Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

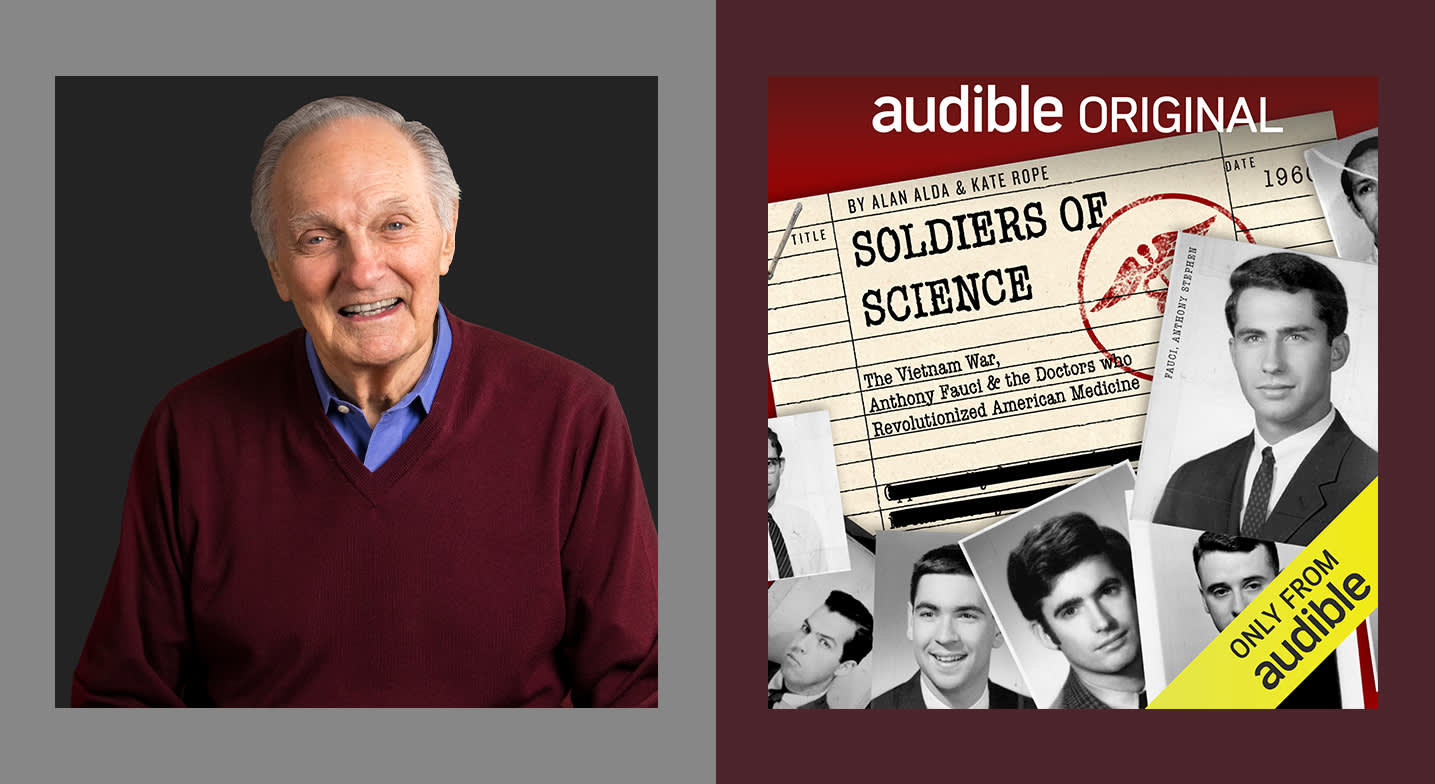

Abby West: Hi, I'm your Audible editor, Abby West. I'm excited to be here today with the legendary actor and author Alan Alda and award-winning journalist and author Kate Rope to talk about their new Audible Original documentary, Soldiers of Science, which explores a little-known Vietnam-era program that brought the very best and brightest young doctors into government service. Welcome, Alan and Kate.

Alan Alda: Hi, thank you.

Kate Rope: Thank you.

AW: Now, I had the pleasure of getting to hear some early audio from this documentary. And it's pretty fascinating, especially in the realm of things we should have known about by now. I'd love to find out from you, Alan, what drove you to this story? I know you're a writer and a passionate scientific storyteller, but what made this something that you really felt had to be out in the world?

AA: First of all, it was something that was important to the development of the health of the country and really the health of the world that was almost unknown by me, this story, and was unknown by everybody I talked to once I'd heard it. I think Kate came up with the story originally. Right, Kate, you discovered the story?

KR: I didn't discover it. It actually came to Maggie Murphy at Audible because she's neighbors with the son of one of the soldiers of science, Ari Adelson, who we interviewed. His father, Rick Adelson, served in the program. And at one point, Ari mentioned to Maggie that his father had been a "Yellow Beret," and Maggie, who has a good nose for a story, said, "What does that mean?" And that's where it started.

AA: It's such a good story. And you'd think a good story would catch the attention of the country, which we try to explore on the podcast. For some strange reason, it is pretty much unknown. When we started working on it, and we've been working on it for over a year, I would tell my friends about this amazing story that we were writing and Kate and I were writing it and I was narrating it. Nobody I spoke to had heard of it.

Kate Rope: "If you compare the number of lives they've saved against the lives that were lost in the Vietnam War, it was the silver lining of Vietnam."

And yet it changed the way medicine is researched and the way it's brought to the public. The lives that have been changed and saved by the scientists who were in this program at the National Institutes of Health, under these very unusual circumstances. That alone you would think would have brought the story to the attention of people, but it didn't. And now we have a chance to tell the story. And it's a really fascinating one.

AW: Just as you said, there's so many medical and scientific breakthroughs, Nobel Prize winners, there's such a ripple effect of impact from this program that I'm not only stunned that the world at large doesn't know about it, but that the NIH didn't really chronicle it early on. Were you stunned to find out that there wasn't a deep wellspring of information to start with?

AA: Yeah. I was a little surprised. That's one of the interesting things in the story that we tell. We go down into the basement of the NIH where the original material was found by... Kate, wasn't she an intern when she found the details of the story in the basement?

KR: Yeah, she was [Melissa Klein], a summer intern just there for a few months before she was going to go off and spend time bartending in Boulder with her boyfriend. And her father had been a soldier of science and worked at the NIH. And her whole family, her siblings had done internships there. And so it was just a matter of course that she would do it. And she happened to have a passion for Vietnam.

And so, her father said, why don’t… They just had created a history office. The NIH didn't have a history office till they were nearly 100 years old. And they just created a history office and he said, "See about an internship there." And she did. And then the woman at the head of the department, Victoria Harden, said, "Well, let me know what you're interested in."

And she said, "Well, I'm really interested in Vietnam." And she didn't even know that her father had been a part of this program until she was in college and came home from her classes, excitedly talking about Vietnam. And he said, "Oh, you know I was a Yellow Beret. I served my Vietnam War service at the NIH and that's how my career started." And she had no idea. And so she said, "Well, I'd like to look into that." And then she went down to the basement of the NIH and discovered the entire history of the program.

AA: So now I think we've whetted the listeners' appetite enough about what a good story it is in how it's unknown. Because it's probably in everybody's mind now: Well, what story? What is it? What went on there that was so important? And basically what it was, was that during the Vietnam War, all doctors were required to join military service, and it was all men at that time, everybody else... A young man graduating university, or if they were of age, they would get a number in a lottery. And there was a chance they'd be drafted and a chance they wouldn't. But all doctors had no "chance." They had to serve because they needed medical assistance at the front.

There was one exception, which was that if they were lucky enough, if they applied to the public health service, one of the things they could be accepted to, if they were really the top of their class and really smart and dedicated physicians, when they graduated medical school, they had a chance to become researchers at the NIH, to become physician scientists, physician researchers. And that was their service during the Vietnam War. And during that time... Was it roughly 2,000 people, Kate, during that time who were researchers?

KR: Over the course of the whole war, there were about 2,000.

AA: 2,000 of those people. So far nine have become Nobel Prize winners. And they changed the course of medicine in the country because many of those who didn't become Nobel Prize winners went on to be the heads of research departments in universities around the country. And what they brought with them was what they had learned at the NIH, which was these rigorous modes of research. And they had this wonderful opportunity because they were physician researchers.

They had patients at the NIH who they were taking care of with diseases that had often no etiology, no remedy. They would take care of them on one wing of this building and then walk across the hall to the research lab, where they would work on cures for the diseases of their patients, their own patients, people they cared about, people they knew and talked with every day. This was bringing the personal responsibility of the physician into the lab, where they were trained by top researchers.

And they brought that with them when they left the NIH and went to other labs. And in the process changed medicine. For instance, these are some of the people who figured out statins that have saved millions of lives. While we were working on this, Kate came up with the idea of seeing if we could get somebody to do the impossible math, as she called it. How well do you think we did with solving the impossible math, Kate?

KR: As well as we could.

AA: What's impossible is to determine how many lives were saved or will be saved in the future by these guys who were performing the military service in a hospital rather than in a foxhole.

KR: If you compare the number of lives they've saved against the lives that were lost in the Vietnam War, it was the silver lining of Vietnam. They saved so many lives, even though Vietnam was this incredible tragedy for our nation and for Southeast Asia, the silver lining of it is that from their service comes millions and millions of lives saved or improved or lengthened.

AW: True. And you not only spoke with doctors involved in the program, but also patients from the program. How challenging was it to get folks together to talk about it this far out? And potentially, I know some of this was during pandemic time, during this time in our lives.

AA: I wasn't aware of a difficulty in getting people to talk about it. I think they were very proud of the program and wanted the story told. Would you agree with that, Kate?

KR: I would. And the main patient that we tracked down, her family, they just wanted to have a chance to express gratitude for what they were able to receive, the care their family was able to receive at the NIH. And so they were eager to participate and really honor these doctors.

AA: There was one bit of reluctance, which was thoroughly understandable. And that was the term that, you've heard a couple of times as we've been talking, which is Yellow Berets. The doctors who were involved, who were accepted into this program were performing a service that turned out to be immense in its importance. And yet some people who thought that they were getting a free ride and not having to go into combat referred to them as Yellow Berets, a term of derision, based on the Green Berets who were actually over there in combat.

And this was supposed to be a term that called them cowards, referred to them as cowards. And at least one of the scientists who we asked to be on the program with us said, "Not if you're going to call it Yellow Berets or in any way indicate that that's an appropriate term." And I really agreed with him because this was such an important service they performed. And yet they were called the Yellow Berets. And we had to dig into that and discuss why that was part of the culture at the time to not... It's interesting that the story isn't understood now by many people, probably until they hear this podcast.

And at the time they didn't understand it very well. They thought, "Oh, you’re dodging the draft." That was what they were accused of. And in fact, many of them, and they tell us in the interviews that I did with them, they tell us they were ready, many of them to go to war if that was their responsibility. But here was a chance to serve in another way. Some of them, like many people in the country at that time, didn't believe in the war. And they were grateful for a chance to serve in a different way and not have to go and kill and be killed.

AW: I find it really interesting that you're mentioning that people at the time didn't understand the program and the potential benefits of the program. I'm not sure that anyone could have understood the dividends it would pay long term, but paralleling that with today, and considering that one of the more famous members of this program is Dr. Anthony Fauci, who you also spoke with, and who has become a mainstay for most Americans as we've lived through COVID-19 and understanding the scientific and rational approach to that. Have you thought about the parallels to then and now in terms of understanding the importance of science and rigorous scientific process?

AA: I have a lot. You must have thought of that too, Kate, right?

KR: Definitely. I don't think we realized when we embarked on this project, how prescient it would be at the moment that we published it. And what an important message to talk about how health and sciences is a part of national strength and keeping us healthy and strong as a country.

AA: The advances that were made were enormous and the people it produced are enormously valuable to have in our society, like Anthony Fauci. And we brought him back for a second interview when COVID hit. And I think he expressed in really vivid terms that the background he got at the NIH was very useful to him in the work he does now, and the work he's done over the years and dealing with other pandemics and outbreaks. And that was a benefit that was probably unpredictable at the time during the Vietnam War.

At that time, if you thought about the possible benefits that were going to accrue to this program, you probably wouldn't be able to look decades into the future and think, we'll be hit by an epidemic, a pandemic someday, and we'll need these highly trained people to apply what they've learned here to that. It was unpredictable.

AW: Do you think this documentary, paired with the experience that we're all going and living through now, can add to the public discourse about the importance of science and the long-term benefits to our society?

AA: I think it does. And I think it will have that effect to some extent, because it's an interesting story. There were surprises in it, and we track the path of a patient and the relationship of the doctors who treated that patient. And that makes it a very human story. We're not talking about statistics and numbers. We're not talking about pie in the sky. We're talking about things that happened to real people.

And that's an avenue in, that's a doorway to the importance of science when you make it personal like that. It was for me. I don't want to give away too much of the story, but we met with people who had been involved in this story on both sides of the doctor–patient relationship. And it was very moving.

KR: We open the podcast with the story of a mother who is desperate to save her daughter. And we follow her story throughout the podcast and in so doing, we also meet all the soldiers of science along the way. But she grounds us in the fact that this science at its base is about human beings and keeping them well when we're talking about the public health. And so it's very touching because the people in this program were researchers and they were doing cutting-edge things with electron microscopes and the age of microbiology was coming online. But they were all very connected to patients. They were all guys who had gone into med school to be doctors. And they never lost that.

Kate Rope: "...Health and sciences is a part of national strength and keeping us healthy and strong as a country."

And that enabled them to make some incredible breakthroughs and to really stick with trying to figure out what was wrong with a patient and have, in the case of some of our doctors, stick to one question for 10-plus years in the lab, through failures until they finally got a breakthrough. I think it's a nice pairing of the perseverance and the humanity of patients going through this process. And then the humanity of the doctors who see their patients, and then as Alan said, go into their labs and work like hell to find an answer because they care. And because they've been given a really fertile environment in which to go look for answers.

AA: And even after they left the NIH, when their time there was up, the war was over, or for whatever reason, they were going out to establish other labs. They went to those labs still trying to solve the problems that they had encountered with their patients, with the diseases their patients had. And work sometimes went on for years and years later, but still fueled by what they had learned at the NIH.

AW: Those parts where you're speaking to patients about the patient care and about the sometimes painful memories that they have, I found it really moving and I'm going to say a little comforting to hear you in those moments, being very compassionate. As well as, we have to stare at the elephant in the room, which is that your voice is so recognizable and so well known, and creates a comfort space, starting from your time on M*A*S*H on forward and how people know you and trust your voice, so in those moments. And you've had a really varied career—you nodded to your scientific bent before, but what would you say has helped you prepare to tell this story and to be the person bringing this story to light?

AA: That's an interesting question. And thank you, I've never been the elephant in the room before. That's a new one for me.

AW: You're welcome.

AA: I think what prepared me is a lifetime of what I've been doing. Starting with acting and then learning improvisation. And then applying those skills that I learned in those two areas, applying them to interviewing hundreds of scientists on the science program on PBS called Scientific American Frontiers and a couple of other miniseries on science that we did. And that, combined with my curiosity, I really have genuine curiosity about these things. I don't do it as a job. I do it to educate myself and it's really a great education. I'm having a wonderful time and I have for decades now.

Talking to these really smart people who are devoting their lives to making our lives better. And it's fun for them. And it's fun to listen to them enjoy the search that they're on to find solutions, to find understanding, to get knowledge about the way that the universe works. So my contribution is to get comfortable with them in an improvisational way. And I don't come in, it might've driven Kate a little crazy, because I don't come into an interview with a list of questions usually. I come in with curiosity and whatever they say in answer to my curious question becomes the foundation of the next question.

I don't ask the next question because it's on a piece of paper. I ask you because I truly want to follow that path that they've just opened a door to. And that changes them and it changes me. It makes it a more lively thing that's happening. It's not just fill in the blank here and then I'll go on to the next blank. You can fill that in. It's a different kind of thing. It's not really an interview. It's more of a conversation. So because we had to get certain facts established. I had to depart from that a little bit and I did have questions in front of me.

And I know Kate was in the control room and would come in at the end and start saying, you didn't ask this, you didn't ask that. Which was very helpful because we had to get that information out. But that's what I had to contribute and it comes from my curiosity, and what I've learned as an actor. I could combine those two things and get stuff out of them that we might not have gotten otherwise.

AW: I'd say that active listening skills, that comes in handy often.

AA: It really does.

AW: In that vein of following just my own curiosity, I don't have necessarily a question here, it is just wondering if it sat with you—I was struck by, I don't remember if it was Dr. [Harold] Varmus or Dr. Fauci who acknowledged the place that privilege had in their being able to be in this program, whether it was racial, gender, or socioeconomic privilege that allowed them to be in the doctor draft program. And I found it really interesting. I didn't know if that was coming from a present looking-back space of understanding. But just how that plays into how we look at science in our society today and access and things like that. I just found it really interesting that that was even brought up in this moment.

AA: Yeah. I don't remember who brought up the notion of the privilege that they enjoyed. And they enjoyed a privilege that was not enjoyed by women at the time because only men were draftable and therefore eligible for this program. And there was such a dearth of people of color in medical school. So they wouldn't be privileged in the same way either. That might even have been a time… I don't know it might've been some schools that even had a quota for Jews. I'm not sure.

Alan Alda: "One of the things I felt in talking to every one of the physicians was that they were dedicated to helping people live better lives."

KR: I think that the story has layers of privilege and the person who brought it up on the tape that I think you're referring to was Harold Varmus. He was speaking about it in the context of the Vietnam War, because that was very much a conversation back then about privilege, who had access to get deferments, you know, college kids. And so there was this socioeconomic component to who ended up serving in Vietnam because they didn't have the outs that people who had greater connections did. For him, that was why the war was repugnant in many ways. He didn't believe in the cause of the war, but he also was very turned off by the way in which we were getting people to fight in the war. And that was part of the reason he didn't want a part of it.

So he spoke to that. But then to your point, now looking back in this moment, we can say, well, how many women were even in med school in the '60s? Almost none. They weren't really welcomed until the '70s. And then additionally, there was Melissa Klein, the intern who unearthed the documents of this program, who spoke with several women. She spoke with several couples in which the woman was actually more qualified for the position than her husband was. And [the woman] said, "Oh, well, it was just understood that these spots were going to be saved for men because they were facing the draft or they were facing going, not necessarily fighting, but being medics in the Far East."

And then you have the fact that there aren't Black and Brown doctor people in med school and then having access to this. But that was who was heavily serving in Vietnam. So it's just interesting, all the different layers of privilege, and it’s important to look at. When you think about it, this did create a legacy for science. This seated the university research system that we have now. But one of the people we talked with, who's an economist at MIT who looks at innovation and science, he said, "Let's not forget that the benefits that these people had access to will now filter down to another generation that is more diverse."

So the things they were taught, the styles of research, the collaboration, will influence a much broader-looking body of scientific researchers. But we felt it was an important thing to talk about because it was a topic that was important during Vietnam. And it's obviously an extremely important topic now.

AW: I love that. As we close out here, I want to ask, having spent a year or more, more than a year honestly, digging into this and getting to know these stories, Kate, Alan, what is your biggest takeaway from this project? What is it that's sitting and staying with you as we move on and the world gets to hear it?

AA: Kate, I'll let you go first. Go ahead.

KR: I think what sits with me more than anything is the incredible orientation towards service of all the people we spoke with. These are incredibly smart people and all the things they are doing are for the betterment of humankind and the world. And really, that is their driving motivation. It's not money. You know, many of them stayed in government service where you're not going to be raking in the dollars. They're passionate about research and they're passionate about people. And those two things, when you bring them together, can lead to these amazing lifesaving breakthroughs. So I will forever be honored to have been in the room with these people.

AA: I had a similar feeling, and I was thinking about what Kate was saying about their sense of service. One of the things I felt in talking to every one of the physicians was that they were dedicated to helping people live better lives to even just live when they were attacked by a disease that had no known remedy at that time. But that sense of service extended beyond the work they did there. Several of them said they wished there were a way to replicate that program now.

There still is a program, I believe at the NIH, of associate researchers, which is similar to what this program was. But there's an element missing, which is that you don't have a choice between this and going to war and there's no draft. And what several of the physicians that we interviewed said was, "Wouldn't it be great if everybody had to do a couple of years of service to the country and that this was one of the ways they could serve if they were qualified?"

But to do service that helps the country is a notion that we don’t have as part of our regular way of looking at this society. And if we took it for granted that you had to serve one way or another, the kind of results that these men accomplished, came up with during the few years they were at the NIH, could be multiplied in so many other areas. And that's what they were suggesting, because they knew how powerful it was in their area of expertise.

AW: I am heartened that that's what you both took away from it because that's definitely my biggest takeaway, both having listened to the Fauci interview that we snuck out into the world last summer, that came out of your conversations and research here and listening to this entire Soldiers of Science. Because that is sort of a do-gooder mentality with no snark, all earnestness, and all sincerity and understanding of the greater good and impact. So, I'm grateful that everyone else is going to get to hear this as well. Thank you to both of you for putting in that time and doing us that service.

AA: Thank you. That was fun talking with you. Thanks, Abby.

KR: Thank you, Abby. I want people to see the goodness that is behind the science that is being put out into the world. The thoughtfulness, the incredible positive intention, and the care with which these people do their work in order to make our lives better. And so that everybody can learn to trust them as much as I do and do even more after having spent time with them.

AW: Thank you. This has been delightful. As someone who spent some of her newspaper reporter days dealing with health and science, this has been really great. Thank you.

AA: Thank you. That was fun.

KR: Thank you, Abby. Yeah, it was fun.