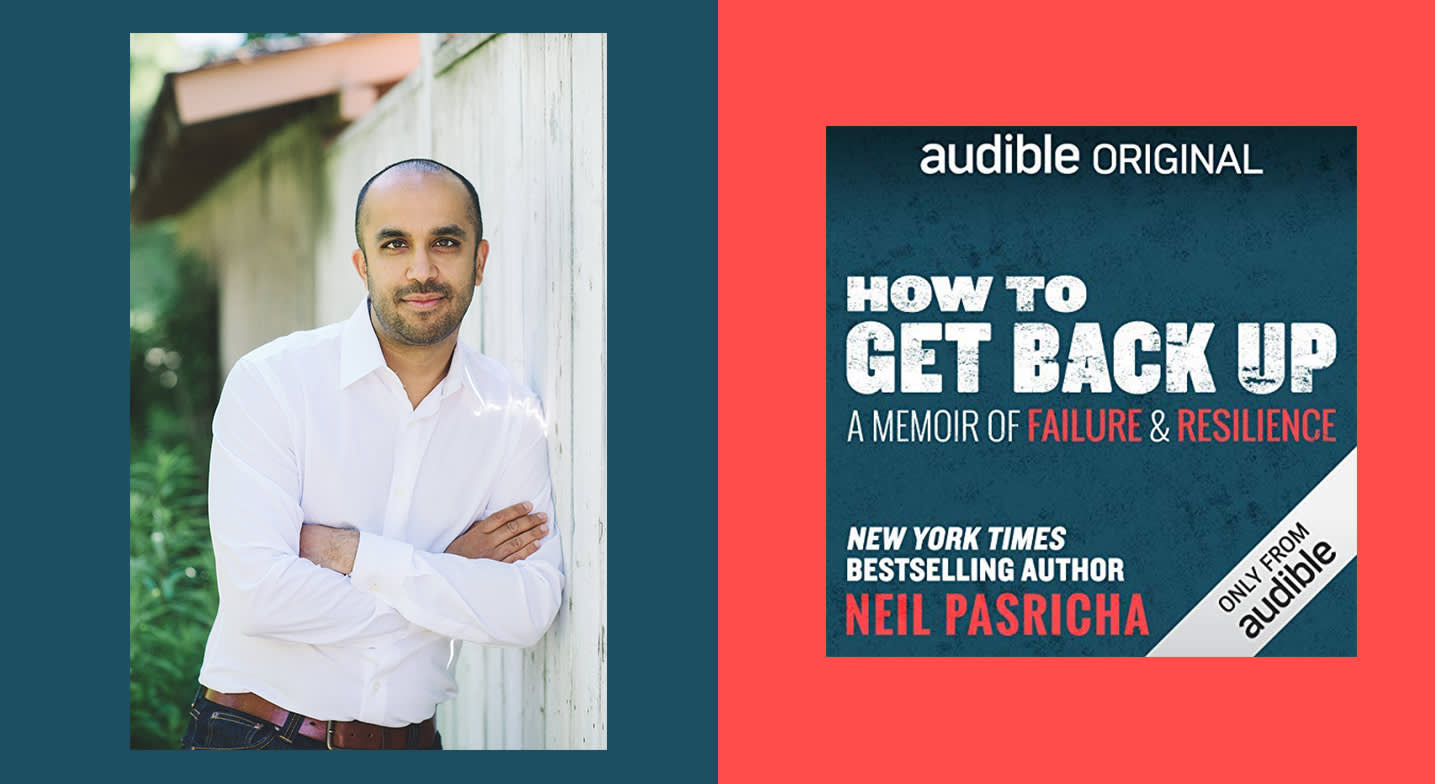

To all outward appearances, Neil Pasricha is the kind of guy you’d expect to write a traditional blockbuster self-improvement book. Motivational speaker: check. Three-million-times-viewed TED Talk: check. Resume featuring big-name brands: check. And while How to Get Back Up may prove to be an eventual blockbuster, it is anything but traditional. Namely because it emphasizes philosophies like “be different, not better.” For the most part, “betterment” is the whole point of self-development, but sometimes before we get better, all we can do is just be. Take it from Pasricha, who was inspired to espouse the “just get up” approach after his marriage ended and his best friend took his own life — in the same week.

We talked with Neil a bit about his unorthodox approach to finding happiness and success — and, spoiler: it’s probably not the path you’d expect.

Courtney Reimer: I loved the title from the moment I heard about How To Get Back Up: A Memoir of Failure and Resilience. Can you talk to me about the inspiration for it, why this book, why now?

Neil Pasricha: I think we have a tendency in our society to look at people who have done it, whatever “it” is: they have become a great singer; they have written a fantastic book that we’ve loved reading. They have become a fantastically followed YouTube celebrity, whatever it is. We have a tendency to think there is a narrative leading up to success that looks something like luck, or like a series of successes, good fortune, and good timing. The common thread underpinning any success story we see is actually a series of failures. Typically deeper, rawer, wider than we can possibly imagine. And often unfortunately in our society, totally invisible.

CR: One of the things I’ve always said is that you don’t want to fall in love with someone who’s never had their heart broken. You don’t want to have somebody work for you who has never had a really shitty job. Do you feel like you can be successful without failure?

NP: I do not feel that you can be successful without failure and I absolutely agree with what you said. I remember after my divorce, I was talking to a friend and they said, so who are you looking for if you plan to get married again? And I said, well, I don’t know, but I do know I’ll be an incredible husband because I learned through my marriage kind of how hard it really is to be in a great, strong marriage. And I learned a lot of things that don’t work, and about what I can’t do. So, I just know when and if I’m lucky enough to meet someone new, I will put so much more into it.

For Christmas one year my dad gave me a book. It was like the ultimate compendium of baseball statistics. I found that there’s a guy named Cy Young who has more wins in baseball than anybody else, which makes sense because they have the Cy Young award for best pitcher every year. But then, because this was a full book of statistics, I also flipped over to the most losses in baseball, which is a column that you never hear mentioned, and guess who is number-one on losses? It’s Cy Young.

Then I look at the next page. Most strikeouts of any pitcher, the ultimate statistic for a pitcher. The number-one strikeout pitcher was Nolan Ryan. So I was like, okay, great. I knew that, Nolan Ryan, everyone knows Nolan Ryan, most famous pitcher, and I turn to the next page. Guess what the next page is? Most walks.

CR: Let me guess, also Nolan Ryan?

NP: Nolan Ryan.

CR: I never knew that.

NP: I realize that it turns out it’s not how many hits you get. It’s really how many at bats you take. Those two pitchers are known throughout baseball as the people who have the most wins and the most strikeouts, but they’re also the same people that have the most losses and the most walks, the exact opposite statistics — meaning they just played more. They just tried longer. There’s a reason that Drew Brees just broke the most passing yards yesterday on Sunday Night Football because he just played longer. It’s nothing special, he’s played longer.

The number of successes you have is a direct correlation to the number of failures you have.

And the thing that gets kind of washed away in this metaphor is: “Oh, I just need to fail more.” But that ignores the lessons. What this book tries to do is both give a series of failures and offer at the end of each chapter, a specific and unique lesson from each one.

CR: I think people still don’t admit to reading a lot of self-help books. Were you reluctant to call this a self-help book?

NP: First of all, you and I both know that self-help is the largest category in the bookstore. It is the number one category in the bookstore and there are a couple of other categories, memoir and business that are number two and three — and those two categories are really self-help. They’re just called different things. What’s the business category trying to teach you? How to get better at business. And what’s that going to teach you? How to get better at your life. So, yeah, it’s gigantic. But the term “self-help” reeks of the sort of desperate clawing individual that sucks at everything and is stuck at the bottom of the totem pole at work, but their cubicle is covered in inspirational bumper stickers like, “Hang in there.”

CR: The cat.

NP: The cat. Exactly. And so I get that cliché. At the same time, maybe this is the opposite of what you were expecting or what you were leading me to - but I actually personally have a gigantic self-help section in my personal home library. I believe strongly in the idea that we only have 30,000 days to live and nothing is as important as making sure every one of those precious days is as rich and as meaningful and fulfilling as possible. And I also believe that if you’re lucky enough to get something out of a compressed volume of 50,000 words that somebody spent their life working on, that’s an accelerant, that is a stimulant that helps you get better at life.

I am sometimes called a motivational speaker. And for years I hated that. I was like, no, I’m not motivation. I’m application. I give TED Talks. I give lectures, I don’t give motivation. But now you know what? I’m a motivational speaker. I think people need to be motivated and people need to be helped. Those who are wise enough to get above themselves and just go for it, and pick up the book in that category, you know what? Those are the people I like because they’re the people that I find most interesting and that are most interested in helping themselves.

CR: A few things you’ve said in the book really stuck with me. I really liked “different is better than better,” which I feel like is a very unconventional sort of maxim for a self-help book. Can you talk a little bit about that?

NP: I was a so-so college student. I was never on the Dean’s list. I got a lot of Bs and I got a lot of Cs. My transcripts, when I was done with college, basically proved to everyone that I would never go further than that. I would never get a master’s in anything. And then literally I then spent my next few years after college failing at everything I did. I failed at my first office job. I quit just before I got fired. I started a restaurant. It failed, too. And then guess what happened after kind of failing in college, failing in my office job, failing in this restaurant I started: I got into Harvard Business School to do my MBA.

How does that happen? Because different is better than better. Every single person applying to Harvard Business School worked at a fancy consulting firm or a fancy investment bank. They went to an Ivy League school, they were the valedictorian. And here was this entrepreneur who ran a restaurant, who wrote comedy for the school newspaper. I went to New York City to work with Saturday Night Live writers. I never said that I was good at any of this shit. The point is different is better than better. It was just that I would add an element of spice to the sort of straight-edged, plain Jane, conservative classroom.

Where’s the world going right now? It’s going towards automation. It’s going towards AI. It’s going towards algorithms. We all know the death knell of manual labor jobs, of even “knowledge worker” jobs. With truck drivers getting automated and textiles can be automated. You don’t have to be Yuval Noah Harari to realize that there’s a huge tectonic shift coming and billions of us are going to be …”irrelevant” is the word that Yuval Noah Harari uses.

CR: Yeah. He’s not really a motivational speaker, just a side note.

NP: But to that point, when you’re in school and you’re learning math, or you’re learning grammar, or you’re learning memorization, or you’re learning the periodic table or you think that information is power. I’ve got a newsflash for you: better isn’t better. Different is better than better. If you can train your brain to lean into that thing that makes you you, the fact that you love painting, the fact that you have always wanted to be a standup comic, that your side hustle writing aquarium reviews, like whatever it is. There’s a guy I know who literally makes hundreds of thousands of dollars a year just writing detailed aquarium reviews. I didn’t make that up.

CR: No way.

NP: Oh, it’s a real thing. But the point is, he’s just leaning into the weird part of himself. He’s leaning into the weird part of himself. If we can all learn to lean into that weird part, that’s the part of ourselves that is the most difficult to replicate. That’s the part that’s most difficult to be a kind of rendered irrelevant or obsolete by artificial intelligence. If you’re really, really good at asking questions, you’d probably make a fantastic therapist and nothing can take that away from you. Different is better than better.

And not only is it a maxim that empowers us, it’s basically telling us to do the thing that our parents and our cultures and our values sort of steer us away from.

Any admissions policy, like at Harvard, they’re looking for things to add to that dimensionality, to the diversity, to the total picture. And if you can offer something different, then you can be the spice on the sandwich or you can be the spice on the entree, you can be the thing that everybody wants because nobody else has it.

CR: We talked a lot about all the failures that led you to where you are now but we don’t talk about the success and you know, looking at just maybe your strict CV, people would’ve been like, why did he leave? Do you miss the perks you got at those corporate jobs? And why did you leave? I mean like a lot of people would say you made it already.

NP: I grew up in an east Indian culture. My mom was from Nairobi, Kenya. My dad’s from outside of New Delhi, India, and most of the world is of this mindset that it’s important to work hard, study hard, get good grades, and be happy. And to put it into east Indian cultural parlance, it’s study really hard so you can get good grades, so you become a doctor. So, this was injected into my cerebellum at age like six months. That’s why I went to a fancy school and then I got this professional job. But the problem is, I wasn’t following my “different is better than better” advice. I was following the “better is better” advice, and I sucked at it.

I firmly believe that life is measured in weeks, and the way a week is measured is in hours and there’s 168 hours in the week. If you divide that number by three, you get three buckets of 56, 56 and 56.If you sleep eight hours a night, like every doctor tells you to, that’s one 56 hour bucket. If you work a 56-hour a week job (there aren’t many jobs that are 40 hours a week), add in your commuting time and your emails from home, and your Saturday afternoon on email, or whatever. And then you’ve got a third bucket. You’ve got a bucket, I call it the fun bucket. You’ve got a bucket left over and the first two buckets pay for and justify.

It was my third bucket that I was doing a second job in. And I realized that family needed to quickly become a third bucket, unless I wanted to drain my evenings and weekends again. I decided to leave [my job] because I needed to preserve the family time, and I wanted to do the thing I loved the most.

CR: Being happy and happiness is in the title of one of your other books (The Happiness Equation). I feel like we hear a lot about happiness without really talking about what it is. And I have a feeling you have a nuanced opinion of it, so I’d love to hear it.

NP: Happiness. Why is it a big deal? First of all, if you go to Google right now and you type into the search bar “how to be,” the first dropdown is happy. Meaning that more people around the world are searching for happiness than they are numbers two, three and four, which are rich, pretty, and real estate agent.

So people want happiness more than anything else. The second point is, are we there yet?

We live in the most abundant times in human civilization. We have longer lifespans. We are healthier than ever before. We have a higher education rate than ever before. This is the best it’s ever been, but unfortunately our happiness has stayed flat from the 1950s to today.

Professor David Myers at the University of Michigan has shown that despite massive increases in our wealth, our happiness hasn’t budged at all.

The next big takeaway to share is, we know how to get there. Professor Sonja Lyubomirsky put forth an incredible model in her book, The How of Happiness, that shows that our happiness is 50 percent genetic, 10 percent circumstantial and 40 percent based on our intentional activities. Meaning the only part of that you can control is also the biggest part.

And so all of my work from the books you mentioned - The Happiness Equation, all the way up to this memoir, How to Get Back Up - entirely lives in that 40 percent. Because I believe strongly that happiness is a choice. And I believe strongly that if you do the things that research shows actually help, you will be happier. Whether that’s journaling or meditation or writing down gratitude or going for walks through the forest. We want it more than anything else, we don’t have it yet, and we know how to get it. This book, and with some of my past books, have opened up and examined the “how do we get it?” part.

CR: What are you hoping people take away from your book?

NP: I hope you get the three E’s. The first one is entertainment. I think a good book is just entertaining. You fall into it, you forget where you are. Your area 17 of your visual cortex is just clicking and you’re buzzing, and you just lose yourself. I mean that is the sign of a good book. It’s just that you disappear from whatever problems or anxieties or day you had and you’re somewhere else.

The second E is education. I really do hope that people take something from the research and the lessons and the models in the book. The sort of the end of each chapter, there is a research and model component, whether it’s about finding small ponds, or whether it’s learning how to be different because different is better than better.

The third E is empowerment. It’s funny cause this third E actually makes the other two irrelevant because ultimately what I want the reader to do is think six months from now, I don’t really remember what book it was I read, I don’t even remember who wrote it. I know nothing about it, but I just remember “Oh, that’s probably why my daughter was able to get into that college, because she put this really strange thing on a resume that nobody else would have had.” And they’re using lessons from the book in a way that is now seamless to them and is totally without any credit to me or the book because they are fully empowered.

CR: I have to say I’m getting something already just even out of this interview. Yesterday one of my daughters did not want to change out of her PJ’s. She said, “Mommy, will they think I’m weird if I’m in my pajamas?” And I should’ve just said: “Maybe, but that’s great!” If I talked to you before I would’ve said: “Yeah, wear your PJ’s because you’ll be the only one there doing it and you’ll probably be the most comfortable.” Maybe weirdness is okay.

NP: Or maybe: “I’ll wear my pajamas, too.”

CR: Even better.

NP: I mean my son and I have our toenails painted right now. Because it’s just a better way to live. And you only have 30,000 days, so make them all count.